By George Friedman

The meetings between Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Donald Trump are underway. Given Trump’s position during the presidential campaign, the expectation was that the sole conversation would be about trade relations. Perhaps some attention would be paid to the South China Sea. But given recent events, the likelihood is that a great deal of time is being spent on North Korea.

As we have discussed, the North Koreans have not quite crossed the red line on possessing nuclear weapons. But they appear to be lurking close to that line, and even flaunting it. The recent launch of four medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) demonstrated that North Korea now has a fairly reliable medium-range missile. Other indicators, including photos, show it might have a sufficiently miniaturized nuclear weapon to marry to a missile.

Until now, the existence of a North Korean nuclear weapon was simply an idea. It was a program, not a reality. Of late, we have moved from an idea to a real possibility. With all of these elements, U.S. intelligence may know the precise state of North Korea’s program. The U.S. president must calculate this question: Is the intelligence estimate he receives – assuming it says the threat is not yet real – correct? And if the estimate is wrong, would North Korea use the weapon? The closer the North Koreans get to a nuclear weapon, the less uncertainty is acceptable, and the more the president must assume the worst. In the ambiguous space between a program and reality, it may be hard to tell when the line is crossed. Once the line is crossed, the North Koreans may act. We don’t know that they will, but we also don’t know that they won’t.

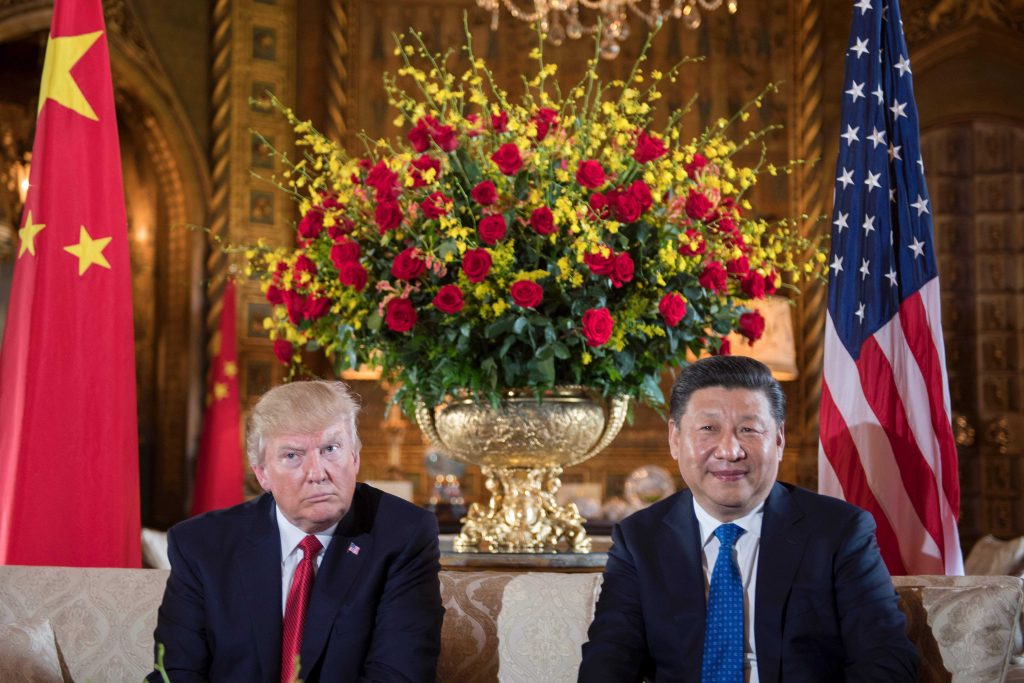

U.S. President Donald Trump, left, sits with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a bilateral meeting at the Mar-a-Lago estate in West Palm Beach, Florida, on April 6, 2017. JIM WATSON/AFP/Getty Images

Given the stakes, the uncertainties will likely force the assumption of the worst. And assuming the worst requires action. I don’t know what the military recommends as pre-emptive action, but my assumption is that the North Koreans have hardened sites that conventional weapons and special operations teams can’t pierce – at least not with high certainty of success. Therefore, if we tilt all the uncertainties to the worst case, then a nuclear strike might be needed to take out the threat.

The United States is the only country in the world to have used atomic bombs. The U.S. is not eager to reintroduce them. Whatever the U.S. claims about North Korea’s capability, it will be dismissed by our adversaries and used as evidence of U.S. recklessness. This is, I suspect, why Trump urged the Japanese to develop nuclear weapons. If the strike has to be launched, the United States does not want to do it alone. And Japan – one of the most technically sophisticated countries with an extensive range of commercial nuclear reactors in place – undoubtedly has developed weapons capability to some extent.

The U.S. does not want to strike North Korea. Therefore, Plan A is to ask the Chinese to intervene with the North Koreans. It is extremely interesting to me that North Korea has chosen this time to put its developing capabilities on display. Obviously, there might be internal reasons, or they are simply proceeding as planned. However, I have noticed an imperfect model in place. On some occasions, when the U.S. is pressing China particularly hard on trade and related issues, North Korea goes out of its way to focus attention on itself, increase concern in the United States about its intent, and force the U.S. to ask the Chinese for help in managing North Korea. If North Korea wants to develop nuclear weapons without an American response, it would be in its best interest to increase, not decrease, American complacency. Yet the opposite happens – it increases U.S. concerns through deliberate, highly visible actions. In doing so, North Korea increases the risk of a U.S. strike taking out its nuclear capabilities.

The North Koreans talk crazy, but act deliberately and cautiously. They survived the collapse of the Soviet Union, their patron, precisely because of this caution. However, their nuclear program, which ought to be as understated as possible, periodically creates a situation where the threat to North Korea increases.

Normally, Beijing’s position is that it has poor relations with North Korea and will find it hard to influence it. Invariably, despite the difficulties, China manages to defuse the situation. At that point, when the U.S. turns to a discussion of trade issues, China has already done an enormous service at great effort and cost. China can then argue that it is continually bailing out the United States, and a reasonable compromise – given its service to the U.S. on a major issue – would be to provide some breathing room on other issues. It’s the least the U.S. could do.

I am bluntly raising the possibility that the Chinese and North Koreans are playing good cop, bad cop. The North Koreans create a crisis frequently built around their nuclear weapons, while China uses that crisis to deflect U.S. pressure on trade issues. There are, of course, arguments against this theory. China may not have the influence on North Korea that I claim. Too many instances have occurred where trade pressures do not generate a North Korean demonstration.

But I am forced to wonder why North Korea would risk forcing a U.S. pre-emptive strike by displaying its growing capabilities as blatantly as possible. Perhaps the North Koreans aren’t close to a weapon, U.S. intelligence knows this, and the North Koreans know the U.S. knows. Perhaps their status actually has no ambiguity, and therefore, no risk.

But I will note that China was about to meet the mother of all trade pressure – Donald Trump. And Xi was apparently confident that he could resist. All things considered, he shouldn’t have been. The buyer is in a stronger position to dictate new terms than the seller. Nevertheless, Xi came, the MRBMs were launched, and the alarm was palpable in the Trump administration. The meetings began with the Americans asking for a favor and the Chinese willing to spend their precious currency in North Korea to help the U.S.

It could be coincidence, but it is a very useful coincidence for China.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East