By Jacob L. Shapiro

U.S. President Donald Trump told Bloomberg on Monday that he would meet with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un “under the right circumstances.” Trump was criticized over the weekend for inviting Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte to the White House. The New York Times reported that Trump extended the invitation without the prior knowledge of the State Department and the National Security Council. Last month, Trump met with Chinese President Xi Jinping and offered undefined concessions on trade for China’s assistance on the North Korea issue. In two weeks, Trump will receive a visit from Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan – another illiberal leader of a country with which the U.S. has had uneven relations.

The media is busy making a caricature out of Trump on the North Korea issue. Trump’s comment from the campaign trail about meeting with Kim over hamburgers in a conference room is making the rounds again. Human rights groups and Senate Democrats are bemoaning the Duterte invitation with self-righteous indignation, claiming that Trump is essentially sanctioning human rights abuses in the Philippines. On the Trump-Xi meeting, the media chose to focus less on the results of the summit than on Trump’s flip-flop on a major campaign position – as well as his fondness for Mar-a-Lago’s chocolate cake. Trump has also been criticized for congratulating Erdoğan on winning a referendum on constitutional reforms two weeks ago, and the volume of the criticism will rise as Erdoğan’s visit gets closer.

U.S. President Donald Trump (left) pumps his fist as he and Chinese President Xi Jinping walk together at the Mar-a-Lago estate in West Palm Beach, Florida, on April 7, 2017. JIM WATSON/AFP/Getty Images

There is a common thread to all of Trump’s maneuvers, and it is not the thread to which the media and Trump’s opposition from both sides of the aisle are holding fast. Trump is using American power to pursue a diplomatic course of action in realizing U.S. strategic imperatives. When Trump took office, the fear was that he was going to be a warmonger whose lack of experience would manifest in rash decisions leading to military conflict. Trump’s presidency is still young, but China is an example of how far off this expectation has been thus far. Many expected a trade war – or even a real war – between the two countries following Trump’s rhetoric on China and his acceptance of a phone call from the Taiwanese president. But China and the U.S. have a cooperative relationship, and it is certainly no worse now than it was under President Barack Obama’s administration.

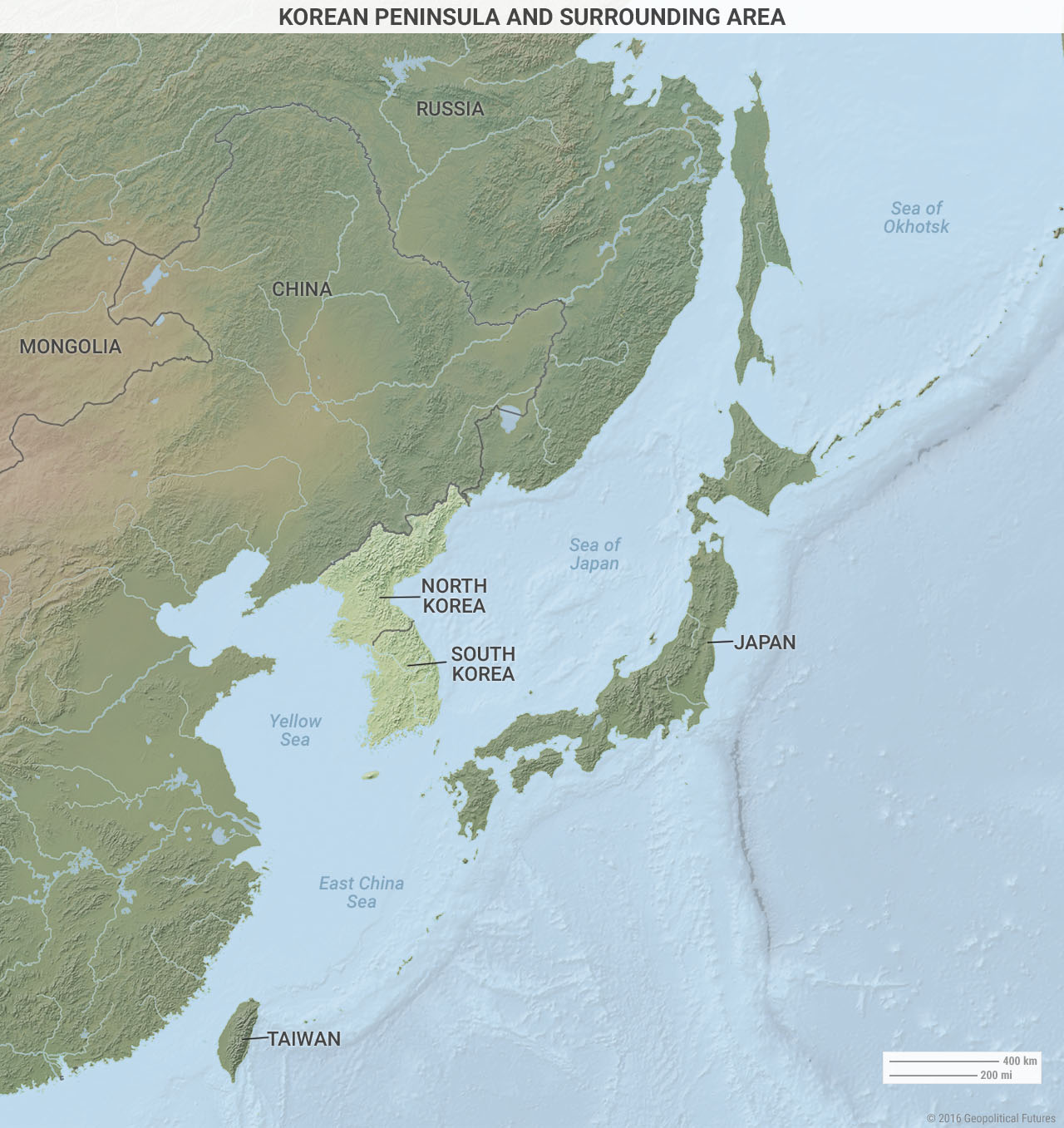

Consider each of these moves in isolation, and ignore the tweets and the bombastic way in which Trump likes to make his points. With North Korea, the U.S. has an interest in preventing Pyongyang from developing deliverable nuclear weapons. This is a red line issue for the United States. North Korea wants to ensure its regime can survive. It is developing nuclear weapons because it fears the U.S. or China will attempt to destroy the regime. The U.S. would prefer not to have to attack North Korea because the results would be disastrous and the U.S.’ ability to knock out North Korea’s nuclear weapons program is still an open question.

By offering to meet with Kim, Trump is presenting the supreme leader with a way out of his dilemma. Kim can portray himself as having forced the mighty capitalist United States into a face-to-face meeting. For Trump, it is a low-cost, high-reward move. The U.S. would have to assure North Korea that the U.S. will not take out the regime if Pyongyang stops developing nuclear weapons. There is no assurance that Kim will take this deal or that either side could trust any assurances given. But Trump can point out that the U.S. is going to destroy the nuclear weapons program one way or another; Kim can either benefit from doing it himself or lose face by being forced to do it by the U.S. The worst-case scenario here is that nothing changes and the U.S. does what it must. The best-case scenario is that the U.S. leverages the threat of force with a diplomatic gesture and enough private assurance to encourage North Korea to change its behavior.

The Philippines is another country where the United States faces a strategic challenge that has been bedeviling U.S. policymakers. The Philippines has been a key part of U.S. strategy in the Pacific since 1898, when the U.S. took possession of the Philippines from Spain. Duterte is a seemingly mercurial man who is willing to court support from other countries, most significantly China. In the last five days, the Philippines released a statement after an Association of Southeast Asian Nations conference that ignored territorial disputes with China, welcomed three Chinese ships for a port call at Davao City, and indicated that it would welcome joint Chinese-Philippine military drills. Meanwhile, Duterte’s response to Trump’s invitation was nonchalant: He said he’d have to check his schedule and see if he could pencil in the U.S. executive.

China is making a play for the Philippines, and ignoring Duterte or assailing him for his record on human rights is not going to keep the Philippines away from China. Duterte was democratically elected and he continues to enjoy overwhelming popular support in his country. In the past and present, the U.S. has dealt with regimes and leaders who have done far worse than call the U.S. president names or violently crack down on domestic drug problems. The Philippines is a critical part of the U.S. alliance structure that aims to box in China in the South China Sea. The Philippines would be critical to China if it could use Duterte to turn the Philippines into, if not an ally, at least a neutral party.

The trick here is that the Philippines also needs the U.S. Duterte does not want to give up on Philippine territorial claims, nor does he want his country to trade one overlord 7,000 miles away for another one that is closer and has more aggressive designs on Philippine territory. By inviting Duterte to the White House, Trump is signaling that the Philippines is important. He is offering Duterte an important symbolic victory he can tout at home in Manila. With the diplomatic foreplay out of the way, the U.S. can establish what the Philippines wants and needs out of the relationship and come to an arrangement so that the Philippines remains firmly in the U.S. camp. The U.S. and the Philippines share interests, and formalizing an understanding of those interests means the U.S. can keep China too weak to challenge U.S. military supremacy in the region anytime soon.

The story is similar with the U.S. approach to both China and Turkey. When it comes to China, Trump took extreme positions going into a meeting with Xi. He emerged from the meeting with an understanding about China helping the U.S. on North Korea in return for trade considerations. China’s level of power over North Korea remains to be seen. But Trump is attempting to use a source of leverage – Chinese dependence on exporting to the United States – to extract an important concession that would decrease the chances of a costly war in North Korea. On Turkey, Trump calculated that making an issue out of a democratic referendum on constitutional reforms was less important than engendering goodwill between the U.S. and Turkey. The U.S. needs Turkey’s help to expel the Islamic State from its home turf in Raqqa. Here, U.S. leverage is shakier than in the other cases. But the end goal will be to use American power to convince Turkey to put some real skin in the fight against IS so that the U.S. doesn’t get trapped in yet another conflict in the Middle East.

One of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s former aides once told a story that has become a famous anecdote about the limits of American presidential power. After a meeting about the Vietnam War, Johnson leaned back in his chair and said, “If I could just get to the table with Ho Chi Minh, we could find a way out of this damnable war.” Johnson was a master of domestic political power and had spent a lifetime developing leverage in U.S. politics. But even if he had been in a room with Ho Chi Minh, he would have had nothing to offer. He had no leverage. Johnson could not have grabbed Ho Chi Minh by the lapels, given him what Robert Caro refers to as “the Johnson treatment” and ended the Vietnam War with a snap of his fingers. The two countries’ interests were diametrically opposed. The North Vietnamese were dug in for a fight, and for the U.S., the Cold War hung in the balance.

Trump is similar to Johnson in the sense that the effectiveness of his recent moves toward the Philippines, China, North Korea and Turkey has nothing to do with Trump’s personality. He can’t, for instance, forcefully shake the North Korean leader’s hand, offer him a cheeseburger and then convince Kim to end North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. But unlike Johnson, Trump is not (yet) dealing with intractable enemies. North Korea wants regime survival. The Philippines wants its territorial claims respected and its internal politics ignored. China wants access to the U.S. market. Turkey wants to tie the war against IS to its Kurdish problem. These are all separate issues, but each country has room to compromise. The diplomatic overtures may not work in the end, but the U.S. gains nothing by not reaching out to foreign leaders it doesn’t like.

Diplomacy is not about cultural exchange nights at embassies or dialogue between countries that see eye to eye. Diplomacy is about the use of leverage in the form of political and economic power to compel another country to change its behavior. It can also involve two sides coming to a mutually beneficial compromise. Trump is using U.S. power to try and achieve U.S. strategic goals via diplomacy and not military conflict. His style is unorthodox and at times objectionable. But style is a small price to pay if it means getting North Korea to back away from a deliverable nuclear weapon or preventing the Philippines from drifting too far into China’s orbit without having to use military force.