By Jacob L. Shapiro

U.S. President Donald Trump told Chinese President Xi Jinping that he accepts the “one China” policy during a phone call on Feb 10. It is ironic that in the age of social media, the United States has entered a period of telephone diplomacy. Every word the U.S. president says over the phone seems to generate headlines. The headlines over Trump’s embrace of “one China” have been histrionic: Trump has given China “the upper hand,” Trump is nothing but a “paper tiger,” Trump has lost credibility in Beijing. Just two months ago, everyone was focused on the congratulatory phone call Taiwan’s president made to the then president-elect. The headlines at the time were equally melodramatic. They portrayed Trump as either a bumbling novice who clearly didn’t know what he was doing or a brilliant tactician setting China back on its heels.

“One China” is a pleasant fiction. It is a vestigial diplomatic arrangement whereby China gets official recognition from most of the world and the U.S. recognizes Taiwan as an unofficial ally. In December, Trump indicated that the U.S. was not locked into an inevitable acceptance of the “one China.” This was a tactical move that had a specific purpose: to put China on notice that the U.S.’ previous policy was not sacred by dint of being the way things were done before. The real news isn’t that the U.S. has capitulated and accepted “one China.” It is that the U.S. does not view “one China” as a foregone conclusion and has reserved the right to take it off the table if the situation dictates.

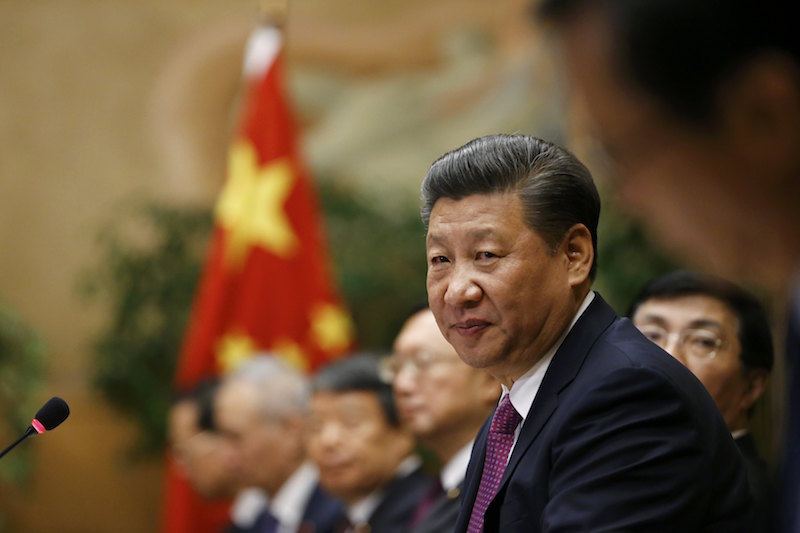

Chinese President Xi Jinping looks on during a meeting at the United Nations European headquarters in Geneva, on Jan. 18, 2017. DENIS BALIBOUSE/AFP/Getty Images

With this diplomatic foreplay concluded, the U.S. and China can now get down to addressing the issues currently dividing the two countries. These issues can be divided roughly into three main areas. The first is U.S. disapproval of Chinese military activity in the South and East China seas. The second is the U.S. desire to change some of the parameters of the U.S.-China trade relationship. The third is what to do about North Korea, which carried out its first missile test since Trump took office the day after the phone call with Xi.

With regards to the first issue, the U.S. is unhappy with the current level of Chinese assertiveness in the South and East China seas. China is building up military installations on various shoals and islands that are also claimed by other countries in the region. China likes to send its ships to controversial places, such as the waters around the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. These ships rarely take offensive action and usually withdraw. The result is an expression of diplomatic outrage from whichever country believes its claims or waters have been violated. In recent months, China also has taken to sending its overhyped and newly operational aircraft carrier into politically controversial areas, such as the Taiwan Strait.

The problem for the U.S. in dealing with this issue is that China’s moves are more publicity stunts than challenges to the balance of power in the region. The various islands China is building on are small enough that strategically significant supplies of weapons or ammunition can’t be stationed there. The U.S. and other countries find it annoying when China sails ships into contested waters, even sometimes into the sovereign waters of another country. However, China does not use these ships to obstruct global shipping lanes or attack U.S. naval assets. The worst that happens is minor scuffles over fishing rights. The point is that while the U.S. does not like these moves, the political and military costs of stopping them are too high.

The second issue is the U.S.-China trade relationship, which is as complex as it is large. It is well established that China needs access to the U.S. market for its exports. It is also well established that U.S. consumers depend on access to cheap imports from China. What the U.S. objects to is China’s currency manipulation and reduction of its export prices to such an extent that American producers cannot compete. Trump made this a key plank in his campaign, but it is not a new issue. Under former President Barack Obama, the U.S. raised tariffs on some Chinese goods, applied anti-dumping duties on others and brought many cases to the World Trade Organization over Chinese non-compliance with trading rules.

There is a great deal of concern that a trade war is brewing between China and the U.S. That is hot air, and the air is only going to get hotter. Trump promised his base that he would be tough on China. He told these constituents they would reap the economic benefits of this toughness in the form of new jobs. That is going to be an impossible pledge for Trump to uphold. Even if it were as simple as finding the right economic levers to stop U.S. jobs from moving to China, the jobs that have already left would not simply return to the United States. This means Trump will be under significant pressure to demonstrate that he is extracting economic concessions from China. Ultimately, the economic relationship between the U.S. and China is too important for either side to turn its back on. There will be friction, accusations and recriminations, but trade will go on.

The last issue is North Korea. On the campaign trail, Trump accused China of not doing enough to combat the North Korean threat. For China, North Korea is a valuable tool for managing its relationship with the U.S. The more the U.S. must rely on China to manage North Korea, the more leverage China has over the United States. That said, the main goal for Washington and Beijing relating to North Korea is not in dispute. The U.S. does not want North Korea to have nuclear weapons. Neither does China. The disagreement comes in how to achieve that goal.

The Obama administration made a point of highlighting North Korea as the top national security threat the U.S. would face in the coming years. This is an exaggeration. North Korea does not have a device capable of reaching the United States. If it develops one, North Korea won’t fire it at the U.S. Mutually assured destruction loses nothing in its translation to Korean. North Korea’s key goal is regime survival. Its nuclear program is about ensuring that survival. The irony of nuclear weapons is that they only ensure survival by not being used.

Besides this, the U.S. lacks the ability to destroy North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. A military intervention would have to be a surgical strike against North Korea’s nuclear infrastructure and current weapons stockpiles. The strike itself is theoretically possible. The problem is the incredibly precise intelligence needed to turn theory into practice. Furthermore, such a strike would have significant fallout. At best, its ramifications would be limited to reinvigorating the current regime’s legitimacy. At worst, North Korea might retaliate with attacks against South Korea and Japan that would kill many people. Sanctions are another approach pushed by the U.S. Sanctions, however, have had a limited effect on North Korea’s leadership as well as on other regimes. Iran, for example, agreed to a deal on its nuclear program because the rise of the Islamic State changed the strategic situation for both Washington and Tehran. Sanctions hurt the Iranian economy but new shared interests are what brought both sides to the negotiating table. Sanctions on Russia have not resulted (and won’t result) in an end to the Ukrainian conflict either.

China does not need to be told North Korea is an issue. China does not have the luxury of the entire Pacific Ocean separating it from what happens north of the Yalu River. China does not want North Korea to have nuclear weapons. More than that, China wants a certain degree of, if not political stability, than at least predictability in North Korea. If the North Korean regime collapses, the effects will spill over into China, and the prospect of unification on the Korean Peninsula will present a serious long-term challenge to Chinese interests. For all these reasons, China argues against antagonizing the regime in Pyongyang. Such moves from China’s perspective only cause North Korea to double down on its current approach and further destabilize the situation. China prefers a long, patient approach that maximizes regime stability and Chinese influence.

These three issues will define the relationship between the U.S. and China during Trump’s presidency. Whether it is appropriate to refer to Taiwan as the “Republic of China” will be determined by the geopolitics of the U.S.-China relationship, not vice versa. China has carefully crafted an image of being both incredibly sensitive when it comes to diplomatic protocol and deeply skilled in the art of negotiation. What can be said at least is that China is exceptionally good at crafting that image.