By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Feb. 17, Chinese President Xi Jinping presided over a seminar on national security in Beijing. Xi identified three processes that from China’s perspective define geopolitics in 2017: “multi-polarization of the world, the globalization of the economy and the democratization of international relations.” Xi said these processes present challenges and opportunities for China, but China’s response is the same no matter what happens. “We must maintain our strategic steadiness, strategic confidence and strategic patience,” he said. Those are impressive words, but politicians say impressive-sounding things all the time at such events. The important thing to understand is what foreign threats China faces to its national security irrespective of the way Xi described them.

Multi-polarization of the world is a fancy way of arguing that no single power dominates. In this view, many significant world powers exist, some rising and some falling, and parity between nation-states in terms of economic, military and political power is developing. As China looks at the world it sees a changing of the guard. Russia is weak, and its economy is in tailspin. The European Union has lost cohesiveness, and individual nation-states are re-emerging in importance on the Continent. The United States just went through one of the most contentious electoral cycles in its history and remains bogged down in Middle East wars it cannot win. The future belongs as much to China as to the United States, according to this view.

Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a speech during a high-level event at Assembly Hall in the United Nations European Headquarters in Geneva, on Jan. 18, 2017. DENIS BALIBOUSE/AFP/Getty Images

The globalization of the economy is the basis on which China has dramatically increased its power in the last 30 years. China has grown at an astronomical rate during this period, following in Japan’s footsteps and having reached the point to where it is the world’s second largest economy in terms of GDP. China accomplished this by using its vast population to produce a range of goods more cheaply than they could be produced in other countries. Whether furniture or electronics, China became a producer of a range of manufactured goods and enriched itself greatly in the process. Growth is now slowing, and China still has hundreds of millions of people in the interior who have not been enriched. Beijing wants access to markets to encourage growth.

The idea of democratization of international relations alludes indirectly to the period of Western imperialism in the 19th and 20th centuries, from which China greatly suffered. A few key Western powers dominated most of the known world, and China was one of many countries that were dominated and exploited by this exclusive world order. The rules of the international system – the United Nations, the World Trade Organization and other international organizations – were created to keep the interest of what remained of these powers in place after World War II. Democratization of international relations means challenging those institutions and replacing them either with new ones or bilateral understandings. When China says it does not recognize the jurisdiction of an arbitration court in The Hague over territorial claims in the South China Sea, it is fighting to “democratize international relations.”

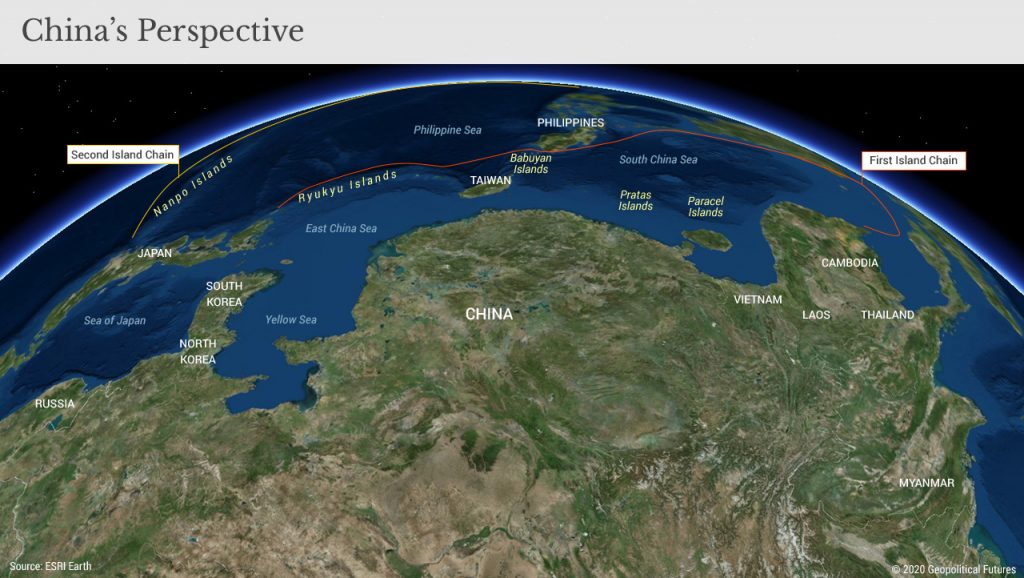

There are now three processes shaping global geopolitics. They are an esoteric way of describing the three biggest challenges to China’s national security: the dominance of U.S. power, the backlash against globalization at precisely the moment China’s economy is buckling, and the limited influence of China’s political power because of these realities. The first challenge is that the world is not multipolar. It is unipolar, and the United States is the pole. China has vastly increased its economic, military and political power, but it is still not competing at the same level as the United States. China’s goal is not to overcome the U.S.; China’s leaders know this is not possible in any reasonable amount of time. China instead is trying to increase its power incrementally, slowly reaching a point where it is at least on a level playing field with the United States.

The second challenge is that there is a global backlash brewing against globalization. The United States is not the only country that has problems with China’s trade practices. The EU has its own problems and lawsuits against China as well. China has been cutting prices on exports and dumping excess commodities into the market for years, and countries affected by these practices are not able to let businessmen profit from globalization while workers and lower classes at home lose jobs and face economic hardship. The issue is not whether these jobs can be brought back – they probably can’t. The problem is that it has become politically untenable in many countries to continue business as usual with a globalized economic system that has left many behind and enriched a relatively small number immensely. Politics demand some kind of change, and any change that restricts Chinese access to global markets is a national security threat.

As for the democratization of international relations, there is only so much China can do. China has invested significant money in infrastructure projects throughout Asia including the Asian Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Many countries happily accept this money. Money, however, is not synonymous with power. The scale of China’s projects still pales in comparison to most international institutions today. Many countries in Asia are suspicious of China’s moves and have common interests in blocking Chinese territorial ambitions. Old institutions like NATO and the EU may obsolesce, but new alliance structures will arise in their place, some likely designed to contain Chinese ambitions. This is a long game that China is playing, one that requires many decades and changes in power balances to come to fruition.

Xi’s description of how China should respond is also somewhat veiled but very revealing when one ignores the words and sees how these challenges put pressure on China’s president. Steadiness means Xi needs to solidify his power base ahead of this year’s Communist Party Congress (CPC) so that he can control discontent and attempt to enforce reforms in China’s economy. Confidence means the CPC must present China as a global power as a way of increasing Chinese pride in the regime without getting into a fight it can’t win. It is like school, when a boy who cannot win a fight against the bigger kids spreads rumors about how strong and good at fighting he is so they won’t attack him. It works great as long as no one has an incentive to try their luck. And patience means that responding to these challenges will take a great deal of time.

China faces an uncertain period with many strategic challenges it must overcome. The world’s global power does not see eye-to-eye with China on many issues. There is significant global political backlash to the economic system that has allowed China to develop at the rate it has. China’s influence is limited, but it must try to cultivate it especially in its immediate vicinity. These are the national security challenges Xi is facing, even if he did not say so in so many words.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President