By Jacob L. Shapiro

Power is a relative concept. To say that one state is powerful means nothing. Power only derives meaning if it is evaluated in comparison. Two of the states whose powers we constantly re-evaluate are Russia and the United States. Much of our analysis is driven by just how weak we believe the Russian Federation is. When we look at its moves in Syria or Eastern Europe, we keep in mind Russia’s relative strengths and weaknesses compared to its neighbors and the United States. There are many different ways to evaluate this discrepancy, but comparing the regional economies of the U.S. and Russia is particularly striking.

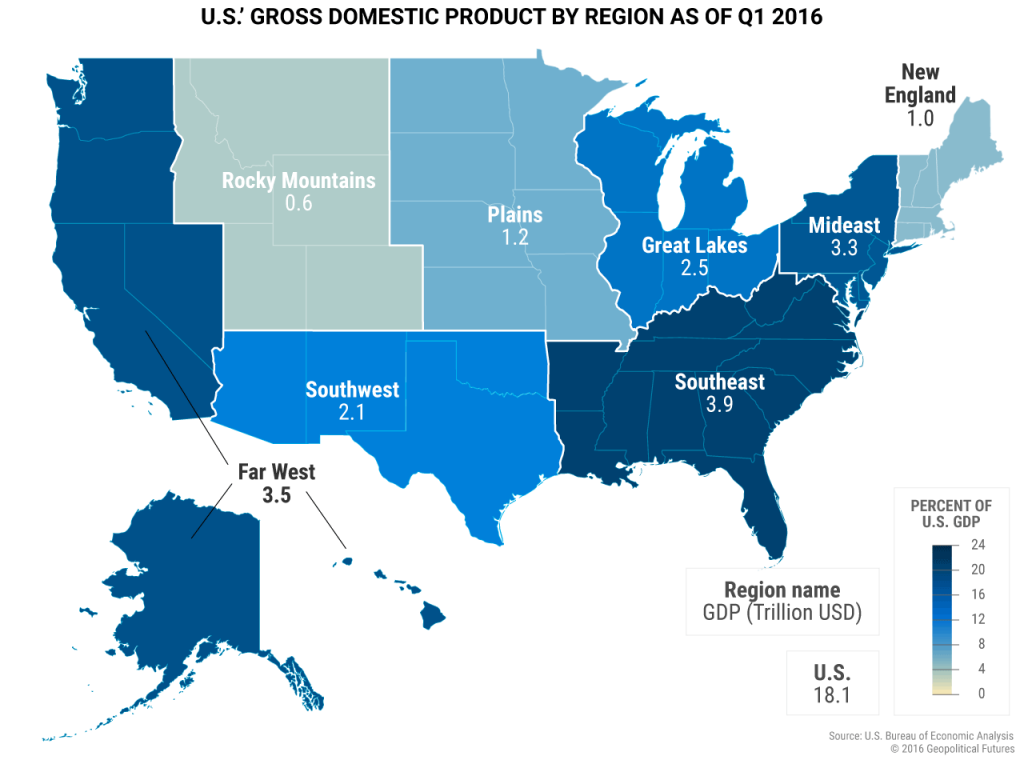

The first element of this analysis must be to recognize how much larger the U.S. economy is than the Russian economy. Russia is the largest country in the world in terms of area – almost 11 percent of the world’s landmass is sovereign Russian territory – but Russia’s economy pales in comparison to the U.S.’ According to 2016 first-quarter figures from the U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. GDP is around $18.1 trillion. Russia’s economy is roughly a tenth the size of the U.S.’ (the World Bank stated that Russia’s GDP in 2015 was $1.3 trillion.) According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, U.S. military expenditures in 2015 were 3.3 percent of GDP, and Russia’s were 5 percent of its GDP. That still puts Russia among the top five military spenders in the world, but in absolute terms it means Russia’s military expenditures add up to roughly 10 percent of U.S. military spending.

One of the results of Russia’s physical size is a highly regionalized economy, as the map above shows. Russia is a federation, or a collection of 85 different federal subjects that range in structure from autonomous regions and republics to individual cities. But for bureaucratic and governing purposes, Russia divides these 85 regions into nine larger districts. The above map shows what percentage of the economy each of Russia’s disparate regions contributes. The figures are noteworthy. According to the latest available data from the Federal State Statistical Service, the Central Federal District accounts for 35 percent of the entire Russian economy. Located in this district, Moscow alone accounts for 21.7 percent of the entire Russian economy. That means that Russia’s capital city accounts for more of the Russian economy than any individual region in the U.S.

Geopolitical Futures subscribers likely have noticed that our daily Watch List recently has sharply focused on regional economic problems in Russia. The above map helps explain why. Russia’s economy has been severely hurt by the drop in oil prices, and as a result, the Russian government is instituting spending cuts on social services across the federation. The first place those cuts will manifest will not be Moscow, but rather poorer and more isolated districts such as the Far East or Siberia. Small protests in an oil-producing region in the Ural Federal District last week attracted our attention precisely because we expect Russia’s economic issues to manifest in these areas first. The regime that rules from Moscow possesses a great deal of wealth in absolute terms, but it is not enough to govern the rest of Russia without a firm grip that will have to tighten as Russia burns through reserves and cuts more social spending.

The U.S. is roughly half the size of Russia in area, but still is a very large country relative to most. The U.S. is also a federation of 50 states with different economic interests. The union of these states was not always a foregone conclusion: The U.S. first briefly existed as a confederation, and a Civil War was fought before the union of states was truly solidified. Even so, the states that make up the union have always been more interconnected than Russia’s disparate regions. Russia’s population clusters along its western border with Europe and its southern border with the Caucasus, and all of Russia’s rivers and infrastructure point west, which is why so much of its economy is concentrated in one area. The U.S. population is increasingly concentrated on coasts and in urban centers, but the country’s internal circulatory system since 1803 has been the Mississippi River; its vast and navigable water system explains why the economies of various states have developed as they have.

Like Russia, the U.S. Department of Commerce also divides the U.S. into nine discrete regions for bureaucratic purposes. What stands out in the map above is that while the U.S. certainly has regions that account for a greater share of the U.S. economy, overall, economic activity is much more spread out. The Southeast region, even without Texas, actually contributes the most to total GDP. The Mideast and the Far West are not far behind. New York City is the U.S.’ largest, and its greater metropolitan area comprises about 7 percent of the country’s total GDP. But that pales in comparison to the outsized role Moscow plays in the Russian economy.

Furthermore, almost every U.S. region has a major state economy. In Russia, the Central Federal District and a few far-flung oil-producing regions produce the country’s wealth. In the U.S., wealth is far more spread out. California, Texas and New York are the three biggest state economies, located about as far away from each other as they can be on a map. They are engines for regional economies as much as they are important contributors to the national economy. The situation is by no means perfect. The Rocky Mountains region is by far the least important in terms of the economy, representing just 3.4 percent of the country’s total GDP. But compared to Russia, the U.S. economy is less dependent on government handouts from Washington than Russia’s various regions are dependent on money from Moscow.

All national economies are regionalized at some level. But the point here is to show how broad patterns of regionalization can reveal much about the economic structure and relative power of particular countries. In Russia’s case, looking through this lens allows us to see how concentrated wealth is in the Russian Federation, which puts a great deal of strain on one district, and the capital city in particular. As a result, Russia must find the right balance of carrot and stick to rule a vast territory at a time when its chief moneymaker – oil exports – is less profitable than Moscow expected. Russia’s greatest problems are internal and will require more of the stick, because the carrots have run out. U.S. wealth, on the other hand, is spread out much more evenly between its various regions. That means the U.S. economy is far more dependent on regional economic centers than on decisions made in Washington, and this is a source of power for the country.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President