By George Friedman

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson will be attending a meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Donald Trump on April 6-7. Reuters reported on March 21 that Tillerson, therefore, will skip an April 5-6 meeting of NATO foreign ministers, the first time a U.S. secretary of state will miss such a meeting since 2002. The State Department followed up by saying that the U.S. has decided to propose new dates for the NATO summit. Nevertheless, the key point is that Tillerson views the Trump-Xi meeting as more important than the NATO ministers summit.

The meeting between Trump and Xi is critical and comes amid serious tension between the two countries. This tension is compounded by Trump’s position on China-U.S. trade, security concerns in the South and East China seas, and Trump’s decision to speak directly with the president of Taiwan, challenging the “One China” policy, even though he later agreed to honor the policy.

Most meetings of international leaders are neither dramatic nor important. Leaders are obligated to attend, but usually, nothing comes of them. But this summit between Trump and Xi is of prime importance. It brings together the leaders of the world’s first and second largest economies, whose militaries are brushing up against each other in the air and at sea. To the extent that summits matter, this one does. And if nothing comes of it, that would be an ominous sign. Obviously, the U.S. secretary of state has to be at that meeting.

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, left, talks with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, right, as he arrives for a bilateral meeting at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse on March 18, 2017 in Beijing, China. Mark Schiefelbein – Pool/Getty Images

That it coincides with the NATO meeting was not intended as a slap at NATO. The NATO meeting likely didn’t even come up, and if it did, as Reuters has reported, it wasn’t the primary concern when planning U.S. officials’ schedules and priorities. Figuring out when and where Trump and Xi would meet likely involved difficult negotiations. These meetings usually do, especially when they are tense and stakes are high. The fact that Xi will go to the U.S. – and especially that he reportedly will go to Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida – is one of those minor symbolic victories for Trump. It also indicates that, having agreed to this visit, Xi will be much tougher on substance. To put it in American terms, this is a major league meeting.

The NATO meeting, by comparison, is minor league. NATO constantly has meetings. There are few substantive outcomes. NATO meetings used to be of vital importance during the Cold War. Now those discussions rarely intersect the main issue. The United States, wisely or not, has been fighting a war for 16 years in the Middle East, and that war is now entering another phase in Syria with U.S. forces being deployed there. As an institution, NATO has been of little material support to the United States. Many nations provided some support in Afghanistan, but much of this was symbolic. It was insufficient to have any material effect on the war’s outcome. Some smaller countries sent small forces because that was all that they could send. Other, larger countries sent far fewer forces than they could have because they didn’t want to send more. The British and Canadians put far more skin into the game, but that was because of their close ties to the U.S., not because of NATO.

It is understandable that some NATO members would choose to abstain from this 16-year war in the Middle East, as NATO’s charter does not require “out of area” deployments. But NATO is a military alliance, and the organization has been of little value to the U.S. Under these circumstances, NATO members should not be surprised that the U.S. secretary of state finds a meeting with the Chinese president more significant than a meeting with NATO foreign ministers.

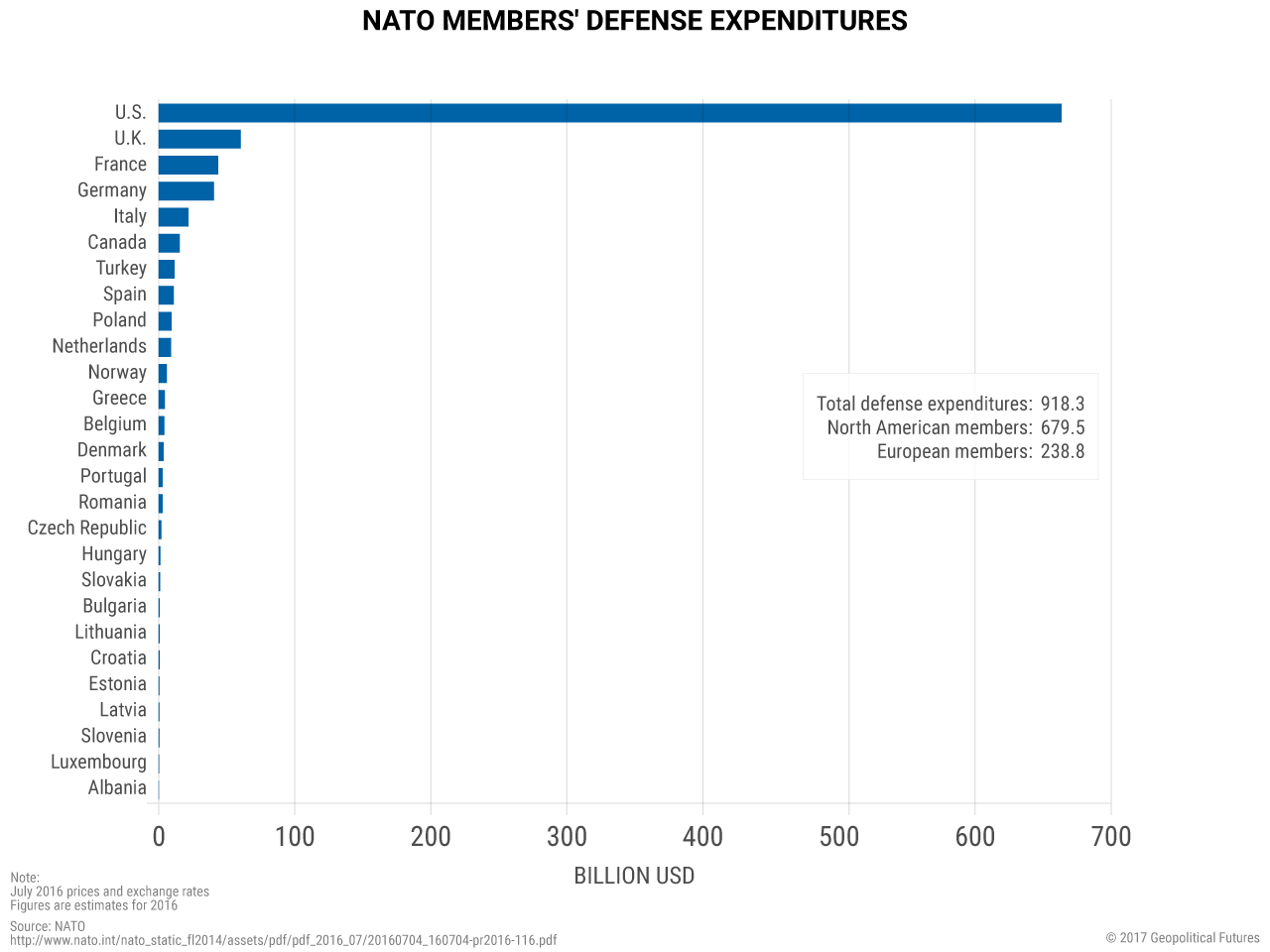

This goes to the deeper issue concerning the alliance. It is not clear that Europe has a serious commitment to NATO. Undoubtedly, ringing declarations will come out of this and other such meetings but not the money to fund the sentiments. NATO members have made a commitment to raise their military budgets to 2 percent of GDP, which would be a little more than half the percent of GDP the U.S. spends on defense. Secretary of Defense James Mattis pointed this out to NATO defense ministers, and he was supported by NATO’s secretary general. A very strong case can be made that there is no reason for any further meetings without dramatic increases in NATO members’ military budgets. The Europeans have made a commitment. They will either meet it or not. That will determine the need for meetings. But at NATO, endless meetings have become a substitute for decisive action.

Some will point out that members’ direct contributions to NATO are not out of line with U.S. contributions. That may be true, but wars are not fought with NATO contributions. Should war come, it will have to be fought with the full military capability of all NATO members. But at this point, American divisions, aircraft and navies will provide the decisive force to NATO if war breaks out. Should the Russians move westward into the Baltics, for example, only American forces would have sufficient size and depth to fight them off. This is why the U.S. war in the Middle East should be considered a NATO affair. Without NATO relief, U.S. forces will be strained to supply the force needed in Europe, which is why the Trump administration is speaking about a substantial increase in the U.S. defense budget, so that forces in reserve for a conventional war can be upgraded.

It is in this context that NATO foreign ministers are dismayed at Tillerson’s decision to attend the showdown between the U.S. and China. The China meeting matters greatly. The NATO meeting does not because the Europeans have not taken NATO seriously for a long time. They have not treated it like a critical military alliance, but as something bonding the U.S. and Europe together. Increases in defense spending would be far more effective.

Geopolitically, the rotation of interest away from NATO makes perfect sense. Russia is a pale shadow of the Soviet Union, reduced to hacking emails or spreading misleading tweets. There is little to fear in terms of war. Perhaps NATO should be abolished. But for some reason, the Europeans want neither to abolish nor to keep their commitments to the alliance. It is good that Tillerson will not be at this meeting. The American presence would likely make conversation uncomfortable. The Europeans will be there by themselves (with the Canadians, of course). Maybe in private they can figure out what they think they are doing.