By Jacob L. Shapiro

By all accounts, Spain should be a European success story. As recently as 2012, the country was teetering on the edge of economic meltdown. Its economy contracted by 3 percent that year. Unemployment climbed to over 20 percent, on its way to a staggering 27 percent by the following year. A banking sector collapse was averted only by a 51 billion-euro ($60 billion) bailout package from the European Stability Mechanism that June. There was real fear in Europe that Spain might be the next Greece.

That fear turned out to be misplaced. Over the past three years, gross domestic product growth has averaged over 3 percent. Unemployment has dropped to 17 percent and is projected to fall below 14 percent next year. The European Commission reported that wage growth in Spain is expected to rise faster than inflation in 2019 – so not only are more people finding jobs, but they are getting paid more as well. The government succeeded in pulling Spain back from the brink, and according to the Bank of Spain, it cost the country itself only 26.3 billion euros – not a bad deal considering that its economy is the fourth-largest in Europe and only slightly smaller than Russia’s.

Yet, despite Spain’s much improved economic position, Spanish politics are more unstable now than they have been in decades. With a government plagued by a corruption scandal for years, Mariano Rajoy, who had served as prime minister since 2011, was ousted in a no-confidence vote last week – the first Spanish head of state to have lost such a vote since the 1978 constitution was adopted. Rajoy will be replaced by Pedro Sanchez, head of the Socialist Party, which holds only 84 of 350 seats in parliament and has already promised to call early elections. Spain now joins Italy, France, Germany and the United Kingdom as the latest European country with an extremely weak government.

This isn’t the way things are supposed to work. Economic recoveries don’t usually result in political upheavals. But that is indeed what has happened in Spain. In addition to the prime minister’s ousting, the issue of Catalan independence remains unresolved. The day after Rajoy’s deposal, Quim Torra was sworn in as Catalan president – the first since Rajoy dissolved the Catalan regional government last October and instituted direct rule after an independence referendum that Madrid declared illegal but proceeded anyway. Rajoy’s heavy-handed approach to Catalonia apparently hasn’t dented its desire for sovereignty. During his swearing-in ceremony, Torra committed to creating an independent Catalan republic.

A similar scenario has played out across Europe. All headline economic statistics throughout the EU are trending upward, exceeding even the most optimistic projections of a few years ago. But the moderate economic recovery has been accompanied by increasingly unstable politics. In Germany, the anti-establishment party Alternative for Germany is now the third-largest political party. In Italy, a hodgepodge of euroskeptic, anti-establishment parties have formed a coalition to lead the new government. And in France, if the National Front had a leader with a surname other than Le Pen, it may well have prevailed in last year’s elections.

Spain is part of this European trend – and it’s not just because of Rajoy’s fall from grace or Catalonia’s irascibility. It is part of a larger degradation of what has been until now Spain’s predominantly two-party political system. A recent poll by Spanish newspaper El Pais showed that if elections were held today, the top two vote-getters would be anti-establishment parties: Ciudadanos (29.1 percent) and an electoral alliance led by Podemos (19.8 percent). Rajoy’s Popular Party and Sanchez’s Socialist Party – the only two parties in Spain that have formed governments since 1982 – would come in third and fourth place, respectively.

Podemos supports left-wing economic policies, including increased state control over the economy and government services, but it’s also a nationalist party. Ciudadanos, the current frontrunner by a wide margin, may be anti-establishment but it’s not anti-EU. It has combined Spanish nationalism with pro-EU and classical liberal policies like lower taxes and free trade. It’s comparable to French President Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche party, and indeed, the two parties have even reportedly been in touch recently, offering hope to Europhiles that out of this weekend’s chaos might come a Spanish government supportive of French and German proposals to reform the EU by giving Brussels expanded powers.

But for Spain, unlike Germany and France, this is all complicated by the fact that what is at stake is not just the status of the European Union but the future of a unified Spain itself. Ironically, Ciudadanos began as a Catalan political party – its headquarters are still in Barcelona. And yet, Ciudadanos has taken a harsh line on the issue of Catalan separatism, pushing instead for a more tightly knit Spanish nation-state. Podemos, headquartered in Madrid, has thus far presented itself as more accommodating than either the outgoing Spanish government or Ciudadanos when it comes to Catalonia’s independence movement. That makes some sense. It would appear hypocritical for Podemos to support anti-EU sentiment in Spain and then reject nationalist sentiments in Catalonia.

Of course, all countries have these sorts of divisions. In France, the divide is between Paris and the rest of the country. In Germany, the old East-West split of the Cold War is still alive and well. In the U.K., Brexit has reanimated conversations on just how much authority Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland really have.

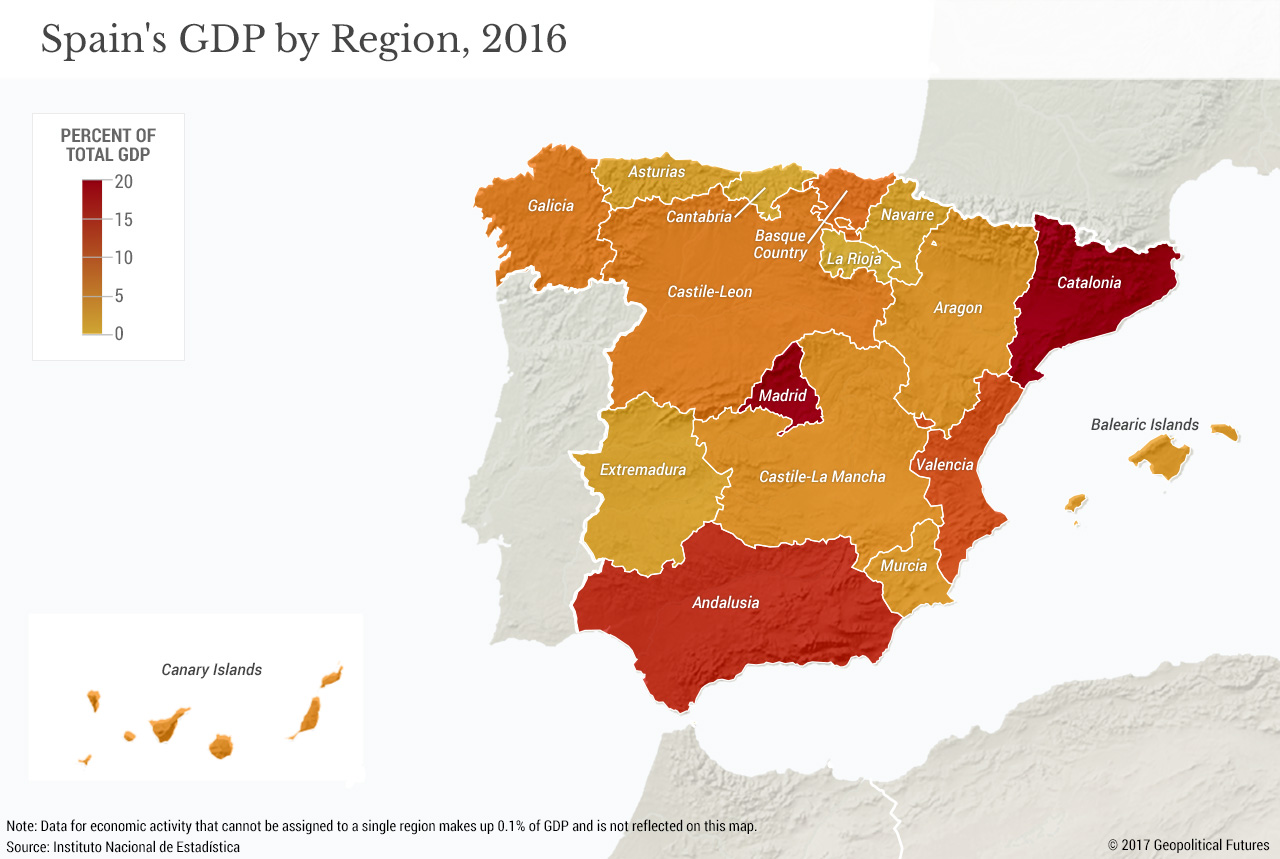

In Spain, the primary (but by no means only) division is between the country’s leading GDP contributor, Catalonia, and its second-largest contributor, Madrid. This is a riddle no Spanish political entity has ever really solved. Even at the height of the Spanish Empire’s power in the 1640s – when Spanish armies outnumbered the combined military manpower of France, England and Sweden – Spain was in danger of tearing itself apart. Catalonia, along with Aragon and Valencia, had its own independent legal and tax systems at the time, and it even revolted against the crown when Madrid tried to integrate Catalonia’s economy into the empire.

During those days, it was the Castile region, with its capital moved to Madrid by Phillip II in 1561, that held the fractious kingdom together, both with its soldiers and with its money. And though Spain has had its fair share of instability since the empire fell, Castile has always been the force that kept Spain together, whether by war, dictatorship or, most recently, constitutional arrangement. Catalonia has at times opposed this, but never wholly and never successfully. Even so, the 2008 financial crisis stirred up old animosities because a passionate faction of the Catalan population no longer wanted to send its tax revenue to Madrid – a desire that has not abated even as the Spanish economy has recovered.

Other European countries have been keeping a close eye on developments in Catalonia. In some parts of Europe, particularly in the east and the Balkans, the sacrosanctity of borders is sometimes viewed not as a valuable principle in and of itself but as a paltry ideological justification for empowering some at the expense of others. Catalonia may be an internal problem for Spain, but self-determination is an issue that has long plagued the whole continent, even if it has been relatively dormant in recent decades. Disenchantment with establishment politics and the debate over the optimal degree of sovereignty to be ceded to the European Union is not just a Spanish concern but a European problem.

And while all this is happening, keep in mind that, for Spain, this is now what it looks like when things are generally going well. Imagine what it would look like if they weren’t, and you’ll understand how frayed the fabric of Europe has become.