By Kamran Bokhari

Five weeks have passed since the Iraqi government formally launched efforts to retake Mosul from the Islamic State. Baghdad has made progress with Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) entering the city’s easternmost districts. But the ISF has a long way to go before pushing IS out of the country’s second largest city. The ISF could take months to regain control of a city they abandoned in only a few days in June 2014.

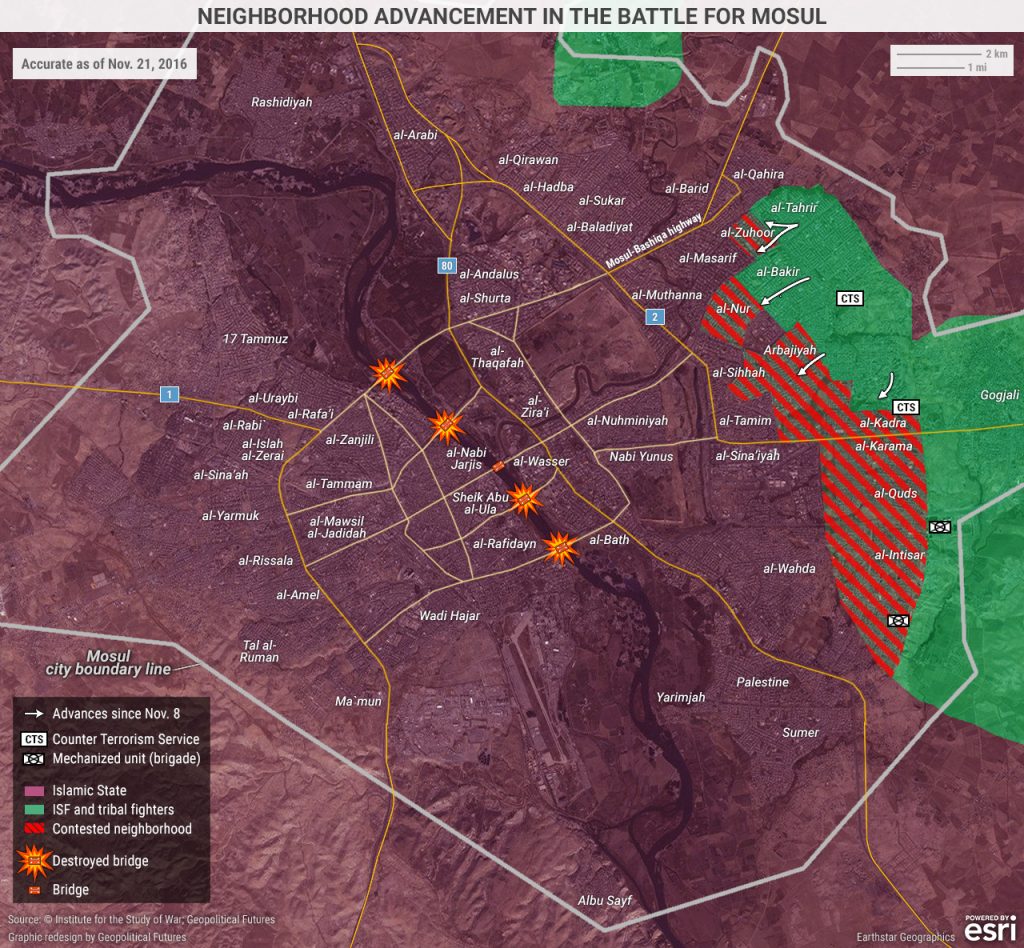

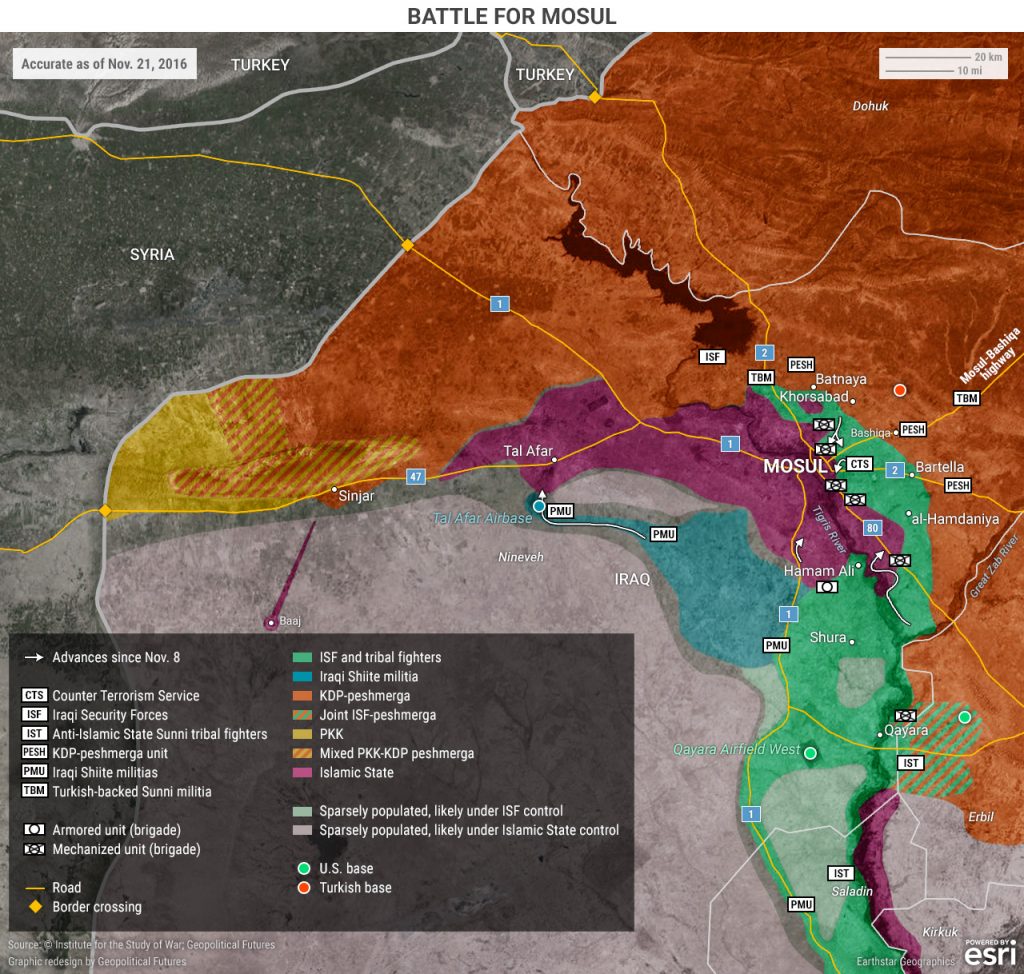

U.S. airstrikes on Nov. 22 destroyed a fourth bridge on the Tigris River in Mosul. The city has only one remaining crossing that connects its eastern and western parts, which are nearly split in half by the Tigris. On the ground, Iraq’s U.S.-trained Counter Terrorism Service forces are the frontline soldiers engaging fighters of the jihadist regime in districts on the city’s eastern periphery. Meanwhile, most of the task force’s 100,000 fighters (composed of Iraqi army and police units, peshmerga fighters from the autonomous northern Kurdistan region, Shiite militiamen and Sunni tribal fighters) are trying to lock down areas to the north, south and the west of Mosul.

Considering that the Iraqis are pushing into the city from the east, IS fighters are expected to retreat to the west, in the direction of their core turf in eastern Syria. This was the direction from which IS fighters mounted the assault on Mosul when they seized the city two and a half years ago. It remains the main supply route to ferry fighters and matériel. For this reason, the Iraqis have sought to close off the western corridor into and out of the city.

Units of the Popular Mobilization Force (PMF), a Shiite-dominated militia, were assigned this task for two reasons. First, there aren’t enough regular Iraqi forces to mount a push into the city as well as lay siege to it. Second, deploying the PMF to the ground battle could undermine the effort, given the logic of the Shiite-Sunni conflict, which IS hopes to exploit as it seeks to counter the assault on Mosul.

The PMF is being used to prevent IS from receiving supplies and to cut off an escape route for retreating IS fighters. Ensuring the latter is important so that the IS force currently in the city does not escape to fight another day. A Nov. 23 report by a Kurdish news agency states that the IS high command has asked its fighters to withdraw from Mosul. This is likely part of psychological operations by the anti-IS coalition.

Because the Iraqis have made little progress since entering the outlying districts in the east, IS has no reason to retreat anytime soon. In our detailed assessment of what to expect from the Mosul offensive, published 10 days after the offensive began, we noted that IS strategy is to hunker down and fight so the coalition will pay a heavy price for each square mile of territory it retakes. While taking Mosul was a massive victory for IS that forced the ISF to abandon the city, the IS knew that U.S.-supported Iraqis would return to retake the city. The jihadist regime has had nearly two and a half years to prepare for this battle.

While IS hopes to sustain a war of attrition as long as possible, it is aware of limits on how long it can hold out. Therefore, a secondary part of its strategy in Mosul involves withdrawing remaining forces to rural areas to sustain a guerrilla offensive against the ISF-led force. IS’ goal at that time will be to prevent the Iraqis from consolidating control over the city. In order to do this, IS must have sustained freedom of movement in rural areas.

A soldier from Iraqi Special Forces 2nd Division takes up a position to prepare for a suicide bomb vehicle reportedly moving towards their position as they engage with Islamic State fighters in Mosul’s Karkukli neighborhood, on No. 14, 2016. ODD ANDERSEN/AFP/Getty Images

The Iraqis recall how IS’ predecessor organization revived itself after being weakened in 2008, when U.S. military forces succeeded in turning Sunni tribal forces against the jihadist movement. The challenge for the Iraqis is that even with PMF assistance they cannot ensure IS would not disappear into the countryside. Taking the town of Tal Afar, west of Mosul, is key to Iraqi efforts. The PMF is entrusted with this goal because before IS took over Tal Afar, the town had a Shiite majority. It is hoped that sectarian fallout will be minimal.

Because the city has a sizeable ethnic Turkoman population – a significant number of whom are Sunni – Turkey has been threatening to intervene militarily against any efforts to expand Shiite control over not just Tal Afar, but also Mosul and the wider Nineveh province. In many ways, the only way to dislodge IS from Mosul and surrounding areas involves using a Shiite-dominated military force. IS was able to control large parts of Iraq’s Sunni areas because it is the only force among the country’s sectarian minority.

IS’ weakening would lead to Shiite domination over traditionally Sunni areas. Iraqi Sunnis have been divided and weak since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. However, an insurgency by Sunni nationalists and jihadist factions prevented Shiites from controlling these areas. This effort culminated in IS dominating large parts of Sunni Iraq.

Given that strong mainstream Sunni forces do not exist, these areas can only regained from IS with a majority Shiite Arab force, along with the Kurds. Kurdish ambitions to control areas taken from IS cause another problem. It not only upsets efforts to mobilize Sunnis against IS, but also affects cooperation between forces loyal to the central Iraqi government and those loyal to the Kurdish regional authority. This ethnic and sectarian quandary makes retaking Mosul all the more challenging.

Iraqis now must deal with the nightmare of urban combat and an enemy entrenched in the city. Troops in the city will advance at a crawl given the resistance from IS snipers, mortar fire and suicide bombers in close quarters. In addition, troops must hold territory they have cleared. That involves dealing with locals, both in terms of providing basic assistance to civilians and finding trustworthy allies.

The sectarian dynamic complicates each of these efforts, which likely will further slow the advance into the city. The coalition is working hard to involve as many Sunnis in the front lines as possible. But the liberating force as a whole is made up of the sectarian “other.” The ISF on many occasions will find itself bogged down in attempts to retake the city, and reinforcements – especially in the form of militias – will further polarize the situation.

Starting on Oct. 17 from the town of Gwer, to the southeast of Mosul, Iraqi forces covered a distance of 25 miles in the first two weeks. For the past three weeks, however, the offensive has become extremely slow, with Iraqi forces tied down in the city’s outlying districts, advancing only a handful of square miles. IS forces will feel the pressure from the bridges’ destruction and Shiite militias trying to seal up territory on the city’s western flank. But the Iraqis still must push through a lot of urban terrain where IS has the upper hand.

The liberating forces not only must advance militarily, they also must manage the liberated areas. The extent to which they succeed at the latter shapes the former. By no means is the advance of Iraqi forces a linear process. Thus, what we are facing is a protracted battle that may last through winter and into spring.