By George Friedman

Last week, Iran confirmed that it test-fired a ballistic missile. The United States has responded by imposing new sanctions on Iran and stating that Iran remains both a major source of terrorism and a threat to American national interests. A review is now underway concerning U.S. policy toward Iran. At the same time, President Donald Trump has declared his intention of crushing the Islamic State, which has been U.S. policy since the emergence of IS.

U.S. National Security Adviser Michael Flynn speaks during the daily press briefing as Press Secretary Sean Spicer (L) looks on at the White House in Washington, on Feb. 1, 2017. Flynn signaled a more hardline American stance on Iran, condemning a recent missile test and declaring he was “officially putting Iran on notice.” NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images

U.S. strategy in Iraq prior to the 2007 surge was to oppose both Shiite and Sunni claims to power in Iraq. The United States tried to craft a government in Baghdad that was independent of both major factions, ideally secular and closely aligned with the United States. That government was created, but it was never effective. The Shiites, supported by the Iranians, deeply penetrated the government, and more importantly, the government never had broad support beyond the coalition that backed it. The most dynamic forces in Iraq were deeply embedded in the Shiite and Sunni communities. Both drew strength from outside Iraq – the Sunnis from Saudi Arabia and the Shiites from Iran.

What the United States wanted to create was very different from the reality on the ground. In the surge, the U.S. recognized this, saw the Iranian-supported Shiites as the greater threat and tried to counterbalance them by reaching a financial and political understanding with the Sunni leadership. Apart from providing the U.S. with an opportunity for a graceful exit, the surge didn’t solve the strategic problem the U.S. was dealing with. IS arose as the champion of a substantial part of the Sunni Arab population, and the Iraqi government became, to an imperfect but real extent, captive to Iran. The U.S. remained powerless to craft the Iraq it wanted.

The United States now has three broad strategic options. The first is, after 15 years of ineffective fighting, to accept defeat in the region, withdraw and allow the region to evolve as it will. The advantage of this strategy is that it accepts the reality and consequences of the previous 15 years, and it halts an ineffective approach. The weakness of this strategy is that in accepting the evolution of the region, the U.S. could face an increasingly powerful Sunni world and a powerful Shiite Iran. After the sense of relief may come an unbearable headache.

The second option is to use American force to crush IS and isolate Iran, or failing that, engage Iran in some form of military action, possibly directed at its nuclear program. The United States does not have a military force large enough to simultaneous wage war from the Mediterranean to Iran, and also in Afghanistan. Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said at the beginning of the Iraq war that you fight with the army you have. He should have added that if the army you have is insufficient, you will lose, or at most, face an endless stalemate. The goal of this strategy would be to crush not merely the current organizations fighting for Sunni and Shiite causes but to destroy the will of the Arab and Persian worlds to create new organizations out of the ashes of the old. The United States has never fought a major foreign war without a coalition of forces. Its distance from the Eurasian battlefield means that support from other forces for the logistical effort is essential. This is why there is discussion of an alliance with Russia. But Russia does not have the same interests in Iran as the United States, nor is it looking for the same outcome.

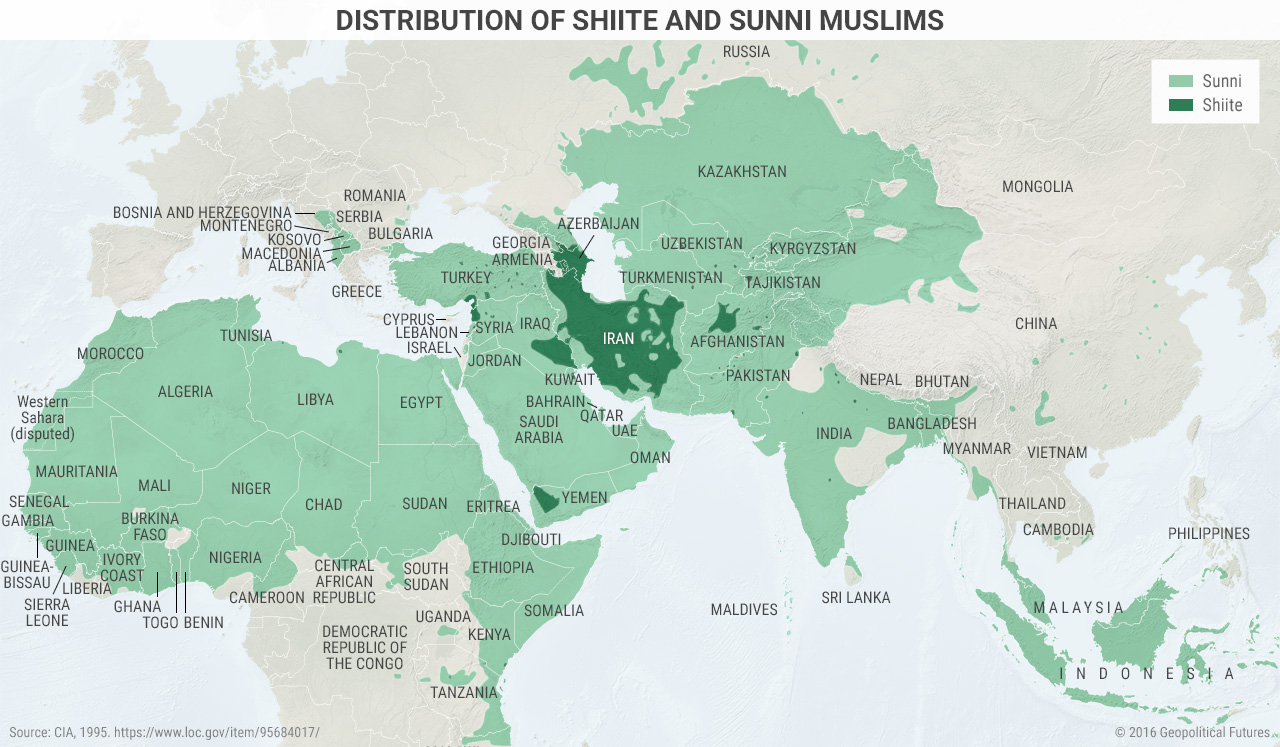

The third strategic option is built on two realities. First, the U.S. has limited forces, reluctant or discordant allies, and cannot win a war on this scale. Second, the Islamic world is deeply divided along religious and ethnic lines. There is the religious split between Shiites and Sunnis. There is the split between the Arab and non-Arab world. In other words, Islam is not of a single fabric and these divisions are its point of vulnerability. The third strategy would require allying with one faction to give it the thing it desires the most – the defeat of the other.

From the beginning of American history, the U.S. has used the divisions in the world to achieve its ends. The American Revolution prevailed by using the ongoing tension between Britain and France to convince the French to intervene. In World War II, facing Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union, the United States won the war by supplying the Soviets with the wherewithal to bleed the German army dry, opening the door to American invasion and, with Britain, the occupation of Europe.

Unless you have decisive and overwhelming power, your only options are to decline combat, vastly increase your military force at staggering cost and time, or use divergent interests to recruit a coalition that shares your strategic goal. Morally, the third option is always a painful strategy. The United States asking monarchists for help in isolating the British at Yorktown was in a way a deal with the devil. The United States allying with a murderous and oppressive Soviet Union to defeat another murderous and oppressive regime was also a deal with the devil. George Washington and Franklin D. Roosevelt both gladly made these deals, each knowing a truth about strategy: What comes after the war comes after the war. For now, the goal is to reach the end of the war victorious.

In the case of the Middle East, I would argue that the United States lacks the forces or even a conceivable strategy to crush either the Sunni rising or Iran. Iran is a country of about 80 million defended to the west by rugged mountains and to the east by harsh deserts. This is the point where someone inevitably will say that the U.S. should use air power. This is the point where I will say that whenever Americans want to win a war without paying the price, they fantasize about air power because it is low-cost and irresistible. Air power is an adjunct to war on the ground. It has never proven to be an effective alternative.

The idea that the United States will simultaneously wage wars in Syria, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan and emerge victorious is fantasy. What is not fantasy is the fact that the Islamic world, both strategically and tactically, is profoundly divided. The United States must decide who is the enemy. “Everybody” is an emotionally satisfying answer to some, but it will lead to defeat. The United States cannot fight everyone from the Mediterranean to the Hindu Kush. It can indefinitely carry out raids and other operations, but it can’t win.

To craft an effective strategy, the United States must go back to the strategic foundations of the republic: a willingness to ally with one enemy to defeat another. The goal should be to ally with the weaker enemy, or the enemy with other interests, so that one war does not immediately lead to another. At this moment, the Sunnis are weaker than the Iranians. But there are far more Sunnis, they cover a vast swath of ground and they are far more energized than Iran. Currently, Iran is more powerful, but I would argue the Sunnis are more dangerous. Therefore, I am suggesting an alignment with the Iranians, not because they are any more likable (and neither were Stalin or Louis XVI), but because they are the convenient option.

The Iranians hate and fear the Sunnis. Any opportunity to crush the Sunnis will appeal. The Iranians are also as cynical as George Washington was. But in point of fact, an alliance with the Sunnis against the Shiites could also work. The Sunnis despise the Iranians, and given the hope of crushing them, the Sunnis could be induced to abandon terrorism. There are arguments to be made on either side, as there is in Afghanistan.

In my opinion, what cannot be supported is simultaneous conflicts with Sunnis and Shiites, Arabs and Persians. What we learned in Iraq is that we will not win such a conflict. Attempting what failed in Iraq on a far larger scale makes little sense. Dividing your enemies is a fundamental principle of strategy. Uniting them makes little sense. Therefore, simultaneously waging war on Sunnis and Shiites is irrational. Simply withdrawing from the region carries enormous long-term risks.

In the end, Washington wanted to defeat the British and Roosevelt wanted to defeat Hitler. Without the French or Soviets, these wars would have been lost. In the end, the Bourbons and communists were destroyed. Washington and Roosevelt were in no rush. There is always time for the winner to pursue the end he wants. There is never time for the loser.