By Jacob L. Shapiro

The small Syrian city of Palmyra, well-known for its ancient ruins, has changed hands for a third time in the last year and a half. Islamic State forces launched a coordinated offensive in the area on Dec. 8, and by Dec. 11 the city had fallen. IS forces are now threatening Syria’s Tiyas air base, approximately 30 miles west of Palmyra, and fighting continues as of this writing, though Syrian forces seem to be holding their ground for now.

The last time Palmyra changed hands was March, when a hodgepodge of 5,000 Syrian army forces and various militias backed by Russian air support took control from IS. That “victory” was largely a hollow one, more a result of a well-managed IS retreat than the overwhelming victory depicted by Syria, Russia and the media. On March 28, we wrote: “IS’ capitulation in Palmyra is not going to be permanent. … IS seized Palmyra because it had the opportunity to do so, and it will wait for further opportunities to arise in the future.”

That future is now, and it has serious implications for the major players involved: IS, Russia and Syria. For IS, Palmyra was a target of opportunity. The fighters aligned with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad who took Palmyra last March were not a uniform force, and their strength has diminished in recent months. Some Iranian militias involved in the March offensive against IS were pulled back to Iraq to support the ongoing Iraqi assault against Mosul. Syrian forces were taken from the front lines in Palmyra to support the Assad regime’s fight to secure Aleppo from Syrian rebels. Palmyra became a soft target for a quickly massed and well-executed IS attack. Despite the political and popular prognostications regarding IS’ imminent collapse, IS’ operations in the Palmyra area show that it remains a capable fighting force.

A photographer on March 31, 2016 holds a two-year-old photo of the Temple of Bel in front of the historic remains after the temple was destroyed by Islamic State jihadis in September 2015, in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra. JOSEPH EID/AFP/Getty Images

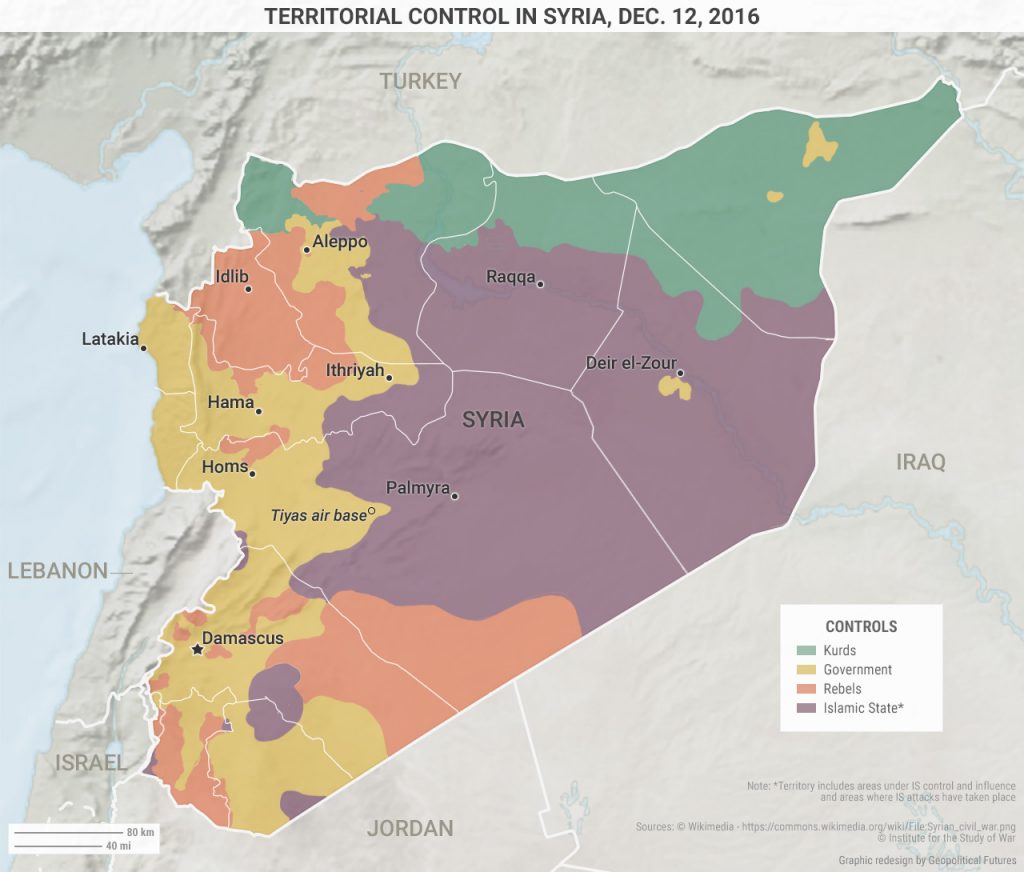

IS never capitulated on Palmyra even after retreating from the city last March. In May, for example, IS launched an operation to secure the al-Sha’er natural gas field north of Palmyra, shelling Tiyas air base in the process. That significantly damaged the base as well as Russian attack helicopters stationed there. IS is focused on Palmyra because it has a major strategic interest in holding this area. The key strategic point is not specifically Palmyra, but rather the M-20 Highway, a straight shot from Palmyra to the well-defended Deir el-Zour, IS’ second most important city. IS doesn’t necessarily need to hold Palmyra, and the city is not an easily defensible position, as changing hands three times in 18 months indicates. But Palmyra is where three highways meet to connect Homs, Damascus and Deir el-Zour. When IS retreated from Palmyra in the past, it maintained control over most of the section of the M-20 that leads to Deir el-Zour. From IS’ perspective, the more of this stretch of highway it can control, the more secure its position.

Besides this basic strategic value, IS chose this move now for two other reasons. The first is that IS has lost many of its previous sources of arms and matériel. Turkey has clamped down on the border in northern Syria and is supporting Syrian rebel assaults on the IS-held city of al-Bab. In Iraq, IS territories are under significant strain. Videos released by al-Amaq, IS’ media arm, show IS fighters in Palmyra seizing large quantities of arms, ammunition and tanks left by the retreating forces. In this sense its attack on Palmyra reveals one of IS’ biggest weaknesses: the inability to produce its own armor or weapons. The second reason is that the Assad regime seems to have finally gained control of Aleppo, with state-run TV reporting that the city officially was “liberated” by Assad’s forces on Dec. 12. The Syrian army is a far cry from what it used to be, and significant rebel pockets still exist, especially in Idlib province. But the prospect of Assad consolidating his gains and eventually setting his sights on attacking IS means IS needs to divert Assad’s resources away from consolidation efforts to strengthen its own position relative to Syrian forces, should they begin to focus more on IS positions.

IS’ position compared to that of Assad’s forces is actually better than it may seem. While Syrian rebels in Aleppo appear to be nearing defeat, the remaining areas under Syrian rebel control are directly between Assad’s main stronghold on the coast and resupply routes to Aleppo. As the above map shows, the supply line from Assad’s main forces to Aleppo is actually a narrow band extending through Hama to Ithriya, and up to Aleppo. These roads are vulnerable to potential IS attack, and IS has continued to attack villages and areas in and around Homs in recent months. IS needs the Syrian rebels to continue to be a thorn in Assad’s side to prevent Assad from coming after IS in full–strength. IS can help the rebels do that by threatening Syrian supply lines and forcing Assad to move his forces away from the main theater with the rebels. It is unlikely that IS is contemplating an assault on Homs, which currently isn’t in IS’ strategic interests. But if the defenses at Homs resemble those at Palmyra, IS won’t hesitate to take advantage.

For both Russia and Syria, losing Palmyra, even if only temporarily, is deeply embarrassing. Details on the number of forces involved in this recent battle are still sketchy, but Russian and Syrian reports claim that a large IS force between 4,000 and 5,000 fighters and backed by tanks and armored vehicles approached the area from multiple directions. These IS forces, according to reports, were able to drive back the city’s defenses despite Russian airstrikes that purportedly killed more than 300 IS fighters. This is not an inconceivable number. IS has maintained a presence in this region even after retreating from Palmyra in March. It may have augmented those forces with fighters pulled out of Mosul before the Iraqi assault on the city began in October, and possibly with elements of the Caliphate Army, a brigade-size force of IS’ most elite fighters that Raqqa deploys wherever it is most needed.

That said, Syria and Russia also have every reason to exaggerate the size of the IS force to hide their own deficiencies. It is also entirely feasible that IS’ size was much smaller, and they simply executed a well-crafted plan of attack. According to the Institute for the Study of War, after Russia and Iran pulled back their garrisons, only a few hundred poorly-trained militiamen from Syria’s National Defense Forces remained to defend Palmyra. It would not take an IS force of overwhelming size to make quick work of untrained and unmotivated Syrian forces.

For Russia, IS’ retaking of Palmyra is a blow to its image. In war, image is usually less important than reality, but this isn’t really Russia’s war. One of Russia’s primary reasons for being in Syria is to gain prestige and to hide its own weaknesses with a limited show of force in Syria. Russia announced its intervention in Syria a few months after Palmyra originally was taken by IS. When Syrian and Iranian forces retook the city with Russian support, the Russians went out of their way to publicize their role in the success. They even deployed an orchestra to the city to play a classical music concert in the ancient ruins, featuring a selection from Bach’s “Partita No. 2” and Prokofiev’s “Symphony No. 1” in its entirety. A demonstration of Russian weakness is not what Russian President Vladimir Putin has in mind for his country’s involvement in Syria.

Adding insult to injury, Russia all but declared mission accomplished last March when it announced it was withdrawing many of its forces from Syria. In reality, Russia has not been able to pull back. Even with continued Russian air support, Assad’s forces have taken well over a year to consolidate control over Aleppo, and that fight still is not over, despite the boasts of Syrian state-run TV. Now in Palmyra, much-touted Russian gains have been overturned, despite continued Russian airstrikes in the area. It shows how limited airpower can be in a conflict like this, and how limited Russia’s intervention in the Syrian conflict actually has been. Russian airstrikes were unable to protect Palmyra from IS fighters, who have no air assets to speak of, and IS fighters are now attacking an air base that normally houses two fixed-wing attack squadrons of Syrian air force Su-24 and Su-22 fighter jets. With each passing month, Russia risks being bogged down in an interminable conflict in the middle of the Syrian desert.

For the Assad regime, the news of Palmyra tarnishes recent gains the regime has made in Aleppo, and shows the difficult position in which the Assad regime remains. Assad’s forces have fought a brutal war for almost five years, and those left are tired and bogged down in securing Aleppo, while many other rebel strongholds still need clearing. That Assad has had some recent success in Aleppo should not obscure that his forces, even with air support, are vulnerable to attacks like the fairly limited offensive in which IS is currently engaged. Assad simply does not currently have enough forces at his disposal to defeat all of his enemies.

IS retaking Palmyra does not change the balance of power on the ground – it merely illuminates it. The Islamic State, despite myriad challenges, remains a highly capable and opportunistic military fighting force fortifying its most important strategic holdings in Raqqa and Deir el-Zour, in preparation of future battles. Russia’s intervention in Syria has been, and remains, limited in scope and effectiveness. The Assad regime is propping itself on air power and limited Russian support, but it lacks the force necessary to pacify the country, its recent successes in Aleppo notwithstanding. The war goes on.