By Jacob L. Shapiro

There’s a tendency to view every major political scandal in China as a litmus test for the president. So tightly is power held in his hands that whatever happens under his watch is either an indictment of his power, and thus the viability of the Communist Party of China, or a validation of it. It’s a tempting reaction, but it’s also the wrong reaction – China is, after all, a complicated and irreducible country.

Recent events illustrate why this is so. Last week, Xinhua, China’s state-run news agency, reported that Sun Zhengcai, party chief of Chongqing, had been removed from office and replaced by someone loyal to Chinese President Xi Jinping. The report didn’t say that Sun was guilty of anything, but multiple sources have since told Western news outlets like the Wall Street Journal, Reuters and Bloomberg that Sun is being investigated for “serious” violations of Communist Party discipline. While the Chinese government has made no formal statement on the matter, Xi’s chief anti-corruption officer, Wang Qishan, published an op-ed in the People’s Daily the next day excoriating China’s “unhealthy” political culture, despite five years (and counting) of purges under his watch. Like clockwork, the subsequent headlines made Xi and Wang seem all-powerful.

Yet it was not so long ago that headlines painted a very different picture. Before Sun’s abrupt removal, the big scandal concerned Guo Wengui, a prominent Chinese businessman who fled his home country and took to the airwaves to critique China’s government. Guo set his sights on Wang, whose position was believed to be in jeopardy ahead of the upcoming party convention. But then Sun was purged, the story was rewritten, and now Xi and Wang are again paragons of power.

It’s a tired story, so let’s skip to the end: Xi is firmly in control of China. In fact, no one has been more in control of modern China since Mao Zedong. Xi continues to execute his anti-corruption campaign, but at this point it has less to do with purging potential rivals than it does with decking the halls of power with men loyal only to him. There is, by design, no opposition to Xi’s rule. He is unafraid to pursue potentially controversial policies, including economic reform, ahead of the party congress. China has a lot of problems, but revolution doesn’t seem to be one of them.

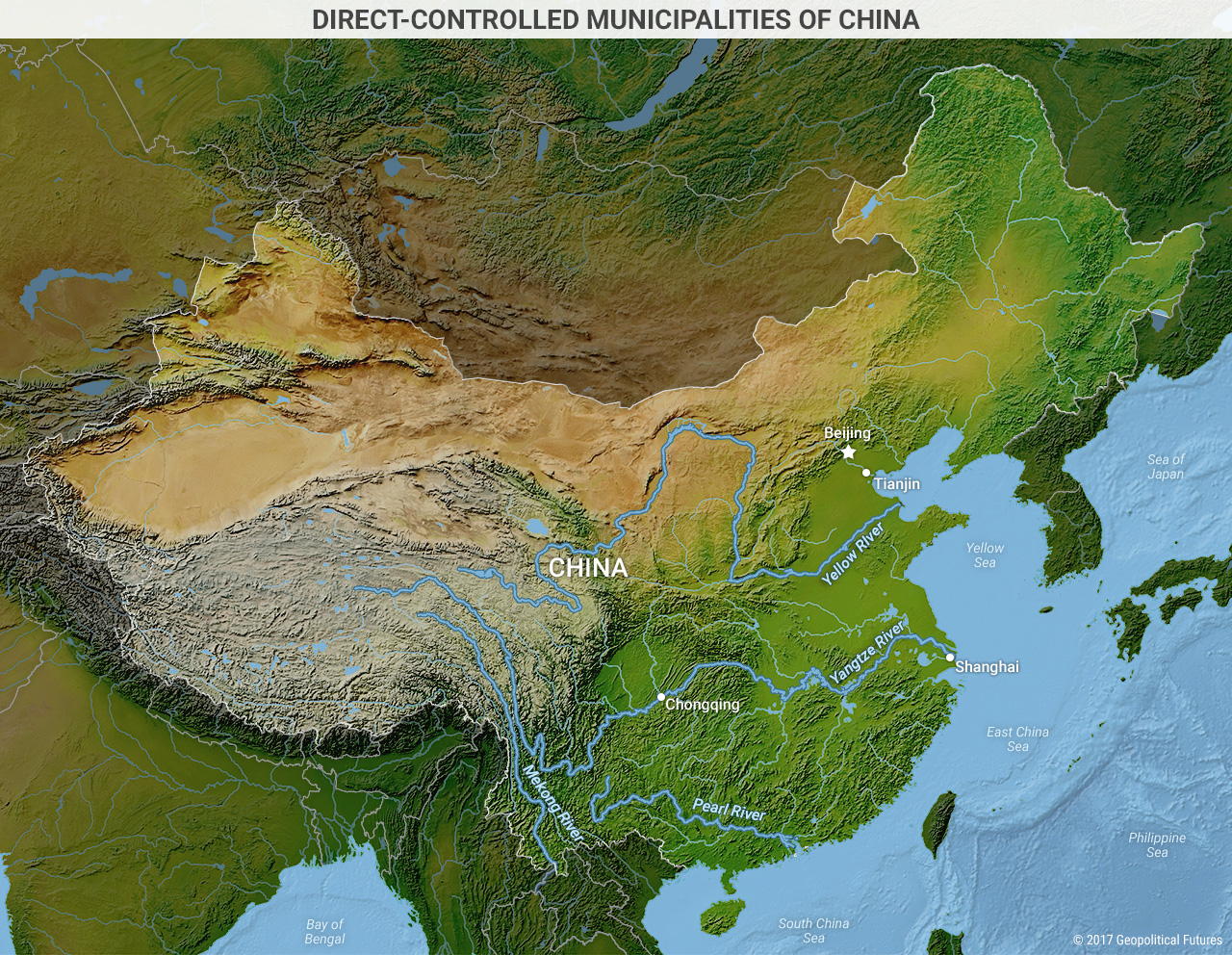

What just happened in China is not nearly as interesting as where it happened: Chongqing. Chongqing is one of four Chinese cities that the central government has seen fit to classify as its own individual province. The others – Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai – are all coastal cities, centers of Chinese wealth and power. Chongqing is an interior city, historically isolated despite its proximity to the Yangtze River and comparatively poorer than cities on the coast. Chongqing has experienced remarkable growth over the past two decades and continues to sport some of the highest regional growth rates in the entire country, but it still lags behind the coastal cities in terms of basic metrics like regional gross domestic product and disposable income levels. According to China Daily, Chongqing needs to continue to grow at current astronomic levels for another three years just to get up to China’s national income average.

The story of Chongqing is the story of modern China. It’s where Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Chinese Nationalists, eventually established his new capital after fleeing the invading Japanese army in 1938. Chiang had little choice in the matter. The Nationalists had no real power base in Chongqing or the surrounding Sichuan area, but they could not fight off the invading Japanese forces on the coast. Chongqing’s isolation and destitution made it an unappealing target for direct Japanese assault. Japan instead opted to wait out the Nationalists, assuming it could take over once the city deteriorated economically. After World War II was over and the Communists won the Chinese civil war, Chongqing was again relegated to backwater status. Years later, when China opened up its economy, successive Chinese governments invented various policies to bring the coastal profits to China’s interior. Chongqing began to blossom. Jiang Zemin called his policy “Open Up the West.” Xi calls his policy “One Belt, One Road.” Both are meant to solve one of China’s most enduring problems: massive social inequality.

But the city is not without problems. Its preternatural growth rates ignore the fact that much of the city’s budget – as much as half in 2012 – comes from the central government. That same year, Xi removed from office a previous party chief of Chongqing, Bo Xilai. Ambitious and charismatic, Bo created what would come to be known as the “Chongqing model,” an economic philosophy that spurred growth through domestic consumption instead of exports – all to ameliorate social inequality. The irony, of course, is that Bo’s reforms are exactly the type of reforms China is trying to implement at a national level today. Bo was removed, not because he was necessarily doing a bad job, but because he became too successful too quickly and because the reforms he authored were associated more with him than with the Communist Party. (He is currently serving a life sentence.)

Sun is not Bo – he has neither the ambition nor the charisma that made a man like Bo so dangerous to the upper echelons of Chinese politics. But there is also no such thing as a coincidence in geopolitics. Sun is the second of the past three people to be removed from this post because of an inability or unwillingness to demonstrate his absolute loyalty to the central government. In itself this is telling.

Sun’s dismissal is not a litmus test for Xi’s power. Chongqing’s status is a litmus test for the viability of the People’s Republic of China. Since it was founded in 1949, China has achieved more than what most could have imagined, but it is still afflicted by problems that cannot be solved by dismissing party officials or by writing heavy-handed op-eds in the People’s Daily. The only way to end this story is to recast Chinese geography entirely.