By Antonia Colibasanu

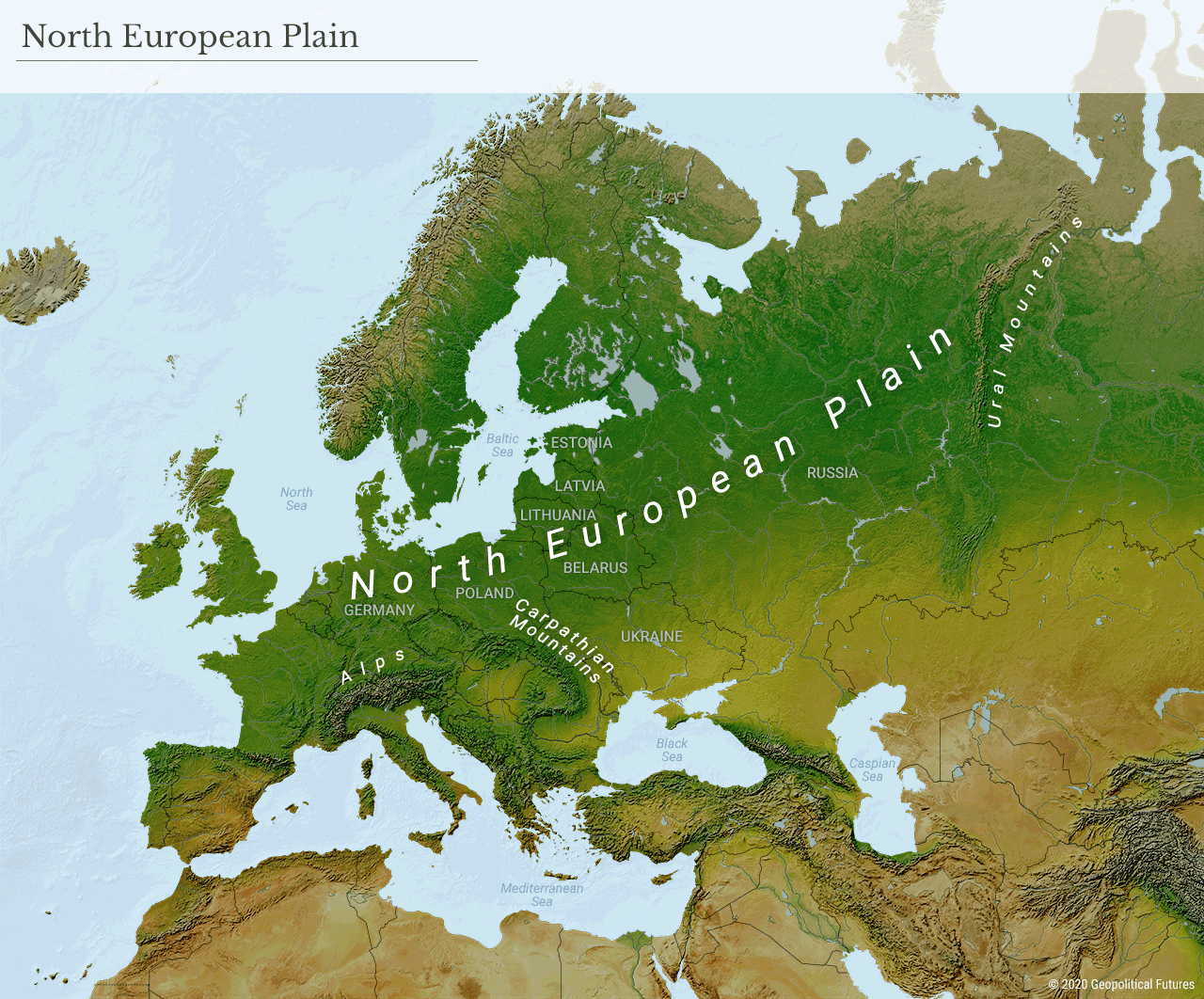

When flying over the vast North European Plain in January, you understand the reasons for Poland’s anxiety when it comes to national security. While the land was covered by snow, I could only think of how vulnerable it looked. There was nothing protecting the soft patches of whiteness in between the gray lines of roads or railroads, as seen from the plane. It seemed that the wind alone could spoil it all in a few hours, as frozen as it was.

Polish President Andrzej Duda (R) and Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko attend a welcoming ceremony at the court of the presidential palace in Warsaw on Dec. 2, 2016. JANEK SKARZYNSKI/AFP/Getty Images

I was on my way to Rzeszów for a conference on the European Union and Ukraine, to discuss and learn about the security and socio-economic challenges in the Eastern European borderlands. We flew for about an hour from Warsaw to Rzeszów, the biggest city in southeast Poland, about 60 miles from the Ukrainian border. This is a place where history reveals the reasons for both Polish pride and fears. During WWI, Rzeszów was one of the towns where the Austro-Hungarians fought the Russian army and were defeated. During WWII, it was bombed by the Luftwaffe and occupied by the Germans, but remained the main center for the Polish resistance movement called the Home Army. Locals always stress that the Home Army was loyal to the British and that during the war, whenever resistance operations were carried out by the Home Army, negotiations with the Russians failed, keeping Rzeszów under German occupation until the end of the war. Rzeszów also prides itself on being the town where Rural Solidarity, the Polish civil resistance movement against the communist government, was established. These are not only historical reasons for national pride but also measures of resistance against Russia. This and closeness to the Ukrainian border makes Rzeszów the perfect place to discuss the challenges Poland faces today.

For Poland, geopolitics is an existential issue, with its national strategy pivoting around a single goal: preserving national identity and independence. Due to its geographic location, situated in the often-invaded North European Plain, Poland has been vulnerable to moves by other Eurasian powers. NATO and EU membership has removed Germany as a potential threat. But, from Poland’s perspective, it is not protected against Russian aggression.

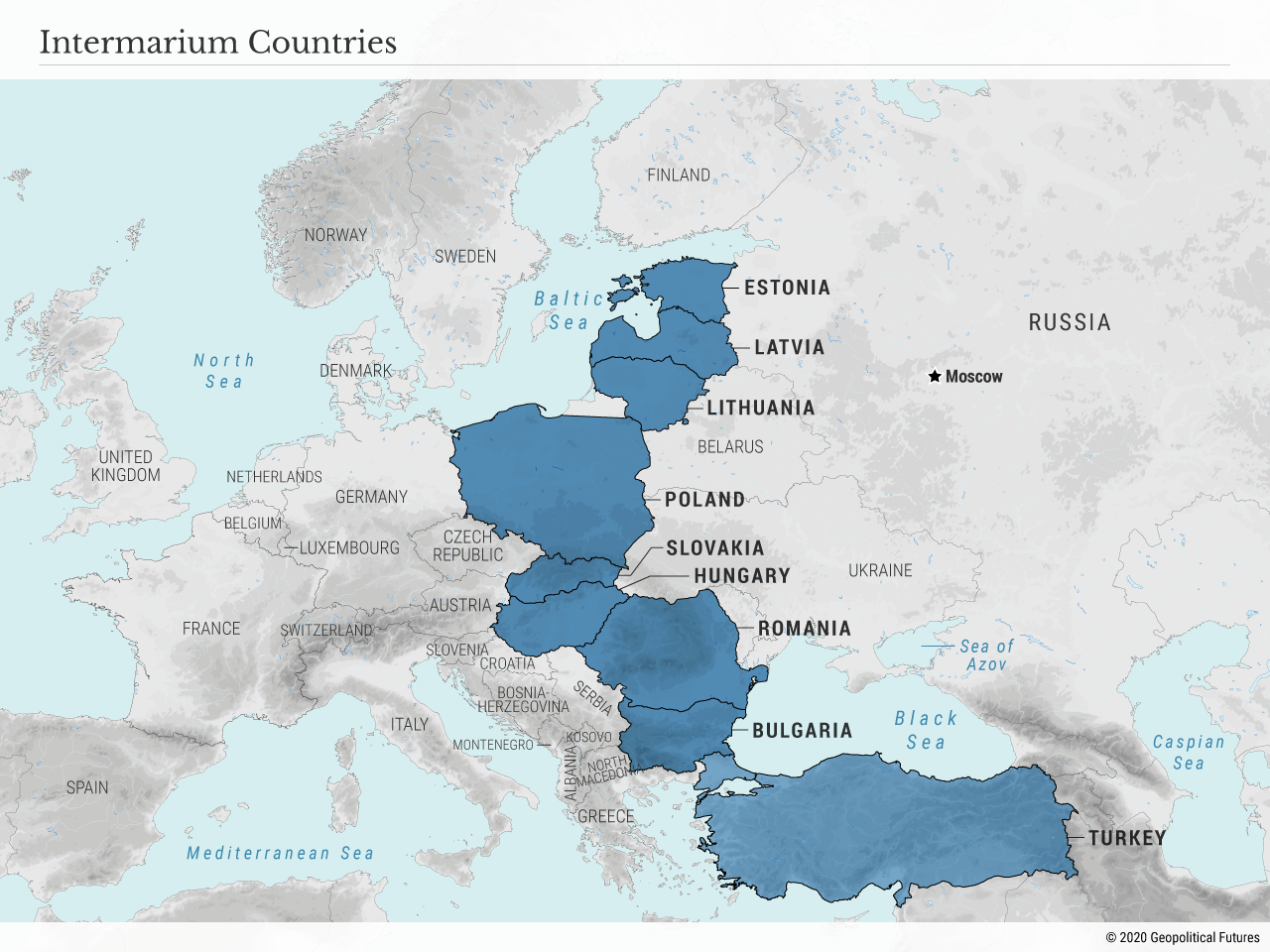

In 2016, the standoff between Russia and the West over Ukraine lost visibility in international mainstream media and slowly evolved into a de facto frozen conflict. Both Russia and NATO have increased their military buildup in the region over the last few months. The Eastern flank, from the Baltics to the Black Sea, saw the biggest NATO deployment since the Cold War. Thirteen countries will contribute to the four battalions to be stationed in Poland and the Baltics, while Romania, Turkey and Bulgaria plan to increase air patrolling and enhance security at the Black Sea starting in 2017. The U.S. has also shown its most significant commitment to the region since the end of the Cold War. But talks during the conference indicated fear of war is not decreasing. On the contrary, among the Europeans, there’s an obsessive repetition of the fact that Russia becomes more aggressive as it weakens internally.

Countries in the north, particularly Poland, have chosen two paths to limit the Russian threat. One is forging defense ties with countries in the region that share similar fears, while closely working with the U.S. This contributes to the Intermarium, the containment line against Russia from the Baltics to the Black Sea. But Poland knows that the West is in no position to fight against Russian influence further east and that NATO and the U.S. are unlikely to react to a potential Russo-Ukrainian escalation. This is why Poland’s second path to limit the Russian threat is to try to keep Kiev closer to Warsaw and the West, challenging Russia’s role in the former Soviet periphery.

Perceiving the increasing Russian threat in Eastern Europe, Poland championed regional cooperation initiatives within and outside the NATO framework before the Ukrainian crisis. Warsaw has worked on increasing cooperation between the so-called Northern Group countries, which include NATO members and non-members. These countries are Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Poland. They have worked on coordinating their technical capabilities so that they can take on common missions. Since 2017, they have agreed on enhanced access to each other’s territory, which would improve the operational effect and quality of air, land and naval operations. Poland’s improved cooperation with Romania resulted in the Bucharest Summit that gathered all of NATO’s Eastern European members ahead of last year’s NATO summit. While coordination between the two has been supported through diplomacy, there’s still room for more effective operational coordination relating to defense and security.

In addition to supporting regional cooperation, Poland has moved to enhance its defense ties with Ukraine. Poland has renewed a bilateral defense agreement with Ukraine, which enters into force in 2017. The official statement on the agreement says that the cooperation relates to both countries’ “military sectors, providing a legal basis for the expansion of cooperation in 24 areas, including virtually all spheres within the scope of the defense industries of the two countries.” The agreement also refers to “the delivery of weapons and military technology and the provision of services of a military-technical nature,” strengthening cooperation between the countries’ defense industries.

This is the first integrative military deal between a NATO country and Ukraine. Kiev needs to improve its defense capabilities – and Warsaw needs to maintain its influence over Ukraine’s military buildup if it wants to make sure Russia does not gain ground there again. Considering the de facto frozen conflict in the east, Poland has benefited from the current pro-Western approach in Kiev and the country’s attempts at reform. Poland initiated the agreement and was willing to offer whatever was needed to make sure the Ukrainian army develops according to Western standards. This included cooperation related to personnel training, consultations, military equipment and armament, liaison organization and logistics.

This integrative approach is also motivated by the fact that Ukraine’s infrastructure – a key factor in the country’s development, including its defense – is currently administered by Polish managers. Poland’s former Minister of Transport Sławomir Nowak was appointed director of the State Agency of Automobile Roads of Ukraine in October 2016. Wojciech Balczun, a successful Polish executive who served in the past as LOT Polish Airlines’ supervisory board chairman and worked with the Polish State Railways and the Polish Tourism Development Agency, has been head of Ukrainian Railways since last April. This is seen as a softer way to build influence in Ukraine, as are economic aid and investment, both of which Poland has supported since the crisis.

Through these steps, Poland has tried to establish a platform to keep Ukraine closer to the West. Warsaw has been a prominent player in the contest between Moscow and the West over the future of Ukraine, initiating the European Union’s Eastern Partnership program, which sought to bring the former Soviet states closer to the EU. But this time, Poland is attempting to lead the way in seeking to keep Ukraine turned westward. Considering that the Ukrainian economy’s poor performance could lead to social problems, which would destabilize the country and increase Russian influence yet again, Poland clearly took on an ambitious task. While it is key for Polish security to have a stable neighbor, it is not something Warsaw can administer alone: Ukrainian will is required. However, as Poland manages its own fears by building its influence and resistance against Russia in its neighborhood, it is behaving more like a rising regional power in Central Europe.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East