By Jacob L. Shapiro

Geopolitical Futures alerted subscribers on Tuesday to unconfirmed reports of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troop movements in northeastern China, near the border with North Korea. These reports remain unconfirmed. When asked if the reports were true, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said, “I am not aware of that.” This is the perfect thing for a spokesperson to say, because it gives plausible deniability if true but doesn’t eliminate the possibility that it is false. As of this writing, a few major Australian newspapers picked up the story without adding new details or corroborating evidence. Everyone is still reading the tea leaves.

The possible PLA troop deployment raises another question. GPF founder George Friedman noted in a Reality Check last week that the U.S. doesn’t want to attack North Korea, so “Plan A is to ask the Chinese to intervene with the North Koreans.” The question is, what can China do to intervene with the North Koreans? It is often assumed that China has significant power over the regime in Pyongyang. Part of the reason for the assumption is that China wants the world, particularly the U.S., to think this. For decades, North Korea has been both a buffer zone and a bargaining chip for China in its relationship with the U.S. But less time is devoted to the question of whether North Korea is as dependent on China as everyone assumes.

Two recent test cases offer a chance to examine this question. The first is Chinese imports of North Korean coal. U.N. Resolution 2270, passed on March 2, banned the import of North Korean coal. China says it is abiding by this resolution. Reuters reported on April 11 that China was turning away North Korean cargo ships and returning coal shipments to North Korea. Last month’s U.N. resolution came a few months after another U.N. resolution last November put a cap on imports of North Korean coal. The Chinese claimed to abide by that resolution, too. The possibility that China is lying cannot be completely dismissed. But all signs seem to indicate China is enforcing these sanctions in good faith.

A big deal has been made of this, because if you are selective with the facts that you use, it is possible to make North Korean coal exports sound like a bigger deal than they are. North Korea lends itself well to this kind of selective choice of data, partly because of how hard it is to get data on North Korea in the first place. All of the following figures must be taken with a grain of salt, even if the sources are usually trustworthy. The notion that China’s ceasing imports of North Korean coal would be a major blow to Pyongyang is based on the idea that coal is North Korea’s most important export. And by all accounts it is. According to International Trade Center estimates, coal accounted for about 35 percent of North Korea’s exports in 2015. China accounted for about 92 percent of those exports.

The problem with this argument is that it overstates the extent to which the North Korean economy depends on exports. Estimates on North Korea’s GDP range from about $16 billion (U.N. figures) to $30 billion (Bank of Korea figures), which means that the percentage of North Korea’s GDP from exports could be anywhere from 10 to 20 percent. That, in turn, means that coal accounts for between 5 and 7.5 percent of North Korea’s GDP. That is not an insignificant chunk of the North Korean economy, but it is not a big enough lever to control a regime in Pyongyang that has succeeded in shutting off its population from the world and survived famines and economic catastrophe far worse. The threat of China signing on to the coal sanctions was a more effective tool than its implementation. If coal were so important, North Korea would not have felt it could carry on with nuclear tests without batting an eyelash.

The sun rises over the banks of the Yalu River in the Chinese border town of Dandong, opposite the North Korean town of Sinuiju, on Feb. 9, 2016. JOHANNES EISELE/AFP/Getty Images

Food is another main lever that is used to measure China’s real influence over North Korea. One way to gauge the importance of food and evaluate its power as a tool is to look at food aid to North Korea. The U.S. used to provide a significant portion of that aid. According to the Congressional Research Service, between 1995 and 2008, the U.S. accounted for 50 percent of North Korea’s food aid. The U.S. halted this aid in the spring of 2009, after North Korea expelled nuclear inspectors and tested both a missile and a nuclear device. China stepped in, and in 2012, provided almost two-thirds of all food aid given to North Korea, according to the World Food Program (WFP).

Unfortunately, the WFP’s Food Aid Information System, its more comprehensive database, only has data that’s current until 2012. What we do know from the available data is that the WFP is still active in North Korea. Its most recent update said that WFP distributed 1,504 metric tons of food in North Korea last February. This does not include all the food that North Korea imports. But it indicates that China is not North Korea’s only source of food. Ascribing too much importance to food also dismisses the resilience the North Korean regime has shown to previous food crises. For all the speculation about internal power struggles in Pyongyang, there is not much evidence to suggest North Korea has lost any of its resilience.

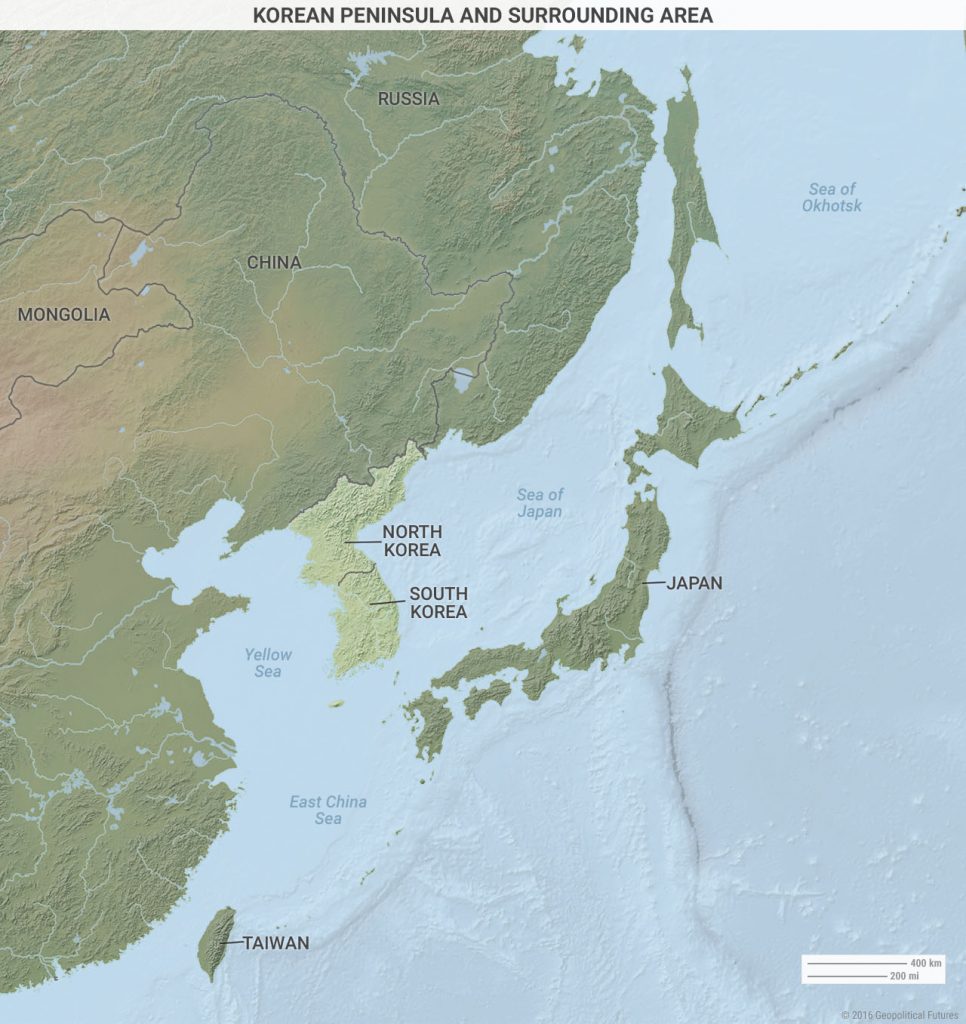

Even if food were a more effective lever than coal, it is limited in its application and effects. At least from China’s perspective, it might create a more problematic situation: Instead of compelling North Korea’s compliance, it could destabilize the regime’s control over the country. One possible explanation for the activation of PLA troops on the border with North Korea is that China is preparing for the fallout of a potential U.S. strike and the humanitarian spillover that could result. China does not want millions of starving North Koreans desperate to cross the Yalu River. It wants to preserve North Korea’s independence and its pro-China posture. Starving the North Korean population into regime change introduces a number of potential scenarios that puts these two imperatives at risk and limits China’s ability to attempt to manipulate it.

The current model under which GPF is operating is that China is using the situation in North Korea to even the playing field in its relationship with the United States. It would make sense that China would want to appear to confront North Korea, and in doing so, get North Korea to back down. At that point, the U.S. would be grateful and would owe China something in return, though the “something” is currently undefined. Some have suggested that what China might want in return is a concession over Taiwan. But that overestimates China’s position in the relationship. President Donald Trump could have turned to President Xi Jinping during the soup course of their dinner last week and said that in return for China’s help on North Korea, his administration wouldn’t go out of its way to block the 20 percent of China’s exports that go to the U.S. market.

This is a dangerous game for China, and it goes directly to the question that began this piece: Just how much control does China have over what is going on in Pyongyang? What the U.S. needs is verifiable proof that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s regime is not building a deliverable nuclear weapon. If this is an elaborate game of good cop, bad cop, China should be able to accommodate, if not publicly, then behind closed doors. But that, in turn, rests on the sanity of Kim. His grandfather was the “The Great Leader,” and his father was “The Dear Leader.” If Kim is “The Crazy Leader,” then coal and food certainly won’t be enough to get him to turn back from the nuclear path his regime has currently taken. The question then becomes what kind of intelligence does China have on North Korea’s nuclear program? Or what kind of assets does it have in country to either control or replace Kim with someone who does not draw the current levels of U.S. attention to the situation?

China wants to be seen as a great power. To do that, it must show that it can exercise power, which narrowly defined is the ability to make another person or country do what you want, even if they don’t want to. Whether it was by design or not, the North Korea gambit has worked in that it has created leverage for China with the U.S. But to capitalize on that, China needs to show that it has the power to rein North Korea in. The unsubstantiated story of troop movements may end up being a rumor, or it may end up being true. Either way, China has taken a seat at the major powers’ table and has been dealt a hand. Now it’s time to see whether China was bluffing.