By Jacob L. Shapiro

For years, Israel and Iran have attacked each other with words and through their proxies. In Iran, calls for Israel’s destruction are routine, and support for militant groups in Syria, Lebanon and the Gaza Strip intentionally challenges Israel’s security. For Israel, meanwhile, “the year is 1938 and Iran is Germany.” Those are the words of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the second-longest serving leader in the country’s history. He has held his position for so long in part because of his ability to convince Israelis that he is best suited to lead Israel in this existential battle with Iran.

It is not surprising, then, that this past weekend’s events seem like a watershed moment. On Feb. 10, an Iranian drone crossed into Israeli territory and was shot down. Israel responded to the Iranian incursion by dispatching fighter jets to attack targets in Syria, including the Tiyas air base, near Palmyra, where the Iranian drone reportedly took off from. Syrian anti-air systems retaliated, striking an Israeli F-16, which crashed after making it back to Israeli territory. This prompted Israel to hit eight Syrian targets and four Iranian positions, according to the Israel Defense Forces. The war of words and proxies seems to be turning into a war between nations.

Lost in this sequence of events is the broader context. Israel is not the only country to have military aircraft shot down by enemy fire in Syria recently. Last week, Russia intensified airstrikes in Idlib province after al-Qaida-linked militants brought down a Russian fighter jet. On the same day the Israeli F-16 went down, Syrian Kurdish fighters reportedly brought down a Turkish military helicopter that was part of Turkey’s invasion of northern Syria. Israel, Russia and Turkey all lost military aircraft during operations in Syria in the past week, and all three are currently working at cross purposes. The Israel-Iran showdown is about far more than just Israel and Iran. It is one aspect of a much larger war for regional power that is being waged more openly with each passing day.

Hazy Alliances

Last week’s crucial developments were not confined to downed military aircraft. On Feb. 6, pro-Assad forces attacked Turkish military forces attempting to set up an outpost close to the city of Aleppo. Some sources reported that an Iranian-backed militia was also involved in the attack. Just two months ago, Turkey and Iran were coordinating a cease-fire in Syria. Now, they are at each other’s throats.

Then on Feb. 7, pro-Assad forces attacked the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces in eastern Syria, resulting in U.S. airstrikes. Just two months ago, pro-Assad forces and the SDF were coordinating an offensive against the Islamic State. Now, they too are at each other’s throats. The war in Syria has become more than simply a civil war; it is now a regional war featuring Israel, Iran, Russia, Turkey and the United States.

If this seems confusing, that’s because it is. Allegiances are in a constant state of flux, dependent more on what various sides can do for each other in the short term than on long-standing arrangements or promises of trust. Consider that the U.S.-backed SDF, made up primarily of Syrian Kurdish fighters, is cooperating with the Assad regime so it can send reinforcements into Afrin to combat Turkish troops. In effect, the SDF is cooperating with Assad in one part of Syria and coming under attack from Assad in another part of Syria. Consider too that Turkey, officially part of a tripartite agreement with Russia and Iran to bring an end to the Syrian war, has invaded Syria to protect its interests from Russia and Iran, and yet it is equally hostile to Russia and Iran’s main enemy, the United States, because the U.S. is providing support for Syrian Kurds. The only thing that is certain in this conflict is that no alliance is certain.

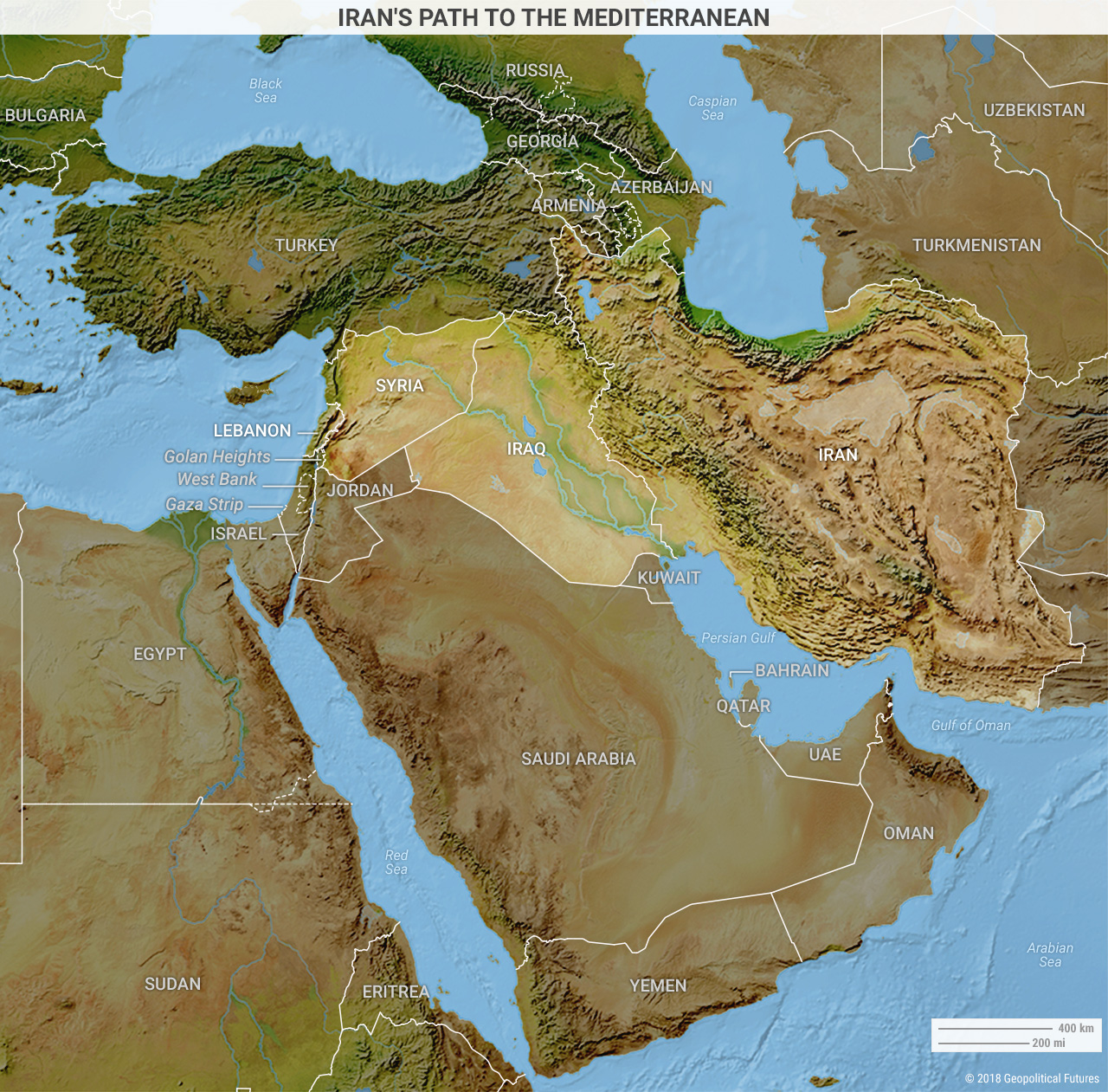

Hazy as these strategic arrangements are, they all boil down to one thing: Iran’s attempt to take over Syria. Turkey talked about its invasion of northern Syria for over a year, and its troops entered Afrin with great media fanfare. But while Turkey was talking, Iran was actually doing. Since the Syrian civil war started in 2011, Iran has been dispatching soldiers, militias, money and weapons to support the Assad regime. The result has been the transformation of Syria from an authoritarian military dictatorship friendly to Iran to an Iranian proxy in desperate need of Iranian support just to stay alive. For Iran, that is a massive strategic opportunity: It can make its continued support of Bashar Assad contingent on Assad’s allowing Iran to do whatever it wants in Syria. And what Iran wants in Syria is a forward base into the Levant.

That is what has Israel so nervous. Despite all the rhetoric, Israel and Iran haven’t fought a war against each other because there is no way for Israel and Iran to fight a war. They are too far apart. That would no longer be the case if Iran can make Syria a staging ground for Iranian attacks against Israel. It is one thing for an Iranian proxy like Hezbollah, with its limited number of fighters, to fire rockets at Israel from Lebanon. It is quite another thing for Iran to start building missiles, massing ground forces and stationing aircraft in Syria, just across the Israeli border. To make matters worse for Israel, it has no comparable position on the Iranian border. Even if it did, Israel cannot expend soldiers the way Iran can in a protracted conflict. For Israel, Iran’s nuclear program is concerning, but Syria as a base of Iranian operations is a mortal threat.

Israel’s Advantages

Israel has a few things going for it, though. The Assad regime is not dependent on just Iran but Russia too, and Moscow has no interest in Syria becoming an Iranian protectorate. Russia wants to preserve Syria as an independent actor and a Russian ally, not as a part of Iran’s plan to project power throughout the region. The Tiyas air base, which was the target of the Israeli strike over the weekend, has also been a base for Russian aircraft in Syria. Russia and Israel have close relations – Netanyahu was in Russia just last month to express Israeli concerns to Moscow – and Russia is not looking to pick a fight with Israel. Israel may not be able to fight a conventional war against Iran, but the Israeli air force is without peer in the Middle East – and that includes Russia’s aerial presence. Furthermore, the U.S. has Israel’s back on this one. It doesn’t want Iran in Syria any more than Israel does. The Russian-Iranian marriage of convenience will fracture the more ambitious Iran gets.

Iran’s moves in Syria also directly threaten Turkey, which also has no desire to see Iranian bases on its border. The more Iran engages in Syria, the closer it pushes Israel and Turkey together. Ties between the two have been strained since the Mavi Marmara flotilla incident in 2010, but the real reason Israeli-Turkish relations are tense is that Turkey’s position in the Middle East has changed. It went from being a dependable U.S. and NATO ally to a powerful nation-state concerned primarily with securing its own interests, which Israel must view with inherent suspicion. That said, both will see eye to eye on limiting Iran in Syria. If Israel comes to believe Russia is not doing enough to rein Iran in, it will also not hesitate to deepen coordination with Turkey, which would be disastrous from Moscow’s perspective. It would also align with our 2018 forecast.

Last but not least is that the majority of the region’s powers are hostile to Iran. Notably absent from the recent developments in Syria is Iran’s most vociferous enemy, Saudi Arabia. The Saudis, who as recently as November were threatening war against Iran, have fallen eerily silent. But make no mistake: Saudi Arabia remains extremely antagonistic to Iran and will support Israeli moves against it (and Saudi Arabia, unlike Israel, is within range of Iran). In addition, Egypt and Jordan remain aligned with Israel. Egypt invited Hamas leaders to Cairo for a meeting this past weekend, perhaps to let them know that their recent willingness to mend relations with Iran is a nonstarter.

Iran is attempting to take control of Syria. Israel does not want that to happen. Israel has been bombing targets in Syria for years to prevent it from happening. It will continue to do so. But Israel’s future depends not on its bombs but on its ability to position itself within a regional coalition that opposes Iran’s ambitions for power. The outline of that coalition is beginning to take shape: The interests of Israel, Turkey and the Arab states are converging. In a sense, Iran is now in the position the Islamic State was mere months ago. The Islamic State’s emergence created strange bedfellows, all of whom cooperated to ensure its demise. Now Iran is seeking to fill the power vacuum left behind by the Islamic State’s defeat. The responses, of which Israel’s attacks over the weekend are just one example, show why in the long term Iran’s gains are likely to be ephemeral. In the short term, however, Iran will press its advantage. The war in Syria has only just begun.