By Jacob L. Shapiro

It’s been a busy week for Indian foreign policy. In the past, that statement would have been an oxymoron. The Himalayas isolate India from developments in the rest of the world. Internal diversity makes it hard for India to govern itself, let alone to influence others (though the irony of an American writing that a few days after the U.S. government shutdown is not lost on me). The scope of India’s poverty makes China look like a uniformly rich society by comparison.

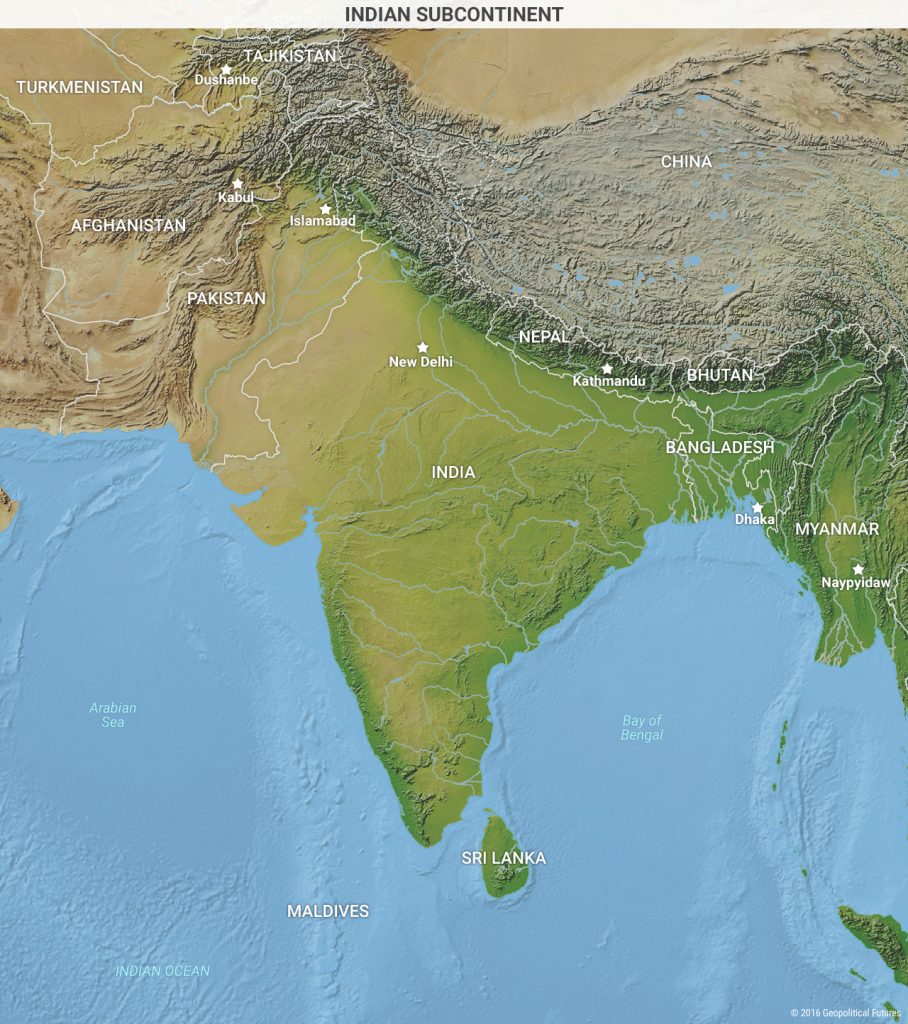

For all these reasons, India has been a minor player on the world stage in modern history. India was the “jewel in the crown” of the British Empire, a vast land of resources for the British to appropriate. The British controlled India not so much by force as by playing its diverse groups against each other. After the British left and an independent India emerged, India was a relatively insignificant actor in the Cold War, engaged in a nuclear arms race with Pakistan and fought a few skirmishes with China. Overall, though, the impact of India’s actions was confined to the Indian subcontinent.

But now India has arrived at an unprecedented moment in its history. At home, the Bharatiya Janata Party, with its clear vision of what a united India’s interests are in the world, is in a strong position. Abroad, fear of China’s heavy-handed attempts to gain influence have many looking to India as, if not a savior, then the only counterweight to China’s demographic, economic and military heft. India is trying to make the most of this chance. Even so, the reason many Asian countries trust India to counter China is because they do not think India is as great a threat to them as China because of its fundamental weaknesses. India is limiting China at the invitation of others.

An Alternative to China

Most foreign media this week focused on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s rousing introductory speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos and on the renewed competition between China and India around Doklam. These issues aren’t especially important. Davos is a nice conference for world leaders to enjoy themselves while accomplishing nothing that will have much effect on the world. In Doklam, the geography makes the prospects of an India-China war remote at best. If China and India were to fight over a disputed border region, it would be in Nepal or Tibet; Doklam is political grandstanding.

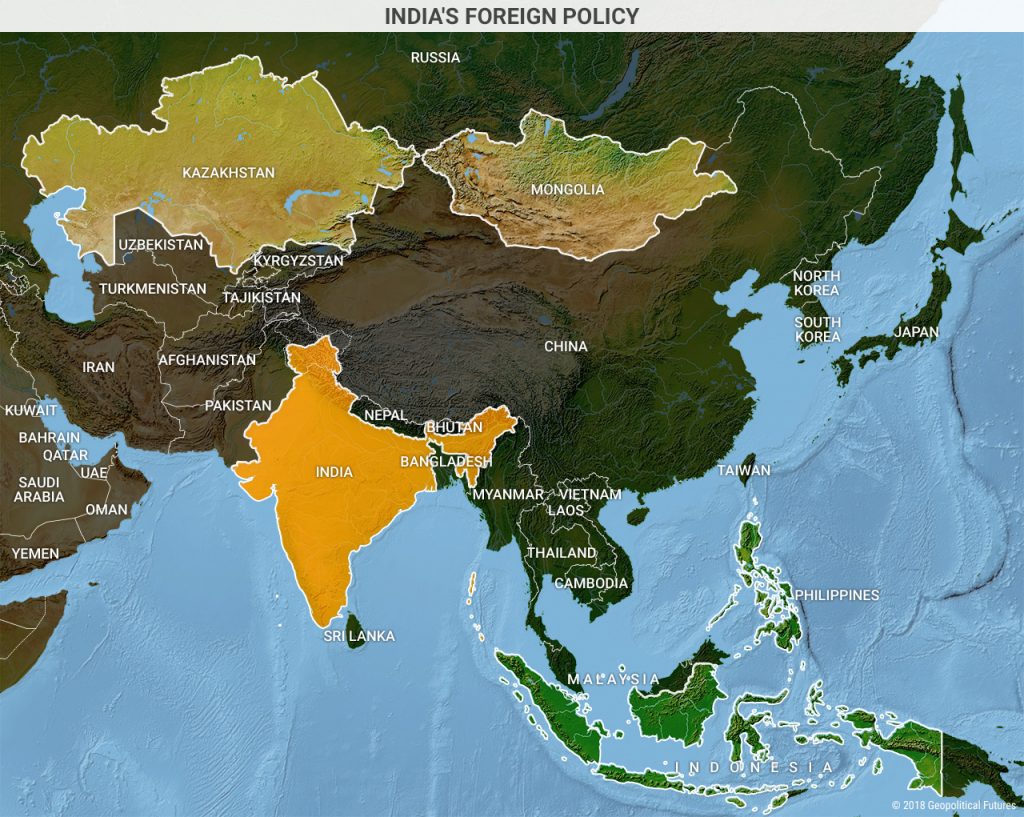

And there are other, more consequential areas that India is seeking to make its presence felt than Davos and Doklam. The first is in the vast buffer region between China and Russia. China covets this area, which is made up mostly of Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Beijing’s One Belt, One Road initiative is, at its core, a strategy for China to develop new markets for its excess supply of goods and raw materials and to build the prosperity of China’s vast, impoverished interior. China’s investment, however, often comes with strings attached: Chinese workers, or preferential arrangements for Chinese companies. These are strategic areas of the world that China wants to influence and even control.

India is far less ambitious. Its goals are to make money and thwart Chinese plans, which it can do merely by offering an alternative to China. On Jan. 24, the Mongolian government announced that construction on the country’s first oil refinery would begin in April – funded by India in a deal reached in 2015. Meanwhile, on Jan. 25, Kazakhstan announced plans to implement visa-free 72-hour transit for Indian citizens. Kazakhstan debuted this pilot visa regime with China, and a Kazakh government official noted that the arrangement was so successful at attracting Chinese investment that the country decided to extend it to India as well.

The same dynamic applies to Southeast Asia, where China has also pushed its One Belt, One Road initiative. For China, the most important country in the region is the Philippines because a close relationship with Manila would give Beijing access to the Pacific. India is active there too. A Philippine government official said Jan. 23 that India had pledged over $1.25 billion in investment for 2018, money that is expected to create more than 100,000 jobs in the country. For perspective, in 2016, $1.25 billion would have made India the second-largest foreign investor in the Philippines, behind the Netherlands and immediately ahead of the United States, Australia and China.

In Southeast Asia, though, India has greater ambitions. On Jan. 25, India hosted the leaders of all 10 countries that make up the Association of Southeast Asian Nations to promote “maritime security” in the region. The day before that, India announced that it had agreed with Indonesia to increase bilateral defense cooperation through joint exercises, arms deals and high-level visits of officials. This is in addition to India’s recent support for the resurrection of the Quad, an amorphous alignment of India, Japan, Australia and the U.S. whose chief goal is to limit Chinese expansion, and India’s more liberal deployment of its naval forces for military exercises on the Pacific side of the Indo-Pacific.

Dose of Reality

All this sounds impressive, and on a certain level it is, especially for a country with a history of global involvement like India’s. But these developments should not be oversold. India is hosting ASEAN leaders and throwing investment money around the region, but China’s clout is still overwhelming by comparison. China accounted for 14 percent of total ASEAN trade in 2014 and 15.2 percent in 2015 (the latest year for which stats were available). India, on the other hand, accounted for 2.7 percent in 2014 and 2.4 percent in 2015, meaning that not only is India’s share of ASEAN trade much lower than China’s, but it is decreasing. In the long term, India may well provide a balance for some of these countries, but they need a counterweight to China now, and India’s ability to help is limited.

In the past week, there was also an internal development that underscores India’s geopolitical handicap. Shiv Sena, an important political party in India’s western state of Maharashtra, announced Jan. 23 that it was breaking with the BJP in upcoming general and state elections. Shiv Sena has not indicated that it plans to withdraw from India’s coalition government, and by all accounts the breach is not ideological but political. The party supports the BJP’s vision of a united, Hindu India, even if it did not appreciate the way the BJP took Shiv Sena’s support for granted. But the deeper issue is that Shiv Sena started not as a Hindu nationalist party but as a pro-Marathi party. (Marathis are the dominant ethnic group in Maharashtra.)

Shiv Sena is not returning to its pro-Marathi roots – or at least it’s given no indication that it will. But its break with the BJP underscores just how fleeting the BJP’s level of control is. India is, after all, a democracy, and the BJP government is as susceptible to being voted out of office as any political party is in a democracy. The BJP has consolidated power at home and projected power abroad because of its strong political position, but nothing says that position must be permanent. Beneath the veneer of strength of the BJP’s governing coalition are the divisions that the British used to control India, the same divisions that have long prevented India from harnessing its demographic and economic potential.

In a sense, India’s foreign policy is still passive. The hallmark of power is not that countries will take your money and use it to build refineries, or that foreign leaders will visit and eat your food at interesting summits about maritime security. The real test of power is whether a country can make other countries do what it wants. And for all the activity involving India this past week, none of it suggests that India is amassing that kind of power. Instead, India is thwarting Chinese power. It is doing this because it wants to, but more than that, because other countries want it to. India is playing on the world stage, and that is notable – but it is playing at the invitation and with the blessing of others. It is not master of its fate.