By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Nov. 22, an economist wrote in a Russian-language newspaper: “To judge by the flood of complaints, guarantees on bank deposits are ceasing to operate. People are often paid a fraction of their deposits and are being told that before closing the bank destroyed its documents, and your copies of the contracts are not binding for us!” (Translation by the BBC.) The article was not about banks in particular, but rather about the potential for early presidential elections in Russia in the spring of 2017. It was another in a series of speculative articles that have appeared on the same topic. But the line in the middle of the story about banks stands out and warrants further investigation, because it raises serious questions about the current state of the Russian banking system and, more broadly, the Russian economy.

The article appeared in Moskovskij Komsomolets, a well-known newspaper with a circulation of roughly 700,000, mostly in Moscow. The author served in various political capacities, most notably as former chairman of the Rodina party’s ideological council from 2004 to 2006. The party, also known as the Motherland-National Patriotic Union, had many founders, but the most well-known is Dmitry Rogozin, Russia’s deputy prime minister since 2011. The party’s slogan in the mid-2000s was “For Putin, Against the Government.” The article’s tone is consistent with that message. It is critical of forces in the Russian government that allegedly sabotaged President Vladimir Putin’s economic goals, and claims that fresh elections would shake up the system. That shake-up would leave Putin with a freer hand as elder statesman instead of president. The article also references comments made earlier this month by a political analyst working for the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, which suggested Putin may “have to be absent from the public space for several months” in 2017.

Russia’s Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA) was established in 2004, and while its primary function is to make payments to depositors following bank failures, it has in recent years added the responsibilities of overseeing bankruptcy proceedings to liquidate insolvent banks and serving as the system administrator of Russia’s mandatory pension system. Since late 2014, the DIA has insured deposits in Russian banks of up to 1.4 million rubles, roughly $21,000 at current exchange rates. Many Russians don’t put savings of that size into bank accounts. A 2013 countrywide study sponsored in part by Russia’s Ministry of Finance found that of 6,103 households surveyed, only 45.1 percent reported having savings, and the average balance of a household’s bank accounts was about 218,000 rubles. But that doesn’t make the potential destabilizing effect of a failure of the Russian banking system any less serious.

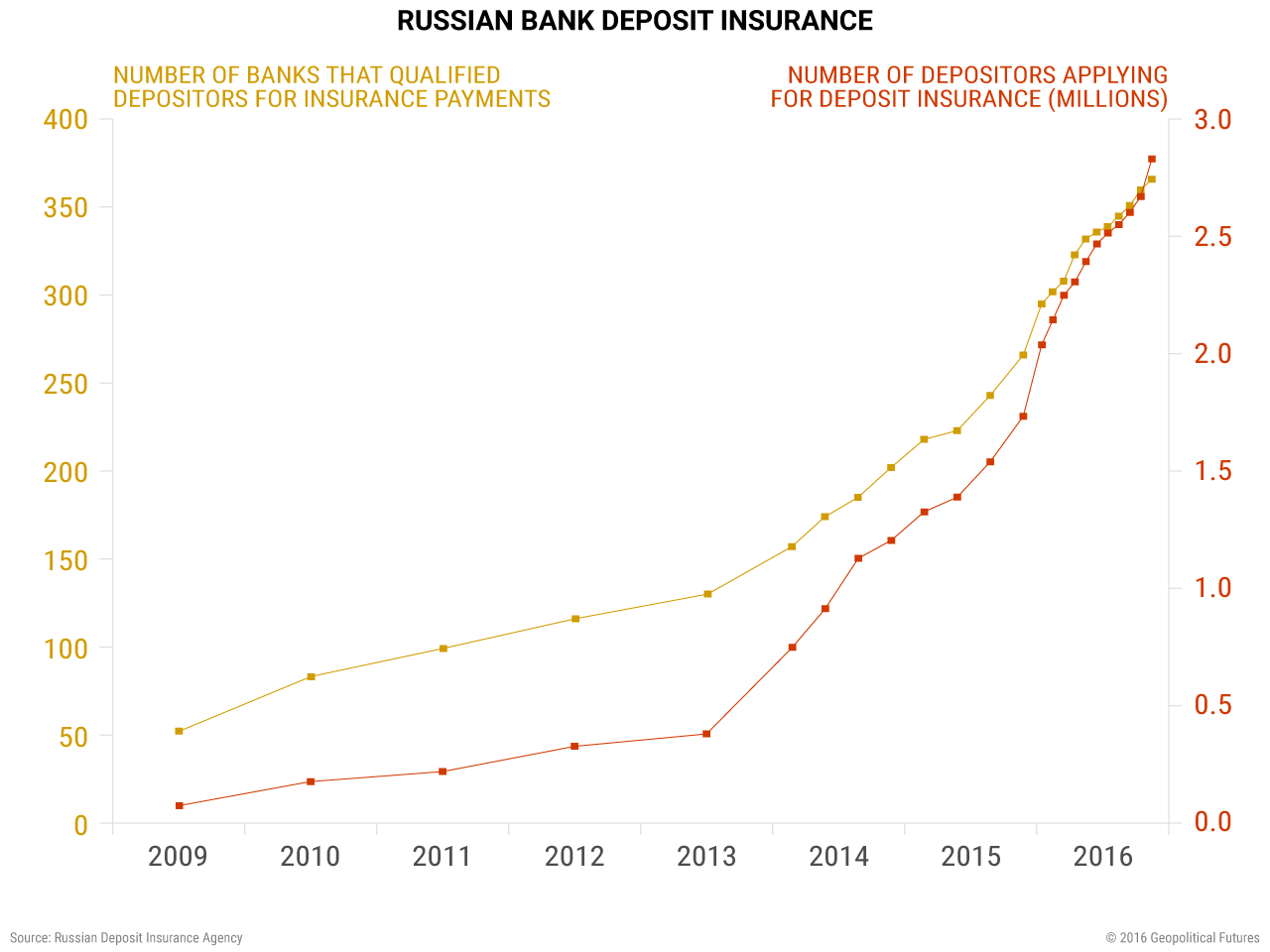

The above graph was made with statistics from the DIA. The numbers correspond with what one would expect from an economy dependent on oil exports. Russia has been under severe economic strain since oil prices collapsed in 2014, and sanctions imposed by the United States and European countries have dried up foreign investment into Russia as well as important sources of capital. In the first decade of the DIA’s existence, 157 banks had what the DIA deems an “insured event.” In simpler terms, the DIA compensated depositors for losses 157 times. In roughly the last three years, that number has increased by 209. From 2004 to 2009, 72,400 people applied to the DIA for deposit insurance compensation. As of the beginning of this month, 2.7 million more depositors have applied since then.

According to the DIA’s website, a depositor is entitled to receive compensation in two situations. The first is when the Bank of Russia decertifies an individual bank’s license, which halts that bank’s ability to engage in banking transactions. The second is when the Bank of Russia introduces a “moratorium on satisfaction of creditors of the bank.” This is where details of what really is happening become hard to discern, because Russian deposit insurance kicks in not just in cases of bank failure, but also in cases of bank decertification. Russia’s Central Bank has decertified 24 banks since the start of the year. Moscow-based Arksbank’s license was revoked on July 19 for what the central bank characterized as “aggressive policies to attract deposits,” as well as a lack of adequate capital provisions for current investments. DIA characterized Arksbank’s activities as “fraud,” and said in a Nov. 23 statement that of 39,810 depositors, 37,044 had been compensated.

Two other cases present similar difficulties for analysis. On Nov. 3, the central bank revoked the license of Kamskiy gorizont bank, located in the Republic of Tatarstan, in Russia’s Volga Federal District. The central bank said Kamskiy gorizont had violated laws related to money laundering, and bad practices led to the loss of the credit organization’s own funds. According to the DIA, it began distributing insurance deposits on this case on Nov. 17, though it is unclear when all depositors will be covered. Peresvet Bank, headquartered in Moscow, is another example. The DIA announced on Nov. 3 that it would begin insurance compensation of the bank’s depositors by Nov. 7, because the Bank of Russia on Oct. 21 issued a moratorium on satisfaction of creditors’ claims. Peresvet, which is 49.7 percent owned by the Russian Orthodox Church, reappeared in the news a few weeks later when Kommersant reported on Nov. 15 that the central bank had presented a proposal to Persevet’s creditors to save the bank by providing it with 106 billion rubles ($1.62 billion). The plan also reportedly called for a bail-in mechanism, though the precise details at this point are unclear.

A police officer guards the entrance to the head office of Russia’s Central Bank in Moscow, on Dec. 17, 2014. YURI KADOBNOV/AFP/Getty Images

Two distinct possibilities could explain the situation. It is possible that Russia is cleaning up its banking system by shutting down banks engaging in illegal or irresponsible activity. This could be taken as a sign of health for Russia’s banking system and might justify some of the optimism in recent statements by the International Monetary Fund and Russian government that the country will return to growth in 2017. The central bank’s governor has said the banking sector may have an aggregate profit of 500 billion rubles ($7.9 billion) by the end of 2016. But it is also possible that underneath the rules and regulations, Russia’s banks are hurting far more than Putin and the Russian government want to admit. Relying on deposit insurance could be seen as an extreme measure of last resort. It would make the fact that the resources of the DIA’s Mandatory Deposit Insurance Fund have decreased by over 75 percent in the last two years particularly concerning. That some are complaining about not receiving payments of guarantees on bank deposits would be even more ominous.

Our model says Russia’s economy will continue to struggle, and there is no relief coming next year. The one thing Russia needs is higher oil prices, and it does not appear it will get them. If Russia’s banking system is in more serious distress than authorities are admitting, it puts Putin in a very difficult position, and perhaps explains some of the rumors of political machinations and early elections. Russia could theoretically print more rubles, but this time last year inflation in Russia was at 15 percent. Russia has worked hard to get that figure down to 6.1 percent as of last month. A further weakening of the ruble is not something Putin wants in the lead-up to elections, whether they happen in 2017 or 2018, as planned (and as Kremlin spokesmen have steadfastly insisted). A string of bank failures is no more appealing. Ultimately, it is necessary to conclude that while we have our suspicions, there isn’t enough evidence yet to prove them. That isn’t normally how we do things, but this issue is important enough to raise the possibilities, and to inform our readers that we will continue to look closely for evidence in coming weeks and months to ascertain what is true.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President