By Kamran Bokhari

There is a growing expectation these days that the caliphal regime of the Islamic State will collapse. The disproportionate focus on this desired outcome obscures the fact that even when this happens the specter of jihadism will continue in Syria in the form of many other groups. Key among them is al-Qaida, which has quietly been working to take advantage of the mainstream rebels’ weakening at the hands of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime and the international efforts to neutralize IS. While sharing the same goal and (more or less) the same ideology, al-Qaida and IS are bitter competitors for the leadership of the global jihadist movement whose rivalry will shape the future course of transnational jihadism.

Two suicide bombers detonated bombs in Damascus on March 15, targeting a main judicial building and a restaurant, killing dozens and injuring nearly 150 people. On March 12, another suicide bombing at a Shiite shrine in the Syrian capital claimed 80 lives. In recent years, IS has carried out such attacks. However, both these attacks have been claimed by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (Committee for the Liberation of the Levant), the third and most-recent incarnation of the group formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian branch of al-Qaida.

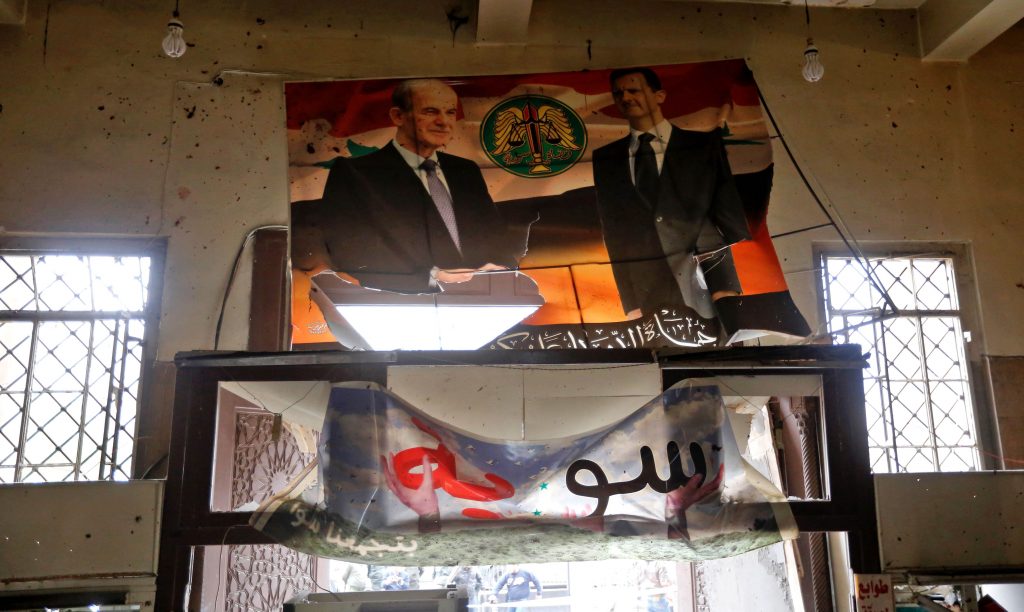

Portraits of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, right, and his late father and former President Hafez al-Assad are seen inside the old Palace of Justice building in Damascus, following a reported suicide bombing on March 15, 2017. Two suicide bombings hit Damascus including the attack at the central courthouse that left at least 32 dead, as Syria’s war entered its seventh year with the regime now claiming the upper hand. LOUAI BESHARA/AFP/Getty Images

Bombings in Damascus are rare, and in the last three days two major attacks have occurred. This means that al-Qaida’s Syrian ally has developed the capability to penetrate the Syrian regime’s best possible security arrangements to strike in the capital. This may sound surprising but only to those who have not been paying attention to al-Qaida’s moves in the country. While the world’s attention is focused on IS, especially as it loses its largest urban center in Mosul and expects an assault on its capital Raqqa, al-Qaida has been quietly preparing to assume a lead role in the evolving Syrian battlespace, particularly IS’ downfall.

Not too long ago, both groups were part of al-Qaida’s global jihadist network. In 2012, IS – then called the Islamic State of Iraq – was on a path toward resurgence in Iraq in the aftermath of the departure of U.S. troops in December 2011 amid renewed Shiite-Sunni polarization. That same year, al-Qaida, taking advantage of the Syrian civil war, was able to establish a branch called Jabhat al-Nusra in the Levantine country. From al-Qaida’s point of view, these were two separate branches that reported back to the global leadership based in northwestern Pakistan.

By then, the apex al-Qaida leadership had been sufficiently weakened, especially with the May 2011 killing of its founder, Osama bin Laden, at the hands of U.S. Navy SEALs. Since 2003, al-Qaida had been on a steady decline, and its leadership had traded operational control of the international jihadist movement for personal security of its top leadership. This led to the effective operational independence of the various geographic nodes of al-Qaida. The most significant was the Iraqi node, which emerged as the most powerful al-Qaida branch given the anarchy that prevailed in Iraq in the eight years after the U.S. attempt to effect regime change, which unleashed the torrent of the Shiite-Sunni conflict.

By the time the Arab Spring uprising turned bloody in Syria, the Iraqi branch of al-Qaida had not just been revived but was also in a position to expand into Syria. Given that it had nearly a decade of military and governance experience, it was able to seize control of the largest swath of territory in eastern Syria. By 2013, it announced a merger with its then Syrian counterpart, Jabhat al-Nusra, and renamed itself the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). The central leadership of al-Qaida rejected the merger, but it was not in a position to reverse ground realities. ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi publicly chastised al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri and declared ISIS independent from al-Qaida.

A year later, ISIS seized Mosul, announced the re-establishment of the caliphate and declared itself “the” Islamic State. Clearly, IS emerged as the most powerful jihadist force in the Levantine-Mesopotamian landmass. However, that did not mean al-Qaida had been delivered a knockout punch. While it no longer had a presence in Iraq, it did have Jabhat al-Nusra to rely on after the group’s core was able to re-emerge following the falling apart of the 2013 merger. Since then al-Qaida has been working to distinguish itself from IS.

It is important to note that, fundamentally, al-Qaida and IS are very similar. They have sprung forth from the same basic Salafi-jihadist ideology, and they both seek to establish a caliphate. Ironically, al-Qaida has denounced IS as extremist and sees IS as a renegade movement that has hijacked the global jihadist movement. Al-Qaida believes that the ground realities needed for a sustainable caliphate will take decades to materialize.

IS, on the other hand, believes that al-Qaida has deviated from the cause because of an overcautious approach. IS also sees itself as having done the heavy lifting for the jihadist cause, which it feels led to the establishment of the caliphate. Put differently, IS feels it has succeeded in operationalizing what al-Qaida has largely theorized about. Unique geopolitical circumstances in the form of the collapse of the Saddam Hussein regime and the Arab Spring provided IS with the opportunity to establish its regime.

IS is also heavily sectarian in outlook. Its anti-Shiite stance is not so much purely ideological as it is geopolitical, given that it was founded in Iraq amid the disenfranchisement of the Sunnis. On the other hand, al-Qaida, which also despises the Shiites, does not see the Sunni-Shiite struggle as central to its goal. Furthermore, most of the noted ideologues of the jihadist world support al-Qaida and deem IS a rogue entity whose efforts to fast-track the caliphate are doomed to failure.

Thus, al-Qaida in Syria has been moving under the assumption that IS will crumble in the face of the onslaught from the U.S.-led international forces. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that it is actually hoping for it. That said, it is well aware that this will not happen soon. But that doesn’t matter for al-Qaida, given that it is on a much longer road to the caliphate.

Since its 2013 disassociation from then-ISIS, al-Qaida in Syria has been focused on trying to gain the leadership of the Syrian rebel landscape, which has been dominated by Salafi-jihadist entities of different stripes. For several years, it pursued this course as Jabhat al-Nusra, fighting alongside rebel groups in different parts of the country. Since IS had appropriated the transnational caliphate brand, Jabhat al-Nusra tried to assume the leadership of the Syrian nationalist camp. At the same time, however, it maintained its al-Qaida affiliation, which increasingly became a liability – preventing it from achieving its goal of becoming a leader of the rebels.

Finally, last summer it rebranded itself as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham and formally disassociated itself from al-Qaida. Since al-Qaida leader al-Zawahiri blessed the move, it is clear that the separation was not a genuine one. Six months later, the recapture of Aleppo by the regime proved to be another major opening for the group. The loss of Aleppo symbolized the massive collapse of the major rebel groups such as Ahrar al-Sham and many others.

The disarray in the rebel landscape created an opportunity for Jabhat Fatah al-Sham to join forces with a few smaller like-minded rebel groups to form Hayat Tahrir al-Sham two months ago. This latest al-Qaida incarnation in Syria also controls Idlib – the one province (situated between Latakia and Aleppo) that the regime has not regained control over in western Syria. From here, it is now preparing to fill the vacuum that will gradually emerge as IS weakens. The twin bombings are part of this effort and a way to show the rebels that despite the loss of Aleppo it has the wherewithal to take the fight to the regime’s doorstep.

This will obviously force the regime to respond and prioritize al-Qaida over IS. However, the regime’s forces are spread thin on multiple fronts. Meanwhile, IS is the priority of the U.S.-led international coalition. Al-Qaida’s strategy is to be ready to assume the jihadist leadership when the IS regime crumbles. This is one key potential way in which jihadism will persist long after IS has been degraded.