By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Sunday, Turkey will hold a referendum on constitutional changes that would increase the president’s power. The media’s narrative about this referendum is that a vote in favor of the changes would amount to the death of Turkish democracy. Some have even suggested that Turkish democracy is already dead and the referendum is the final nail in the coffin. Opponents of the changes believe a “yes” vote would elevate President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to the position of dictator in chief, and that Turkey’s turn to the dark side would be complete.

This line of thinking has one small problem. The decision to change the Turkish government’s structure will be based on a democratic vote. Dictators and authoritarians come in many shapes and sizes, and some have come to power by democratic means before crushing all opposition. But rarely are dictators concerned with the finer points of constitutional law and democratic legitimacy. If Turkish citizens vote in favor of the proposed changes, Turkey’s parliament will retain the right to impeach the president with a two-thirds majority. A “yes” vote on Sunday would not be a coronation; it would be a democratic expression of the will of the Turkish nation, or at least the portion that decides to vote.

“EVET” (Yes) campaign banners showing the portrait of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan are seen hanging on April 10, 2017 in Rize, Turkey. Chris McGrath/Getty Images

People may not like what Erdoğan has to say, but he is campaigning to the Turkish people, not forcing them into the voting booth at gunpoint. This is a real vote, and there is no better indicator of this than the fact that polls are split on which side will win. Reuters, for instance, reported last month that an ORC poll showed around 55 percent of Turkish voters would cast ballots in favor of the changes. Polling company Gezici told Reuters that none of its 16 polls saw a victory for the proposed amendment. The only thing that can be said with certainty is that the vote will be close. If this is not democracy, it is unclear what is.

Ultimately, this referendum is about politics, and superficial politics at that. Turkey is a society in transition and a country emerging as a regional power. Such processes do not unfold smoothly. Think of France on the eve of the French Revolution. Its economy was in shambles, and it had recently lost the Seven Years’ War (and most of its colonial possessions in North America). But French society was transforming from the inside while foreign challenges were pressing on it from the outside. The result was a bloody revolution that featured beautiful declarations on the rights of man alongside liberal use of the guillotine. Those who would criticize Turkey for abandoning liberal democracy by voting to give its president increased powers want liberal democracy only if it produces the outcome they prefer. They forget how liberal democracy came to the West in the first place.

Some will say this is a misreading of Turkey’s assault on the basic principles of liberal democracy. They will point to jailed journalists, fired academics and the Kurdish situation in the southeast as evidence of Turkey’s fall from grace. Some of these concerns are valid. However, it is also true that, a year ago, a significant faction in the Turkish military was planning a coup against Erdoğan and the democratically elected government. If the U.S. military attempted a coup against the U.S. president, a series of arrests and investigations undoubtedly would follow to protect the institutions of the state. Erdoğan may very well be using the attempted coup to consolidate his power bases and to rebuild Turkey’s institutions with people he can trust. But this does not make him evil, nor does it make Turkey a budding totalitarian regime.

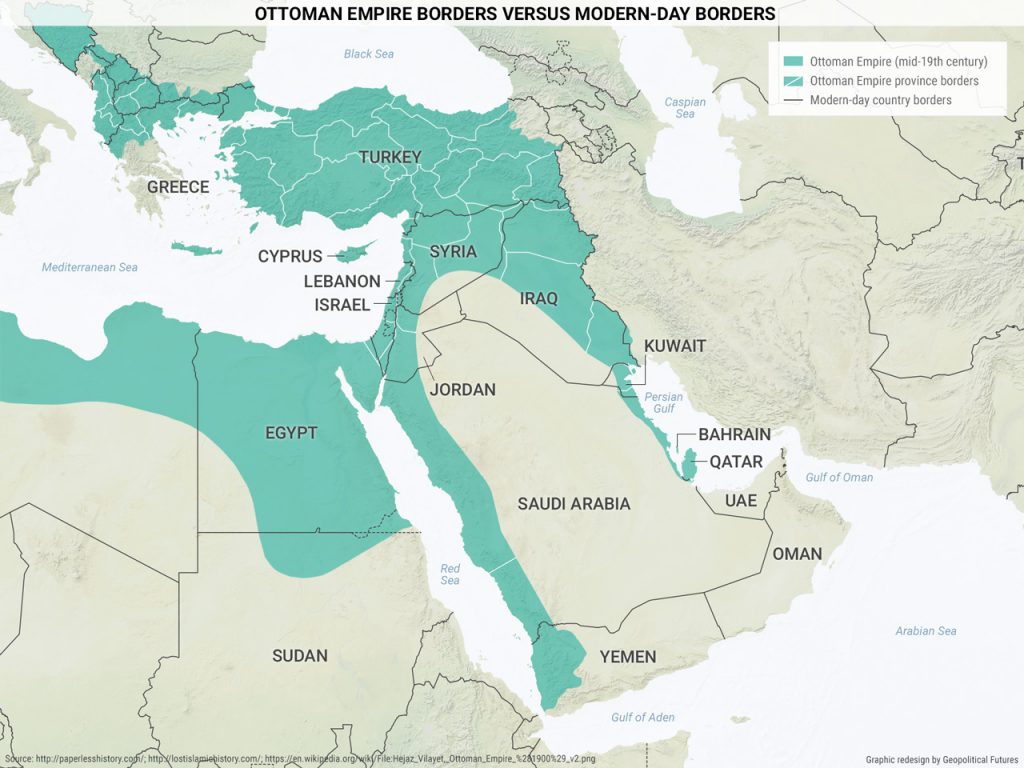

Of course, in a country like the United States, the military has never attempted a coup against the civilian government. The difference between a country like the U.S. and Turkey is their geopolitics. The modern Turkish republic was founded in 1923. It was both a weak power and an heir to a proud and illustrious imperial history that went up in flames after the Ottoman Empire collapsed following World War I and lost some of its former territories. Political power in the ghost of the country that emerged in 1923 was centered in Istanbul, even if the capital was Ankara, and Anatolia was weak, underdeveloped and underrepresented. Military officer Mustafa Kemal Atatürk became the country’s leader. For a long time, the military was the dominant force in Turkish politics, and it would intervene when it felt it was necessary.

The rise of Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party is part of the evolution of the weak, defeated country that was created in 1923. The current constitution, which sets out the framework for the Turkish government, was adopted in 1982 under a military regime that took power in the 1980s coup. During this decade, Anatolia, which had not been a major priority in either the Ottoman era or in the first decades of the Turkish republic’s existence, saw benefits from the Turkish government’s economic and political reforms. The influx of capital and industry into Anatolia created a new class of Turkish citizens, who had grown up more conservative and religious than the elites in Istanbul but preferred a more laissez-faire economic approach. The old power centers encountered the periphery in a way they never had before. This divergence between the two groups changed Turkish politics and continues to shape them today.

As this internal transformation has taken place, Turkey’s power as a nation has also increased. Turkey has the largest GDP in the Middle East. Only Saudi Arabia’s economy is comparable, and Saudi Arabia is in deep trouble. Geopolitical Futures has written extensively in the last year about the Saudi regime’s weakness: It is almost literally a castle made of sand built on a foundation of oil and little else. According to the World Bank’s latest figures, Turkey’s economy is almost double the size of Iran’s, yet Tehran continues to garner an inflated level of world attention relative to its power. From a military perspective, Turkey has one of the largest armies in the Middle East. Although the army was in need of reforms and modernization even before the attempted coup, Turkey’s ability to project military force is greater than most of its neighbors’. Its potential far outstrips the potential of other countries in the region.

For a while after 1991, Turkey was content to develop slowly and methodically. It pursued a policy of “zero problems” with its neighbors. But the Middle East has reverted to its normal state, somewhere between civil war and general chaos. The Syrian civil war and Iraq’s instability are not abstract issues for Turkey: They are happening on Turkey’s borders. Spillover violence is a fact of life for the country, as are the millions of refugees fleeing Iraq and Syria. Iran is attempting to assert its interests to the extent that it can, and Russia – one of Turkey’s historical enemies – is playing around in the region with limited force but in direct opposition to Turkey’s interests.

When Turks go to the polls on Sunday, they will be making a collective decision about the type of government they want. A “yes” vote may very well mean that Erdoğan will become a strong, authoritarian-style president until as far out as 2029. At that point, he would have to step aside due to term limits or his inability to continue governing, or change the constitution again. A “no” vote could mean Erdoğan’s power will wane, but it could also mean that he will remain powerful within the context of the current system or that some new force will rise in Turkish politics. Geopolitics is not sentimental about personalities. It dictates that Turkey will rise, not the name of the person who will lead it.

Regardless of whether Erdoğan stays in power or another leader takes over, Turkey will continue maturing as a nation and becoming a regional power surrounded on almost all sides by unenviable threats. If the referendum passes, Erdoğan’s authority will still be subject to checks and balances, but none will be as determinative as the geopolitical constraints forcing Turkey back into the pantheon of the world’s major powers. On that, Turkey doesn’t get a vote – and its increase in power will define the country’s future more than any referendum can.