By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Jan. 28, U.S. President Donald Trump spoke with Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull on the phone. The White House statement about the call was innocuous, describing a 25-minute conversation in which both leaders “emphasized the enduring strength and closeness of the US-Australia relationship.” Four days later, on Feb. 1, The Washington Post published a different account of the phone call. According to the Post, Trump was both dismissive and hostile toward Australia’s prime minister and ended the planned hour-long call after only 25 minutes. Who leaked what and why will be grist for the global rumor mill for a few news cycles. The important context to keep in mind is that the U.S.-Australia alliance is extremely important for both countries.

Those familiar with Geopolitical Futures’ writing already know that Australia needs the United States. Australia’s economy depends on global trade. Australia does not possess a global naval force capable of protecting maritime trade routes. This means Australia must have a tight relationship with a country that does. For much of Australian history, that was the United Kingdom. Since 1945, it has been the United States. China is by far Australia’s most important trading relationship – in 2015, 29.6 percent of Australian exports went to China, and 22.8 percent of Australian imports came from China. But a maritime trading relationship is meaningless if the goods cannot get from one country to another. This is the reason Australia needs the U.S.: The U.S. guarantees that maritime trade will move freely.

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks on the phone with Australia’s Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull from the Oval Office of the White House on Jan. 28, 2017, in Washington. MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images

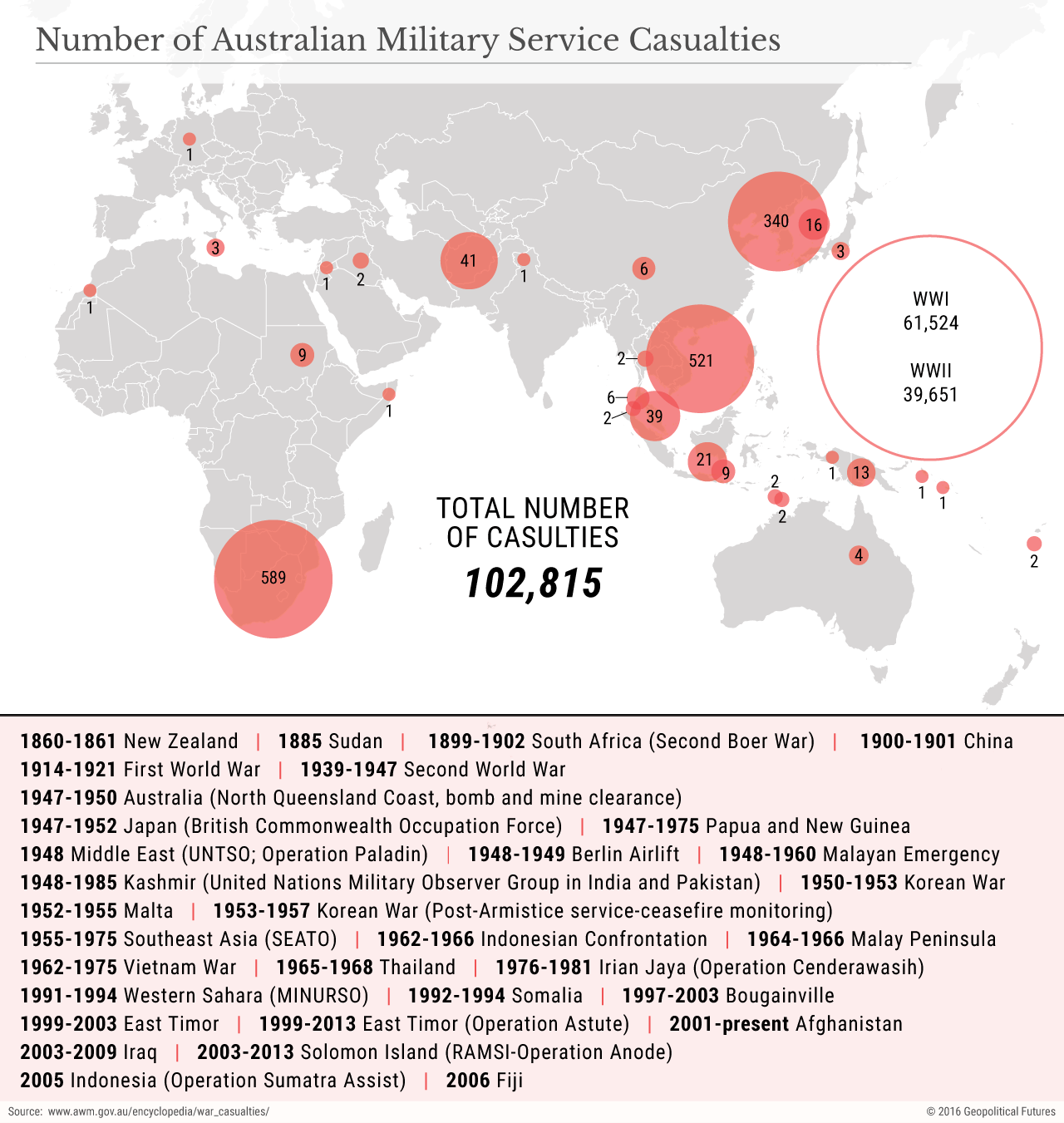

The less appreciated aspect of this alliance is that the United States also needs Australia. The U.S. is the stronger power of the two, but the relationship is not one-sided. It has been a foundation of U.S. strategy since World War II. The U.S. needed Australia when it fought the Japanese in the Pacific in World War II and during the Cold War to help contain the Soviet Union. The U.S. has called on Australia to commit troops to every war fought by the Americans since 1945, and Australia has answered the call each time, contributing much-needed credibility and support to U.S.-led military engagements. The U.S. and Australia are bound together formally by multiple treaties and share intelligence as part of the “Five Eyes,” the intelligence alliance between Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S. The U.S.-Australia alliance is one of the closest security relationships in the world.

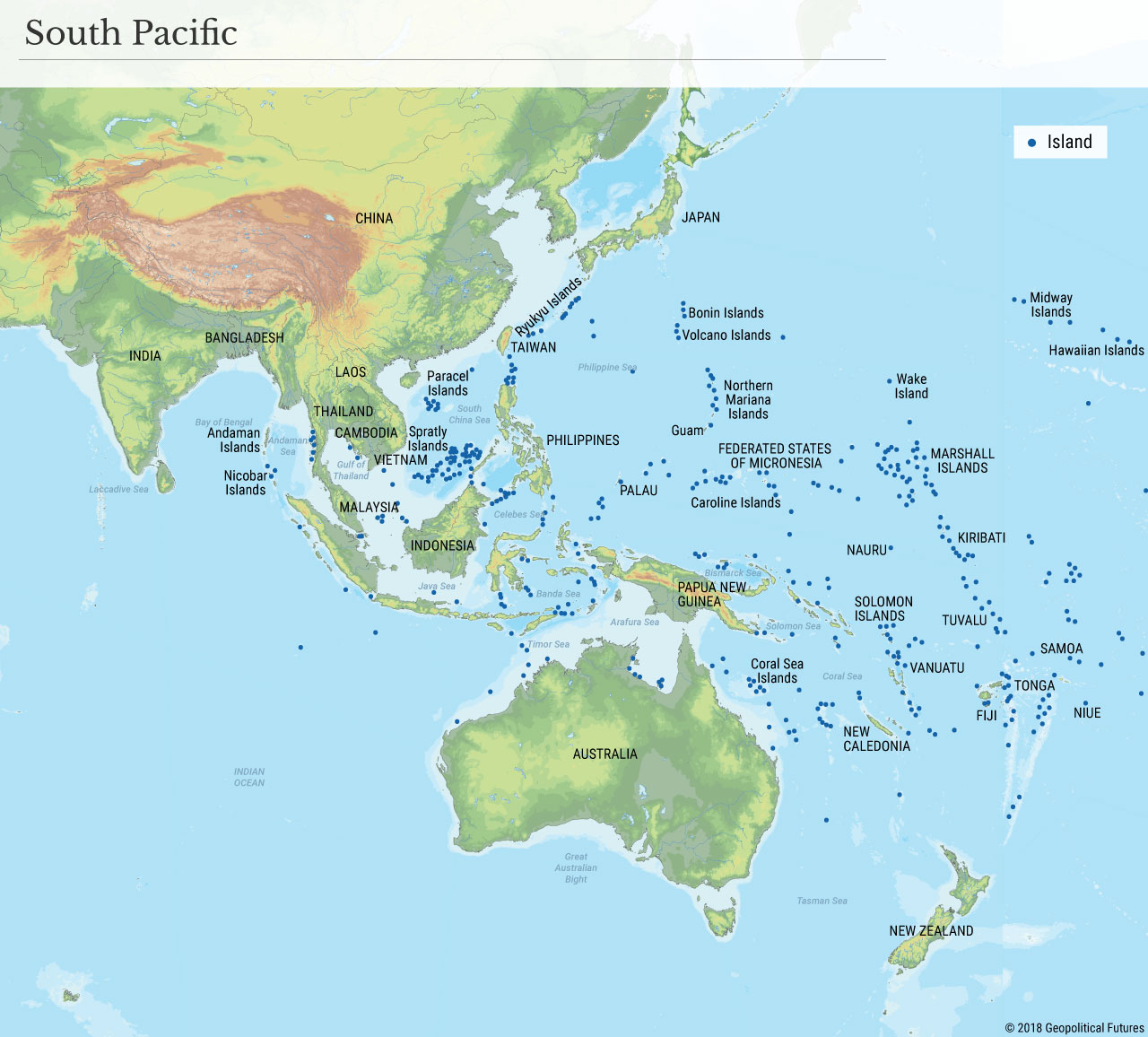

The U.S.’ reliance on Australia will become more acute in the coming years. For much of both countries’ histories, the Atlantic Ocean was the most important and strategic body of water in the world. This is no longer the case. Trans-Pacific trade has outpaced trans-Atlantic trade since the early 1980s. The second and third largest economies in the world – China and Japan, respectively – are in East Asia. The Strait of Malacca, located at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, is the world’s busiest trade route, with roughly two-thirds of the world’s oil and a third of the world’s bulk cargo transiting to and from the Indian and Pacific oceans. The U.S. holds no sovereign territory in this part of the world – Guam is the closest U.S. territory. U.S. power projection in the Pacific depends on good relationships with U.S. allies – Australia, Japan, South Korea and the Philippines the most important among them. Of these partners, Australia is the most reliable for the U.S. To maintain its superiority in the Pacific, the U.S. must have a close relationship with Australia.

This relationship is not just about maintaining a foothold in the region, however. It is about meeting new strategic threats by relying on U.S. allies to maintain a balance of power that benefits the U.S. in key parts of the world. The U.S. does not have the capability to intervene every time a potential problem arises. This means the U.S. must rely on alliances to prevent the problems from arising in the first place. The United States is the world’s strongest military and economic power, but this does not mean the United States is omnipotent. Under the Barack Obama administration, the United States began to shift the burden of defense and security to its security partners throughout the world. This shift was gradual and often polite, which masked the fact that it was happening. But the shift was no less tangible because it was courteous. The U.S. has signed new agreements on basing and deployment rights in Australia in recent years, but the U.S. has also pushed Australia to develop its own military capabilities and to assert itself in both its near abroad and the South China Sea.

Under the Trump administration, this process will accelerate. The new U.S. secretary of defense said in his confirmation hearing that the U.S.-led global order is facing its biggest challenge since World War II, and he identified threats from Russia and terrorist groups as well as Chinese aggressiveness in the South China Sea as the key challenges currently facing the United States. The most serious of those issues from Australia’s vantage point is China. The U.S. is prioritizing China as one of its main issues, both from an economic and security perspective. The U.S. will not withdraw from its security commitments to its allies, but it will insist that the burden of defense be shared more equally. The U.S. wants Australia to take a more active role in managing the South Pacific, but it also needs Australia to play a bigger role in the Pacific’s balance of power at large. The problem is that China, the country Australia is primarily balancing against, is Australia’s most important trading partner. This puts Australia in a difficult position, which is no different than the usual state of affairs. The U.S.-Australia relationship could be summed up as a series of instances where the U.S. has asked Australia to support U.S. moves in challenging situations.

As for why Trump would choose to embarrass such a close strategic ally publicly, the most we can offer is an educated guess. Trump campaigned on the immigration issue and has made it a defining part of his first 100 days in office. The fact that the U.S. had a prior agreement to take 1,250 refugees, most from countries Trump banned from entering the U.S. in last week’s executive order, from two Australian offshore detention centers might anger his base, whose support he must maintain. Perhaps someone intentionally leaked parts of the conversation between Trump and Turnbull to The Washington Post so that Trump could score domestic political points at Turnbull’s expense, while still behind the scenes begrudgingly living up to a prior U.S. commitment to a key ally. The fact that Trump tweeted about the immigration issue a few hours after the Post article appeared increases the likelihood of the possibility, but there is no way to confirm where the leak came from and the intention of the person responsible.

What can be said is that the U.S.-Australia alliance goes beyond personalities. Personality clashes between U.S. and Australian leaders have happened before, but the two countries’ imperatives have kept them close and will continue to do so. Australia does not have a viable option to replace the U.S. security guarantee, and the U.S. must maintain a close relationship with Australia to secure its position in the Pacific and keep the containment line against China’s ambitions in the region robust. Need is a more stable basis for an alliance than affection.