By Cheyenne Ligon

The Iraqi offensive on Mosul has ground to a halt. At the end of last week, reports indicated IS had taken back multiple neighborhoods in eastern Mosul from Iraqi Security Forces (ISF). Then, on Dec. 19, the Institute for the Study of War reported that U.S. military officials said the elite Golden Division, the U.S.-trained and equipped Iraqi force leading the assault on Mosul, had a casualty rate of 50 percent, which would render it combat-ineffective within a month. This is a significant indicator that the fight against IS in Mosul is not going well. In an in-depth study, we explained why eliminating IS in Mosul was going to be so difficult. That difficulty is becoming increasingly apparent, and the latest reports of IS effectiveness against Iraq’s best-trained forces aligns with our forecast that the battle for Mosul is going to extend long into 2017.

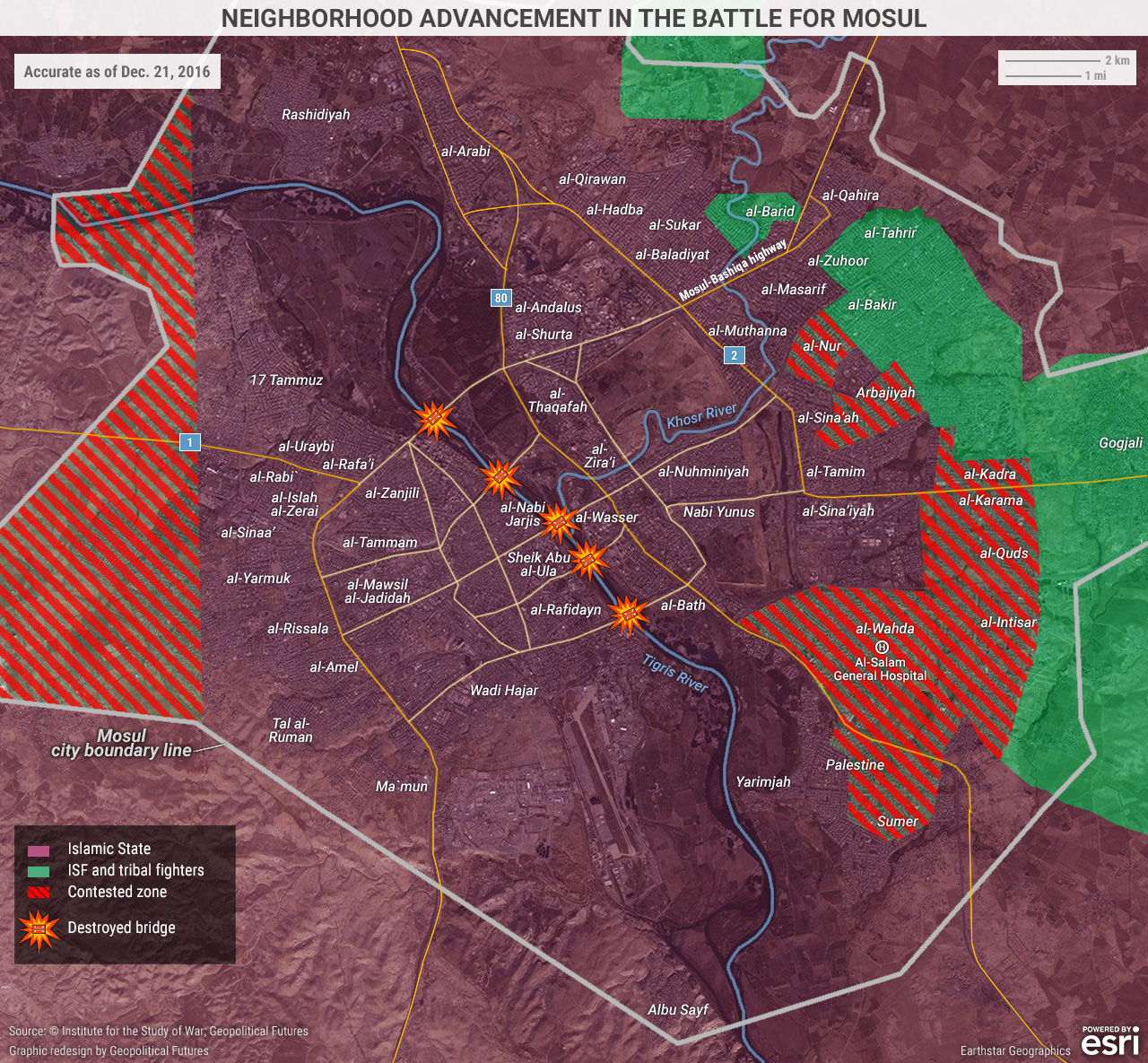

Iraqi forces have reclaimed approximately a quarter of Mosul since the battle started on Oct. 17, with most gains made on the eastern side of the city. Last week, they reached the Khosr River, a tributary of the central Tigris River, which separates eastern and central Mosul. ISF’s strategy – to encircle the city and push IS inward from the north and the east – means that the fight will become increasingly difficult as Iraqi forces enter the central part of the city. Reports suggest that IS has barricaded itself in government buildings and the University of Mosul, which lie just beyond the Khosr River. Once they have forded the Khosr, the Iraqi forces will face larger numbers of IS fighters, likely more densely packed and deeply entrenched than they are in the city’s eastern edges. No tangible progress has been made since the Iraqi forces reached the Khosr last week. A deputy commander for the coalition’s air force told media that the Iraqi forces were stopping to take time for a planned, operational refit after 65 days of continuous fighting. Though the forces need time to regroup and plan the difficult next stage of their assault, the high casualty rate is certainly the most significant factor that led to this pause.

The vanguard of the Mosul offensive has been three brigades of Iraq’s Counter Terrorism Service (CTS), numbering approximately 10,000 men. The CTS has done much of the heavy lifting in Mosul, retaking neighborhoods from IS and pushing forward, leaving behind regular members of ISF or Iraqi Federal Police to hold the territory. Because the forces left behind to guard the newly retaken territories are often less trained and equipped, they are vulnerable to IS fighters who double back once CTS troops have moved to other areas of the city. Last week, IS retook three eastern neighborhoods from coalition forces. Efforts by non-CTS forces to seize territory from IS have not gone smoothly. The al-Salam hospital in the southeastern al-Wahda neighborhood has been a site of active fighting between coalition forces and IS for nearly two weeks.

Iraqi Special Forces gather next to their armored vehicles in the neighborhood of al-Barid, east of Mosul, on Dec. 18, 2016 during their ongoing operation against the Islamic State to wrest back the city. MAHMOUD AL-SAMARRAI/AFP/Getty Images

The large disparities in training, equipment and morale within the ISF are part of the reason IS will be so difficult to dislodge from Mosul. The CTS is not large enough to both push forward and hold territory. Iraqi forces may be forced to increase their reliance on militias to hold areas they have taken, which will damage their cohesion. In contrast, IS has a unified fighting force in Mosul with a relatively equitable distribution of training and equipment. It is willing to stand and fight. It has had two years to settle into Mosul, allowing it to set booby traps and become familiar with the city’s layout. Urban warfare is brutal, and IS’ entrenchment in Mosul gives it a significant advantage against advancing Iraqi troops.

The battle for Mosul is a test of endurance. Though the coalition has more fighters and better equipment compared to IS’ estimated several thousand fighters and limited supply of weapons and ammunition, IS has home field advantage and nowhere to retreat. IS’ strategy is to make the cost of taking Mosul so high that it will discourage the ISF from continuing to wage what is already becoming a war of attrition. IS is besieged, outnumbered and outgunned, but it has the advantage that Iraqi fighters want the battle to end quickly, while preventing as many civilian and military casualties as possible.

Even if IS is eventually defeated in Mosul, this battle demonstrates the strength of IS. It has proved very difficult to dislodge from Mosul, successfully resisting a fighting force over 10 times its size. This is even more significant when we consider that, though important to IS, Mosul is not part of its core territory. While the battle for Mosul rages, IS is fortifying its positions in Raqqa and Deir el-Zour. It has pulled fighters from Mosul and repositioned them in Syria, it accumulated new weapons and vehicles through its attack on Palmyra, and it is preparing for the fight that really matters. IS seized the entire city of Mosul in less than a week. The coalition is predicting it will take six months to a year to take it back. And with a casualty rate of 50 percent for its main attack force in Mosul, the human cost of retaking the city is coming into relief.