By Lili Bayer and Jacob L. Shapiro

In May, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer presented a report to Parliament outlining the short-term impacts of a vote to leave the European Union. According to the report, a vote to leave would cause “an immediate and profound economic shock,” pushing the U.K. into a recession and leading to a sharp rise in unemployment. The British Treasury was not alone in its fears: investment banks and consulting firms across the globe issued predictions of imminent doom. The Financial Times even reported that international banks were beginning to look at real estate in Frankfurt because London was no longer a suitable place to do business.

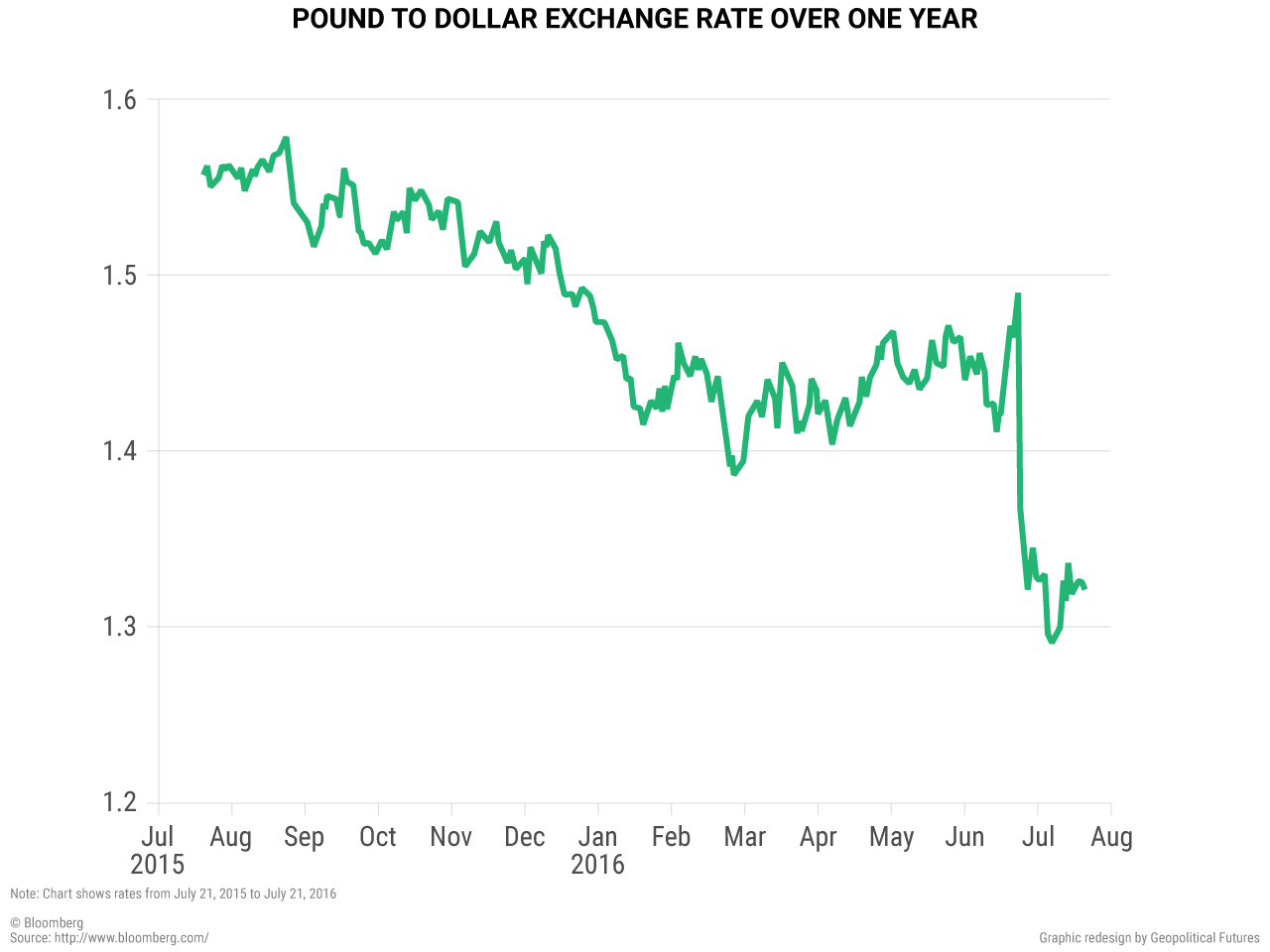

There was a general atmosphere of panic and hysteria leading up to the vote that exploded once it became clear that the “leave” campaign won. Global markets reeled and the British pound plunged to a 31-year low. The European Central Bank (ECB) issued a statement saying it “stands ready to provide additional liquidity, if needed, in euro and foreign currencies” and has “prepared for this contingency.” The Bank of England announced it would make £250 billion ($331 billion) of additional funds available to help stabilize markets. Headlines and stories abound at the immediate and profound impact Brexit would have on the British economy.

And then the doom didn’t materialize.

The atmosphere leading up to and just after the Brexit vote is markedly different than the relative calm that is pervading now. The first signals of cautious positivity came on July 14, when the Bank of England — despite referring to a “significantly lower path for growth” — opted to hold its benchmark rates and wait to see the impact of Brexit. A week later, the bank issued a report noting that there was no clear evidence of a sharp slowdown in business activity in the U.K.

Last Friday, the chief economist for the Bank of England said that the bank needed to come up with a strong monetary response to stimulate the British economy promptly – but then said that, by promptly, he meant “next month.” A crisis that can wait a month isn’t exactly doomsday. Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, said yesterday in a statement that the eurozone had “weathered the spike in uncertainty and volatility with encouraging resilience.” Brexit has gone from being a cataclysmic event to something that can be managed in a meeting in a month’s time.

There were three basic misunderstandings about Brexit that became commonplace.

First and most important, some people believed they knew what the effects of a “leave” or “remain” vote would be. Instead of simply stating the uncertainty, reports were issued claiming to knew the consequences of the vote to back up political positions against (or for) leaving the EU. These reports overstated British involvement in the EU. They defined membership in the EU as more important than the fact that the U.K. is part of Europe whether it wants to be or not. The highly interconnected economic relationships it has and will continue to have with EU members were not going to evaporate overnight. People underestimated Britain’s close relationship with the United States and generally dismissed all outcomes as uncertainty rather than identifying potential opportunities.

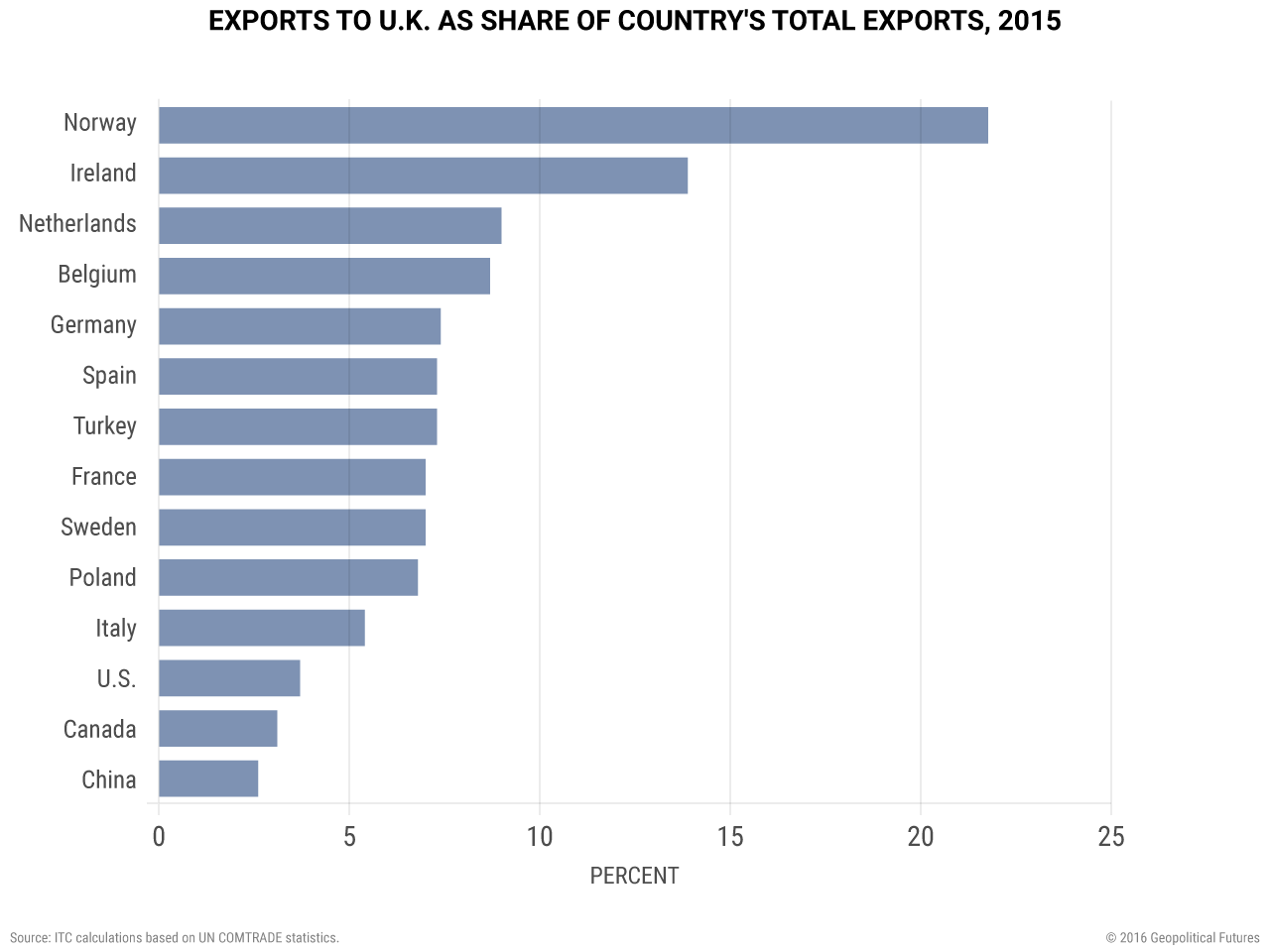

Most crucially, those who were certain a vote to leave would have disastrous effects failed to grasp just how important economically the U.K. is for Europe. Over 45 percent of Germany’s GDP is from exports; it isn’t about to drag one of the most important markets for its exports through the mud. Indeed, the willingness of leaders like German Chancellor Angela Merkel to consent to a longer than planned negotiating timeline indicates that both sides want a comprehensive deal that would allow much of the current economic activity between the U.K. and the bloc to continue unobstructed.

The second misunderstanding was also one of the reasons British voters opted for Brexit in the first place. Those who wanted to remain in the EU presented the issue as strictly economic. They felt that if they could demonstrate that, economically, remaining in the EU was far better than leaving, the voters would fall in line. But for many who voted to leave the EU, the issues that concerned them were not economic. Their concerns were first and foremost related to sovereignty, politics and immigration. Although the British government produced a 90-page study with complex modeling about why leaving would be bad in the long run for the British economy, those who voted to leave were more concerned about Germany lecturing Britain on its immigration policy. They were willing to endure some hardship to ensure that didn’t continue to happen.

The third misunderstanding was not correctly grasping that the length and complexity of the negotiating process meant that Britain’s exit was not going to happen overnight. The British government has not yet triggered Article 50 (which formally starts the withdrawal process) and even once Article 50 is triggered, the U.K. will have two years to negotiate the terms of its leaving. On July 20, Merkel supported the decision of new British Prime Minister Theresa May to wait until 2017 to trigger Article 50 – so the absolute earliest the U.K. could leave the EU is 2019. This means that the British government – as well as domestic and foreign businesses – have plenty of time to adjust to new regulations and policies before the U.K. formally leaves the bloc. This extended transition period means a rapid change in business conditions in unlikely.

This is not to say that the result of Brexit has been all rose petals and biscuits. The British pound has lost roughly 10 percent of its value. British companies will be hurt by this and there is the potential for decreased growth, increased unemployment and inflation. Although, on the other hand, a weaker pound could boost British exports.

The point here is not that we think there will be no negative consequences as a result of Brexit. There will be some and some might be quite painful. But we said before the referendum that if Britain voted to leave, these challenges would not be insurmountable and the histrionics surrounding a potential decision to leave were overblown. That remains our overall position and if you want to see how we arrived at that conclusion, our Deep Dive goes into the nitty-gritty details of our reasoning.

As to whether Britain will fall into recession, the answer to that is of course it will at some point. All healthy economies do. Whether Brexit will be the precise cause of that recession is another story. One of the reasons the “leave” supporters felt comfortable with their position was that when they looked across the English Channel, they didn’t like what they saw. Europe’s economy is generally stagnant and the EU is an overly bureaucratic institution that still has not recovered from the 2008 financial crisis and has proven incapable of responding to other crises, whether they be tied to migration issues or Italian non-performing loans. The U.K. may be on the edge of a recession – we expect the U.S. is closing in on a cyclical one itself – but the U.K. would be on the edge of a recession either way because it is also on the edge of Europe.

There is an extremely valuable lesson in this for those who care deeply about geopolitics. The lesson is that one should not pay much attention to inevitable short-term responses to unexpected events. And the reality check is that the reports of Britain’s demise post-Brexit were greatly exaggerated.