By Jacob L. Shapiro

Charisma is one of those words that has been used so often and in so many contexts that its meaning has been forgotten. It is usually used today as a catch-all term for an individual’s likeability. For example, when John Kerry was running for president in 2004, The Nation analyzed his choice of John Edwards as vice-presidential candidate as stemming from a desperate need for a “charisma infusion,” which Edwards offered in the form of his skill in managing the press, and the effortlessness with which he could campaign to voters one-on-one. Trying to understand Brexit or Donald Trump’s election without a proper understanding of this word is like trying to win a soccer game by starting with two fewer players on the field than the other side.

Possessing charisma does not mean simply that one has a forceful or compelling personality. The word came into English from Greek by way of ecclesiastical Latin in the mid-17th century, and the original root “kharis” means “grace.” If you were literally to translate the word into English, the definition would be “gift of grace.” The word has an overtly celestial character. It denotes a talent or quality that seems divinely bestowed. More than that, the word implies not just that an individual possesses a unique gift, but also that other people have faith in the individual as a result. It is impossible to speak of charisma without the irrational devotion by a group of followers that accompanies it.

Donald Trump addresses supporters during a campaign rally on Nov. 8, 2016 in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Scott Olson/Getty Images

The man who made charisma an important word for the study of geopolitics was Max Weber. In his lecture-turned-essay “Politics as a Vocation,” Weber introduced the idea that a state or political institution can justify its authority over citizens or subjects in three different ways. The first is by way of tradition, and the third is by way of legality – we might even say bureaucracy. The second justification Weber identifies is charisma, which he describes as “the authority of the extraordinary and personal gift of grace (charisma), the absolutely personal devotion and personal confidence in revelation, heroism, or other qualities of individual leadership. This is ‘charismatic’ domination, as exercised by the prophet or – in the field of politics – by the elected war lord, the plebiscitarian ruler, the great demagogue, or the political party leader.”

Two things must be stressed in this definition. The first is that charisma has an irrational quality. At its core it is a leap of faith. It can be rationalized, and political coalitions can be formed between the true believers and those who have other reasons for joining the cause, but the core of charisma is the complete surrender to a belief in a particular person’s unique qualities.

The second part that must be stressed is that charisma is not something that one can simply possess. As Weber wrote, the most important part of charisma is not how an individual carries himself or herself, but rather how followers or disciples regard that individual. Charisma is both irrational and defined not by the individual who possesses it, but rather by the people who ascribe it to an individual.

Trump was a charismatic candidate for the presidency, and he will be a charismatic president. For those who dislike his affectations or personal style, that sentence will produce a certain degree of cognitive dissonance, but affect and style have relatively little to do with the phenomenon of charisma as defined above. Charisma is exhibited in a liberal democracy in the way that it causes people to vote because of faith in a particular candidate rather than out of self-interest.

This is one of the many reasons all of the polls got this election wrong. Polls are built on rational models and past performance. Trump was running against the first female candidate for the presidency, and despite the revelation of his casual attitude towards sexual assault, he won almost the same percentage of the female vote as Mitt Romney in 2012. According to The Washington Post, 45 percent of white women with a college degree voted for Trump. No polling model could have predicted or can explain that. Initial exit polls show similarly surprising results among black and Hispanic voters, where Trump did better than Romney, when by every indication Trump should not have done well.

To be clear: This is not the only reason people voted for Trump; it’s not even the primary reason he won. We’ve written about Hillary Clinton’s blunders, the Democratic Party’s abandonment of the white middle class, and the very real grievances and issues that drove many voters into Trump’s camp. But this was an incredibly close election. To explain why Trump did much better than expected among these minority voting groups and so strongly in his core constituency, and how every Trump scandal that appeared – no matter how controversial or lewd – didn’t seem to stick, you must go beyond simple dissatisfaction. The dissatisfaction was there, but so was an irrational faith that Trump was going to “Make America Great Again.” Without charisma, he wouldn’t have won 270 electoral votes.

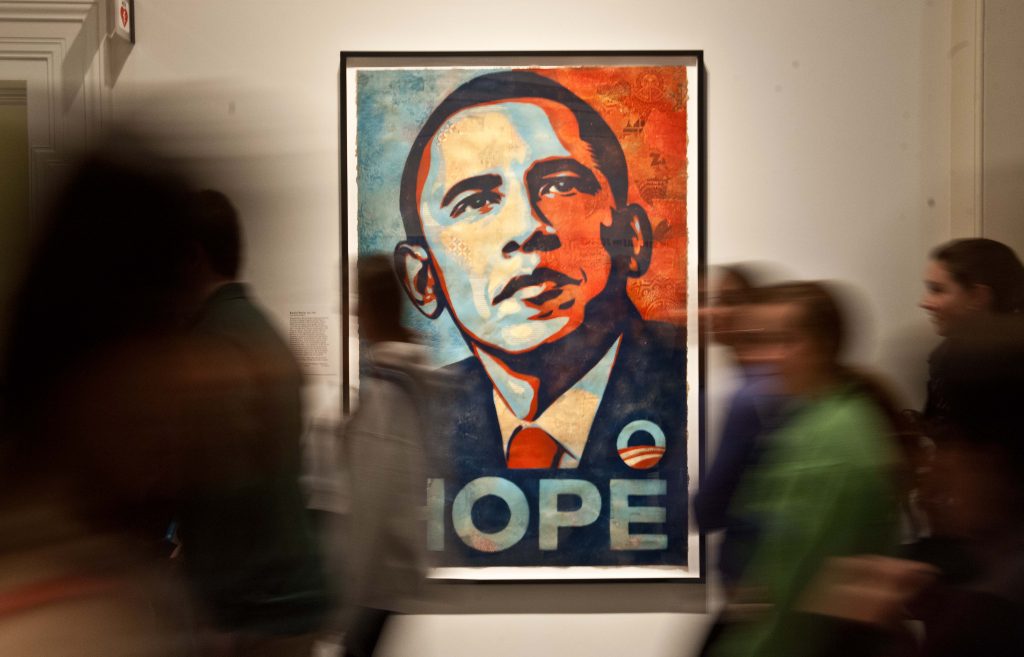

Shepard Fairey’s portrait of U.S. President Barack Obama, based on a photograph by Mannie García, at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 19, 2013. NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images

Charisma as defined above played a significant role in two other recent instances. The first was current U.S. President Barack Obama. The same irrational quality that is evident in some support for Trump was also there in the support of Obama. If you looked at Obama’s record and his position on issues, it was clear from the beginning that he was a pragmatist and moderate compared to those who were wildly enthusiastic about his candidacy. The facts didn’t matter so much as they believed “Yes We Can,” and that Obama was going to fix all of America’s issues, from its wars in the Middle East to the health care system. Obama had charisma. Europeans believed it, too, giving Obama a Nobel Peace Prize before he’d accomplished anything. Needless to say, Obama did not turn out to be the president these people thought he would be, and the disillusion with this wing of the Democratic elite played a role in Clinton’s underperformance in the demographics she expected to dominate. This wasn’t decisive, but it was part of Obama’s appeal to a substantial bloc of his supporters.

Brexit is another recent example of how polls failed to diagnose correctly how a vote would turn out. Nigel Farage, leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), is a charismatic leader. Sooner or later the issue of British sovereignty was going to be raised – the structural problems inherent within the European Union guaranteed that. That it was raised now, in the way it was, has a lot to do with Farage himself. UKIP only won 12.6 percent of the vote in the latest British election, and just one seat in the House of Commons (Farage lost the election). But that 12.6 percent loves Farage, and as he showed on the night of the referendum, Farage can bring supporters in droves to the polls. The majority of those who voted for Brexit are not prospective UKIP voters or Farage devotees. But charisma can apply to small factions as well as larger majorities. Farage tapped into a highly motivated group of voters who wanted to block immigration and take back sovereignty, and who are skeptical of British cosmopolitanism. Without the enthusiasm of these voters, Brexit may have happened in a different manner or on a different timeline.

Those who read us often know that from our perspective, nations are far more important than their leaders, and objective geopolitical forces shape events far more than individuals. None of what is written above contradicts that. Unlike tradition or law, charisma is powerful, but usually transitory, because people stop believing if what they want is not delivered. Between the Founding Fathers’ checks and balances and the constraints that define U.S. foreign policy no matter who the president is, Trump is going to have a very difficult time making good on all his promises. But two things must be kept in mind. First, a concomitant part of global dissatisfaction with political elites is the scapegoating of those who represent the status quo and an open-mindedness to those who promise quick fixes. As dissatisfaction rises, so will charisma. Second, charisma is by its nature unpredictable. It is a byproduct of geopolitical forces and is ultimately governed by those forces. But it also can cause those predictable forces to manifest in quite unexpected ways in the short term.

Weber presented his ideas of charisma in Munich in 1919, after World War I. He delivered his thoughts in the midst of the German Revolution and in part was trying to explain to students how and why these things happened to Germany. World War I and its consequences were far more important than Brexit or Trump’s election, but it also happens to be another example of an event that was not expected by most of the experts and the pundits. For those seeking to understand how the seemingly irrational fits into the orderly development of geopolitics, returning to Weber’s definition of charisma is as a good a place as any to start.