By George Friedman

U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has appointed retired Lt. Gen. Michael T. Flynn as his national security adviser. Flynn likely will play a pivotal role in U.S. foreign policy. The center of gravity of his career was fighting in the Middle East, with multiple posts as an intelligence officer in Iraq and Afghanistan and as head of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), from which he was effectively fired by President Barack Obama for objecting to how the wars in the Middle East were being fought and how intelligence was carried out.

It is difficult to know what his views are on most of the world. He visited Russia at Moscow’s expense and met with Russian President Vladimir Putin. I also visited Russia at their expense – I didn’t meet Putin, but rather lesser figures appropriate to my lack of status. You can meet someone, like someone and not be seduced by them. This is less a defense of Flynn than a defense of all of us who travel to faraway places, drink heavily and manage to stay sober.

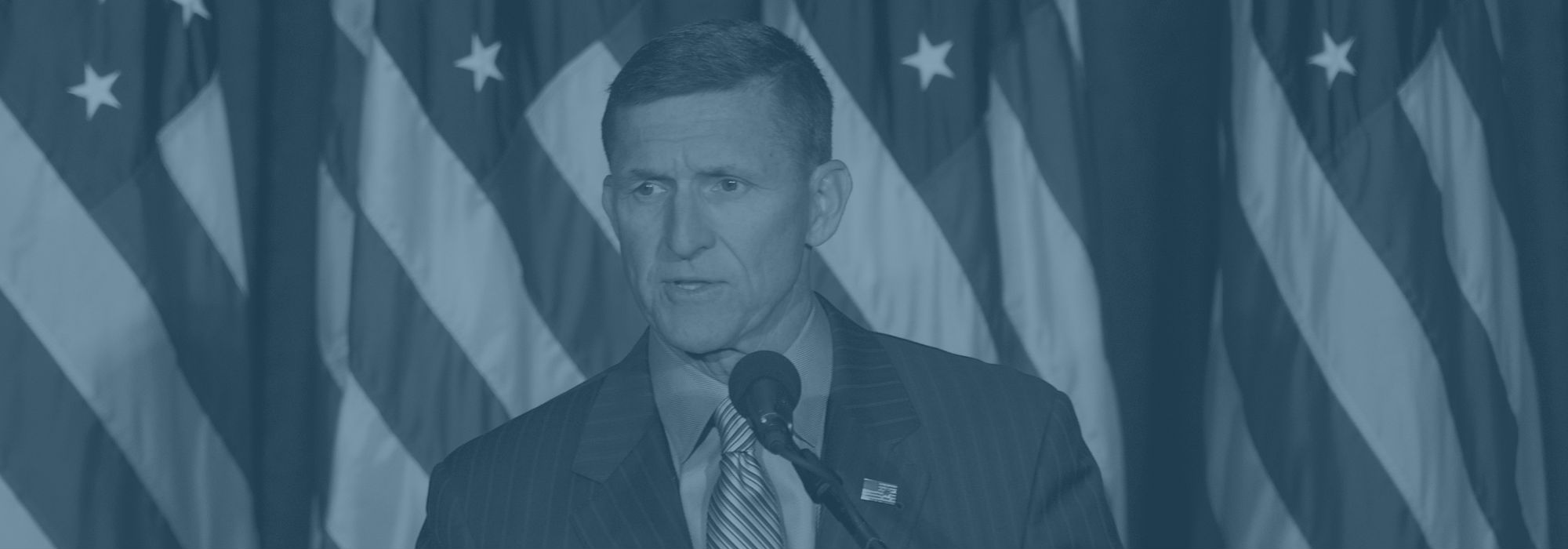

Retired Lt. Gen. Michael T. Flynn introduces then Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump at The Union League of Philadelphia on Sept. 7, 2016. Mark Makela/Getty Images

That said, Flynn is not a complete mystery. His views of the wars in the Middle East are clear, idiosyncratic and likely provide a sense of his views on other things.

While running intelligence in Afghanistan, Flynn objected to the way the war was being fought. He believed the enemy was not understood, and that military intelligence focused on the purely tactical failed to provide the material from which a strategy could be formed. The essential criticism he made was that the nature of the enemy was being neglected. He also believed that rather than steeping themselves in history, the intelligence community was focused on mounting operations against various objectives, failing to realize that victories in all of those operations did not add up to winning the war.

From Flynn’s perspective, wars in the region were deeply embedded in history, and particularly in the history of Islam. The forces the United States was fighting didn’t suddenly spring to life a few years ago. They were part of the deep structure of Islamic doctrine, and such conflicts were a recurring theme in Islamic history. Without understanding this, the U.S. could not succeed – and hadn’t succeeded.

He blamed two forces for this. One was the unwillingness of the Obama administration to recognize what the Taliban or Islamic State willingly acknowledged: their rootedness in Islam. But he also blamed U.S. intelligence. U.S. intelligence, both military and civilian, had focused warfighting on destroying al-Qaida, IS and the Taliban. U.S. intelligence methodology consisted of identifying senior leadership, using intelligence gathering to locate that leadership, and then killing them with airstrikes, drones or special operations units. The assumption was that eliminating the fighting entity would end the war, and eliminating the command structure would eliminate the fighting entity. Flynn objected to this by pointing out that over a decade, the enemy hadn’t collapsed, and in the long term, at the very least, maintained its strength.

Flynn argued that this was an unsophisticated strategy that suffered from any serious understanding of what motivated the groups. First, groups like al-Qaida and IS that arose historically drew their strength from moral values and communities that shared those values. If you destroy one organization, another will arise. If you destroy the leadership, other leaders will emerge.

Flynn’s point was that there was a dual problem. The first was that Obama’s refusal, whatever its origin, to recognize that the groups the U.S. was fighting did not spring out of nothingness or out of some marginal source vaguely connected to Islam. This was not a marginal group of malcontents but an integral part of Islam. He also felt that denying that was costing the U.S. casualties without hope of a victory. But he also slammed the intelligence community for putting aside scholarship or analysis that came from the outside. Flynn has a different view of intelligence: Its purpose is to provide the decision-maker with comprehensive knowledge of reality. The doctrine that “if we didn’t steal it, it isn’t intelligence” provided a limited and sterile background that didn’t challenge the assumptions on which the war was based.

Flynn’s argument was not that all Muslims are terrorists, by any means. Rather, without understanding the Islamic roots of these groups you cannot understand why our strategies in the Middle East were failing. The simplistic expectations that eliminating leaders of groups the U.S. was fighting would lead to victory vastly underestimated their core strength as individual soldiers, and the support of communities that would sustain them. The U.S. was merely cutting fast-growing branches – the smaller ones – of a robust tree. If the U.S. did not get to the roots, the war could not be won.

What is most interesting is Flynn’s attack on the intelligence communities for their inability to grasp that the most important things about the war weren’t to be gathered by advanced electronics, but rather by reading books. The open source, by which he meant anything not produced by someone pulling a paycheck from an intelligence organization, contains truths that must be learned if the secret intercepts are to make any sense. I suspect he must have read deeply in order to come to this conclusion. Since I confess to having built Geopolitical Futures on this principle, I admire him for it.

I imagine that if he recruits Trump for this mission, or if Trump will give him free rein, Flynn can compel U.S. intelligence to see the world more clearly. I strongly suggest he will have a very different war in mind, or argue for ending the war. What he will argue for the rest of the world is less clear. As a soldier he understands the importance of not undertaking missions built to fail, making certain he can survive both victory and defeat, and that war is not an abstract concept. Even more importantly, he will grasp the necessity of looking at the world through the enemies’ eyes – not out of sentimentality, but to recognize their weaknesses.

Flynn’s great weakness is that he battled his commanders in Afghanistan and the DIA’s president. From this I gather that the subtlety of the Borgias, which is what you need in Washington, wasn’t given to him as a gift. But he has Trump, a total wild card, backing him for now, so all things are possible. In any case, we have our first glimpse at how the world will look for Trump, since it will be Flynn painting the picture.