By George Friedman

President Donald Trump’s national security adviser resigned late Monday night. Michael Flynn admitted in his resignation letter to having conversations with the Russian ambassador to the United States and providing then Vice President-elect Mike Pence with an incomplete account of those calls. There is speculation that Flynn spoke to the Russian ambassador to the United States concerning U.S. sanctions against Russia before Trump’s inauguration. The Washington Post reported that the acting attorney general told Trump last month about the calls and suggested that Flynn was vulnerable to Russian blackmail.

I am missing something here. This isn’t meant to defend Flynn. It just means that I am missing something. There are two things that do not make sense. The first is that Flynn was an intelligence officer in Afghanistan and Iraq and at one point was the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency. Flynn knows intelligence. It is a stretch to believe that Flynn could have placed himself in a position to be blackmailed by the Russians. This is because there is no way Flynn didn’t himself know that phone calls he had with representatives of Russia or another foreign government were monitored. There is something mysterious in this; we still do not have clarity over precisely what happened.

The second reason this doesn’t make sense is that talking to the Russian ambassador by itself would not have been grounds for dismissal or resignation. Under the Logan Act, which dates to 1799, it is illegal for someone not in the U.S. government to conduct foreign policy negotiations with a foreign power on behalf of the United States. However, no one has ever been prosecuted under the Logan Act. Logan Act or not, private citizens are constantly engaged in conversations with foreign officials. Frequently, the conversation has some substance that might be transmitted back to a government official he might know. He might wind up as a go-between – not authorized to negotiate, but nevertheless negotiating. The issue here is not necessarily that Flynn had contact with the Russian ambassador. It is that Flynn did not accurately portray the contents of their conversation.

Consider this. Anyone named to the post of national security adviser knows numerous officials from foreign governments. It is a job requirement. Before an election, he is simply a private citizen, as free as anyone else to speak to foreign officials within the limits of the Logan Act, which is never enforced but widely violated.

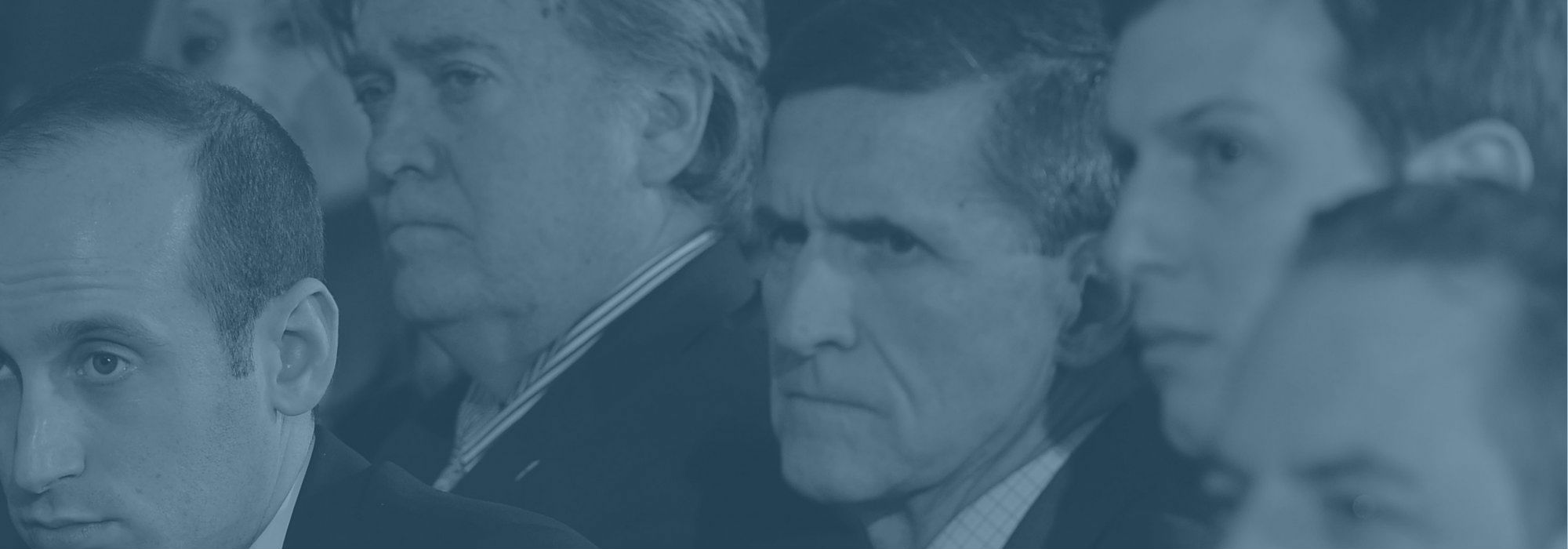

Third from left, National Security Adviser Michael Flynn attends a joint press conference of U.S. President Donald Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Feb. 13, 2017 in Washington, D.C. Pictured with him are, from left, Trump senior adviser Stephen Miller, White House Chief Strategist Stephen Bannon, senior adviser Jared Kushner and White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, on Feb. 13, 2017 in Washington, D.C. MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images

After an election, the president-elect is not yet the president and cannot speak for the U.S. government, nor can anyone he may have announced who will be a government official. But there is a difference between negotiating on behalf of the government and opening channels with foreign countries in anticipation of becoming part of the government. The idea that there should be no contacts whatsoever would mean that the new president would be starting from square one rather than hitting the ground running.

There is a famous but not fully confirmed example. In 1980, during the Iran hostage crisis, representatives of Ronald Reagan made contact with the Iranian government to discuss the timing of the hostages’ release. Contacts supposedly were made before and after that year’s election. What transpired in those discussions is disputed, but it is almost certain that conversations happened. Apart from this, it would be shocking for an incoming team not to have informal discussions with allies and major adversaries. It would be understood, of course, that the interlocutors did not speak for the U.S. government and could make no commitments.

Therefore, I would expect the national security adviser to have introductory conversations from the moment his appointment was announced and give some indication of the direction in which the new administration might go. Allies like the United Kingdom and Canada would expect a sense of the president-elect’s thinking.

Flynn’s case is obviously different, particularly because Trump withdrew his support from Flynn. That is not the president’s style. The reason for this is the part I am missing and the thing that makes it more than a minor Washington scandal. Whatever Flynn did, it appears that his actions went well beyond the norms.

Flynn had phone conversations with the Russian ambassador. It is likely that sanctions were discussed: In any discussion with a U.S. national security adviser, this topic would be raised by the Russian ambassador. The two supposedly had several phone conversations on the same day, which makes it somewhat more uncomfortable, simply because the reason to have more than one discussion was for both sides to consult their superiors. And that goes beyond merely opening doors to something substantive. But it’s still not enough for this type of crisis. As with Reagan’s people, substance is sometimes discussed.

In trying to understand what might have happened, we should consider Flynn’s main focus. Flynn had been head of military intelligence in Afghanistan. At the Defense Intelligence Agency and in a book he published, these were primary concerns. The president indicated that a key foreign policy goal was to crush Islamic State. It was also clear that this could only be achieved through a coalition, and Flynn indicated that Russian participation in the war on IS would be beneficial. The Russians have their own problems with jihadis, so in Flynn’s mind there was a natural split. It followed that the minimal price Russia would ask in joining the war was suspension of the sanctions and, in all likelihood, concessions on Ukraine.

When Flynn visited Moscow and met with Russian President Vladimir Putin two years ago, it is likely that as a private citizen he expressed these views to Putin. Flynn would not have to be bribed by the Russians as some analysts think. An American-Russian coalition working together to crush IS, and perhaps even the Taliban, was already on Flynn’s mind. He saw the Islamist wars as the greatest challenge to the United States, and he knew the U.S. needed help. He regarded sanctions and even some concessions on Ukraine to be a small price to pay to get it.

Trump’s administration is divided on this. Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson both have announced support for continued sanctions, and Mattis named Russia as a key adversary. In other words, two foreign policies were emanating from the Trump administration. One tracked former President Barack Obama’s strategy of two adversaries, while the other – Flynn’s – had a single main adversary: It was all about Islam.

Undoubtedly, Flynn floated this in Moscow years ago. When he was appointed national security adviser, the discussion began in earnest. The problem was not that he was bought by the Russians, but rather that in his obsession with IS, he failed to keep his own team aware of what he was talking about with the Russians. That is far more likely than having a secret arrangement with the Russians, because if he did, the Russians would not have let him make multiple phone calls in one day. He’d be too valuable to burn like that.

My guess is that he thought he had a green light on this, or simply thought that as a national security adviser, his job was to make strategy. When Mattis and Tillerson got wind of it – because all calls to Russian officials in Washington are intercepted – they blocked him.

The real problem is not that he spoke to the Russians or visited Moscow. There was no secret deal. Rather, the problem was that he tried to execute a radical shift in strategy that was actively opposed by senior officials. When they heard what Flynn was doing, they went ballistic. To put it another way, Trump shut down an attempt by Flynn to bring the Russians into the IS war. And Putin did not escape the sanctions.

I was in Dubai this weekend, had many conversations and said many things that addressed sensitive issues. Everyone understood that I spoke for no one but myself. If someone were mad enough to give me an official position (and I were mad enough to accept it), all the things I said when I didn’t matter would be remembered by decision-makers. All that would be fine unless I tried to execute a policy without asking anyone. I think, but don’t know, that this is what happened to Flynn.