By Xander Snyder

King Salman of Saudi Arabia visited Malaysia on Feb. 26, the first trip to the country for a Saudi monarch in over a decade. In his tour through Asia, he also will visit Brunei, Japan, China and Indonesia. Jakarta has not received a formal Saudi visitation in nearly five decades. The king’s decision to tour infrequently visited countries did not come out of nowhere – it was driven by Saudi Arabia’s increasingly challenging economic situation. He is trying to find more capital to sustain the regime and went looking for it in Asia in the form of participation in Saudi Aramco’s initial public offering (IPO).

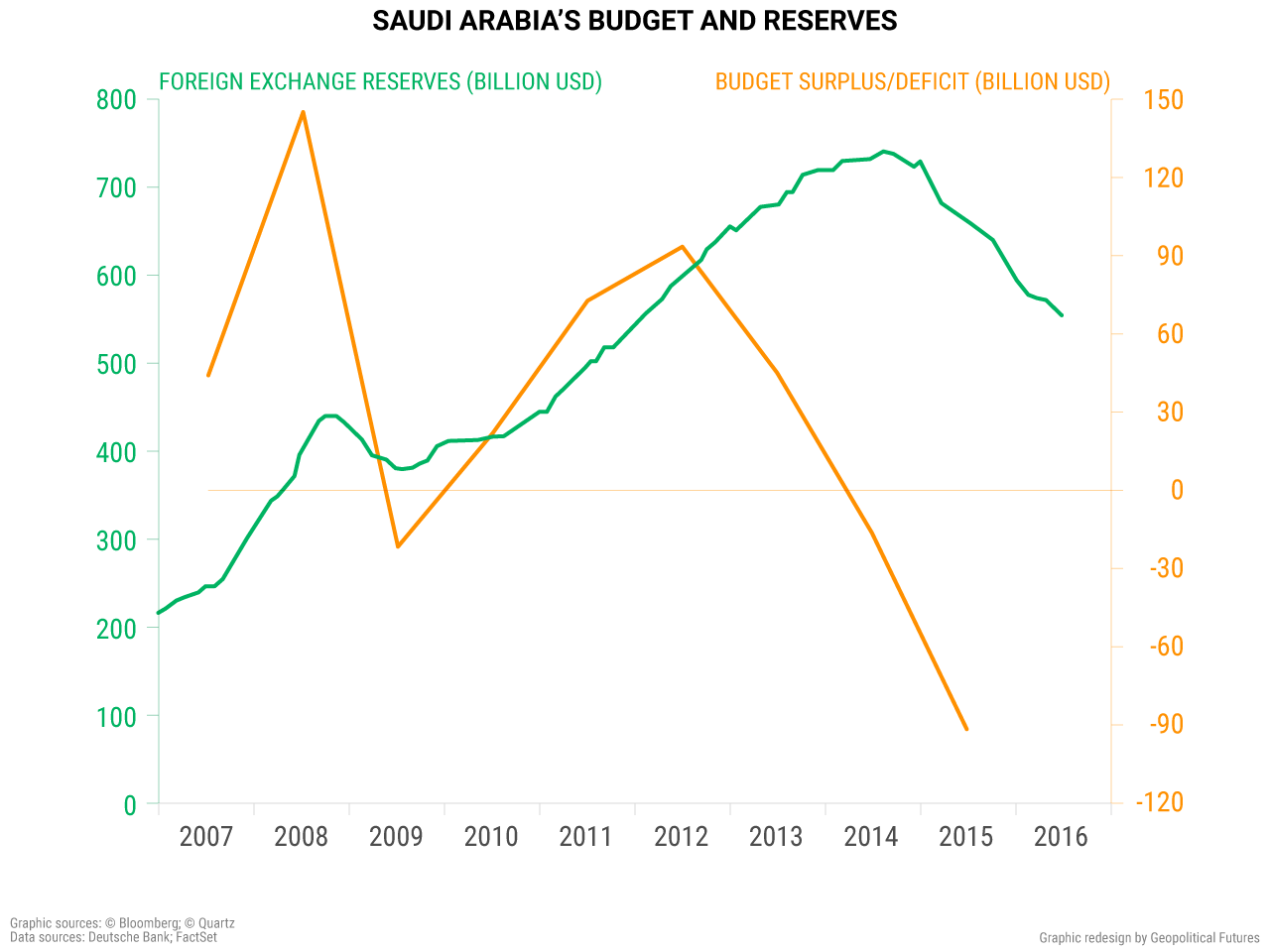

Saudi Arabia is a petro-state. The nation’s major oil company, Saudi Aramco, is the source of the country’s oil wealth, which is funneled to the royal family and subsequently the state. The state is highly dependent on oil revenues, with the petroleum sector accounting for approximately 87 percent of its 2015 budget. Depressed oil prices mean there’s less money available to pay for social programs and subsidies for commodities that are funded by oil revenues. This has put the regime in a dangerous position. Stopping payment on social spending risks creating a crisis of confidence among elites, which would challenge the regime’s position and the country’s stability. Saudi Arabia has so far avoided this problem by digging into its foreign exchange reserves, but these continue to fall and won’t last forever.

In an attempt to bring in additional capital to refill the state coffers, King Salman last year announced that Aramco would be going public. The ruling family had resisted an IPO since Aramco was fully nationalized in 1980. The regime wanted to avoid this because an IPO entails disclosure requirements, which would make Aramco’s operations more transparent. Selling shares also represents a small step toward the royal family beginning to lose control of the company. But harsh economic realities have forced its hand, and Saudi Aramco will now seek capital for up to 5 percent ownership of the company, a large enough share to bring in cash proceeds and small enough for the royal family to retain control. That King Salman personally traveled to Asia to seek investment from Saudi Arabia’s key customers is a sign that the kingdom really needs the money.

Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak (R) talks with Saudi Arabia’s King Salman (L) during the signing of a memorandum of understanding between the two countries in Putrajaya, outside Kuala Lumpur on Feb. 27, 2017. King Salman is on a four-day visit to Malaysia to reaffirm relations and boost economic ties between the two countries. MOHD RASFAN/AFP/Getty Images

Given the lack of detail known about Aramco’s finances, it’s difficult to determine how much a 5 percent equity sale will actually represent in dollars. Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman claimed that the company will be valued at $2 trillion, but these statements need to be taken with a grain of salt since the royal family obviously has a vested interest in inflating the company’s value. Wood Mackenzie, a consultancy group, estimated that Aramco may only be valued at $400 billion (this excludes the company’s downstream business). If Aramco does sell 5 percent of stock, this leaves a wide range of potential capital that may be raised by the IPO from $20 billion to $100 billion.

Aramco’s operations are not widely publicized, and the royal family wants to keep it that way. This explains the turn to Asia – while Saudi Arabia would like to have investment capital from the West, it knows it would come at a high price (greater transparency) that the kingdom isn’t willing to pay. While Aramco could float some of its shares on the Saudi Arabian stock exchange, the sheer size of Aramco’s IPO – which could be the biggest in history depending on the final valuation – means it will need the support of other stock exchanges. The Hong Kong Stock Exchange has already begun to court the bankers leading the process. Some Asian stock exchanges are less stringent than U.S.-based ones, and seeking capital in parts of the world with fewer disclosure requirements would suit the royal family just fine.

Saudi Arabia’s Asian customers have a vested interest in keeping Aramco up and running. Japan, a country notoriously dependent on foreign resources, imports 34 percent of its oil from Saudi Arabia, making Riyadh Japan’s biggest supplier. Saudi Arabia is also the largest exporter of oil to Indonesia and China, which receive 28 percent and 16 percent of their oil imports, respectively, from the kingdom. These three countries are economically vulnerable to Saudi Aramco’s – and therefore Saudi Arabia’s – financial problems. If they end up committing capital to Aramco’s IPO, it won’t be because they’re seeking investment yield. They must keep the supply of oil flowing, and if that means kicking up some cash now to do it, there’s a good chance they will.

While the rate of Saudi Arabia’s sale of foreign currency declined from 2015 to 2016, it still burned through $80 billion last year. In 2015, it went through $116 billion. In December, its foreign exchange reserves declined by approximately $2 billion. Although this is far less than the $10 billion drop it saw in October 2016, the trend of decline nevertheless continues. At the 2016 annual rate, a best-case valuation scenario would provide the kingdom with about a year of additional time before its reserves run out. Saudi Arabia may be gambling on a resurgence in oil prices, but even if this did happen it wouldn’t fix the challenge that the kingdom has limited productive alternatives from which to generate revenue to fund social payments. In 2015, the International Monetary Fund predicted that if oil prices did not recover, and Saudi Arabia could not reduce its state expenses, the kingdom would empty its foreign exchange reserves by 2020.

King Salman’s tour isn’t important in itself, but the underlying imperatives that caused him to feel compelled to make these visits personally are. Saudi Arabia is currently facing struggles that are a result of a political economy built on a shaky foundation that’s hardwired in petroleum exports, and seeking a one-time cash infusion alone will not solve its problems. The kingdom is a house built on sand.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East