By Jacob L. Shapiro

China and Russia conducted a six-day military exercise last week. The exercise simulated attacks on both countries from ballistic and cruise missiles. The Chinese Ministry of Defense declined to identify which country was the simulated aggressor in the exercise, but it’s not hard to figure out that it was the United States.

A few days into the exercise, the Trump administration published its National Security Strategy. The document is 68 pages long, but one line in particular from the second page has been quoted endlessly in the media: “China and Russia challenge American power, influence, and interests.” These two developments raise the same question: Is a Sino-Russian alliance emerging?

Military cooperation between Russia and China has indeed increased in recent years. The two main vectors for this cooperation have been weapons purchases and military exercises. Since the end of the Cold War, China has been the Russian weapons industry’s largest and most consistent customer. One of China’s more recent and consequential acquisitions from Russia, S-400 surface-to-air missile defense systems, are set to be delivered to Beijing in 2018. China’s current SAM force has a range of only about 185 miles (300 kilometers). The S-400s will have a range of 250 miles. This will put all of Taiwan within range of Chinese SAMs and will extend China’s range in the East and South China seas.

Soldiers in action during a drill on day three of the China-Russia counterterrorist Cooperation-2017 on Dec. 5, 2017, in Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of China. VCG/Getty Images

Soldiers in action during a drill on day three of the China-Russia counterterrorist Cooperation-2017 on Dec. 5, 2017, in Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of China. VCG/Getty Images

China and Russia have also stepped up the frequency, and complexity, of joint military exercises. They held their first joint exercise in 2003. Since then, the two countries have conducted nearly 30 military drills together. The most recent exercise, which tested readiness to combat an attack from a more advanced air power, was as much for show as it was to hone technical capabilities. The same can be said for Russian-Chinese naval drills held in the Sea of Japan back in September. Chinese state news agency Xinhua insisted that the exercises were not linked to North Korea, but considering the timing and location, that’s a dubious claim. That both drills coincided with U.S.-South Korean-Japanese drills is further evidence of their political nature.

Superficial Alliance

Many observers view these developments as signs of a nascent Russian-Chinese alliance. And both Russia and China want observers to think precisely that. Just take the recent anti-missile exercise. Russia’s ambassador to China made a point of telling Russian reporters last week that the exercise was an example of “vigorously developing military cooperation.” The subsequent article based on the ambassador’s remarks, published in Russian media, was picked up and posted verbatim on the only official English-language military news website of China’s People’s Liberation Army. It’s an article that, frankly, is difficult to take seriously. After the early headline-grabbing quotes, the story lists the areas where China and Russia are increasing cooperation: “military medicine, martial music, and military orchestras.”

Military cooperation, even over such weighty matters as military orchestral arrangements, does not guarantee, or even imply, an alliance between two countries. An alliance is a relationship of serious gravity. When two countries forge an alliance, it means their interests are aligned. In practical terms, that means they will put aside small-ticket items and points of contention because there is a larger shared interest that is of immense importance. The currency of an alliance is trust. The products of an alliance are duty and obligation. Alliances are not entered into lightly, nor are they broken easily. They are based on shared interests that are clear to both sides, interests important enough that they justify the sacrifice by the people of one country for the people of another should a threat arise.

This is not the basis of the Russia-China relationship, and it cannot be the basis of a Russia-China alliance. This is not to say that Russia and China don’t have some basis for cooperation. Both countries chafe at the extent and application of U.S. power. Russia and China are land-based powers of continental size whose access to the global economy can be significantly curtailed by the U.S. Navy in the event of conflict. U.S. power is uniquely suited to limit Russian and Chinese ambitions. For instance, Russia’s primary imperative is to extend its influence out to the Carpathians. The U.S. is blocking Russia from achieving this. China seeks to conquer Taiwan to make the South China Sea a Chinese lake. The U.S. stands in the way. China and Russia share an enemy, and that means a certain level of coordination is useful.

The Multipolarity Myth

When Russian and Chinese leaders get together, one of the buzzwords they use to discuss their policies is “multipolarity.” Multipolarity is part wishful thinking and part strategy. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the world has been unipolar – that is to say, only one country has had the ability to project global power: the United States. Russia and China would see that changed. That is where Russia and China’s shared vision begins – but it’s also where it ends. Russia and China agree that the U.S. should not be a dominant superpower. But they have a vastly different sense of what the alternative reality should be. Russia sees the alternative as a rebirth of Russian power on the order of the Soviet Union’s. China sees the alternative as reclaiming the mandate of heaven, a position that was usurped by Western imperialist powers in the 19th century at a period of maximum Chinese vulnerability. Their issue is not with a unipolar world. Their issue is that they themselves are not the ones calling the shots.

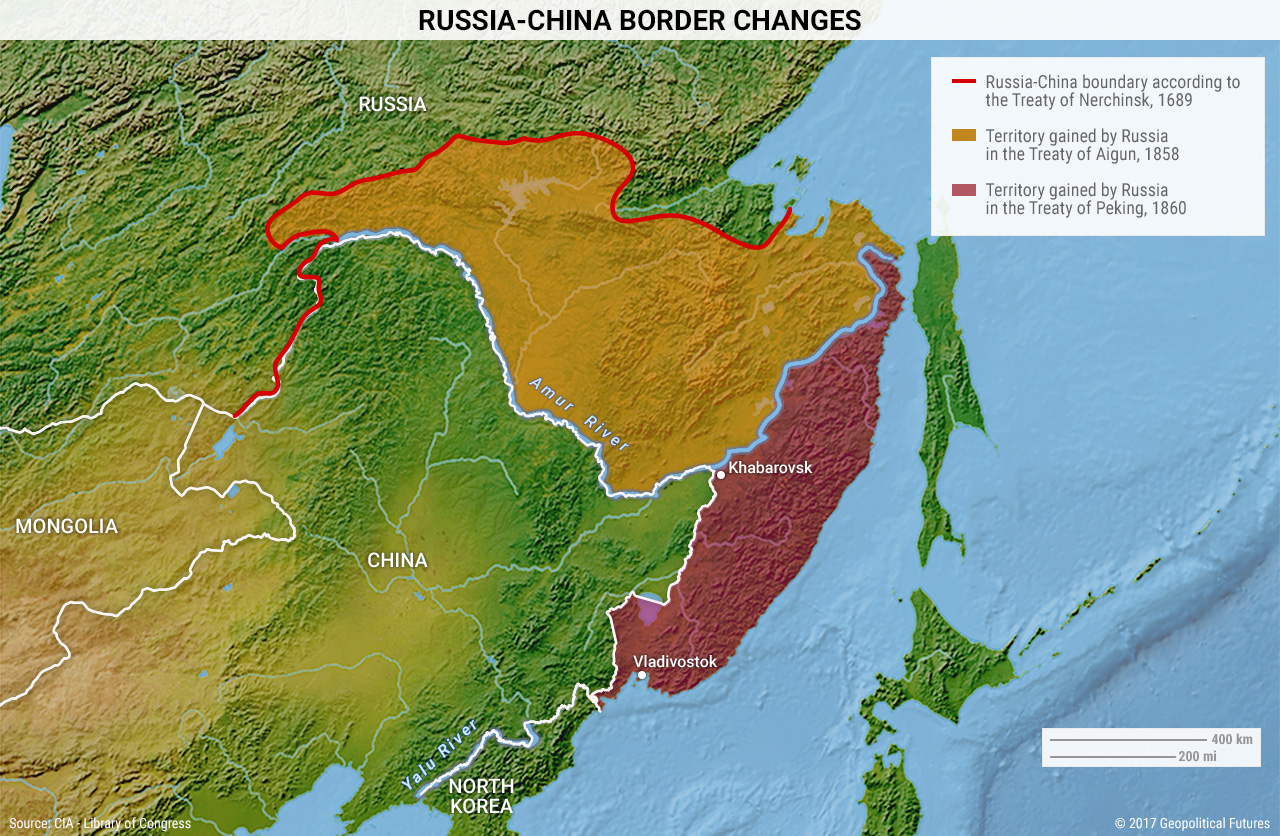

The two sides use the word multipolar to paper over this difference. Better to focus on weakening the U.S. now and work out differences later. But there is only so much that can be papered over. After all, from Beijing’s perspective, Russia was one of the Western imperialist powers that took advantage of Chinese vulnerability. Vladivostok is the most important city in eastern Russia, the home base of Russia’s Pacific Fleet – and China views Vladivostok and the roughly 350,000 square miles of territory around it that it was forced to cede to Russia in previous centuries as Chinese land. Russia views Central Asia as part of its sphere of influence. China views Central Asia as crucial to its plans to develop its own interior and to find alternate routes to Europe until its military is capable of challenging the United States.

From Russia’s perspective, China is a Pacific-facing power whose fundamental interests lie outside of Russia’s interests. Russia has also always seen China as lacking a basic sense of strategy as it is understood in the West, and Moscow believes that this lack of strategy, along with China’s internal inconsistencies, limits China’s effectiveness outside of its main wealth centers on the coast. From China’s perspective, Russia is part of a bygone world order that it seeks to rearrange to its own benefit. China’s patience is as long as its memory. China has not forgotten the various humiliations it was forced to endure, whether U.S. support of Chiang Kai-shek in the Chinese Civil War or Russia playing all sides during the Second Opium War to solidify its position in Asia at China’s expense.

Russia and China don’t trust each other, and they don’t trust each other because they have divergent interests. They work hard to keep this mutual distrust out of public view: military cooperation, economic investments, a chummy relationship between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, and promises of coordination on China’s grand plans to unify the world via belts and roads all serve to make it appear that the two sides are in lockstep. But these are surface-level political affairs of convenience. Russia and China challenge U.S. power, security and interests, but they do so for vastly different ends. It will be their undoing.