By Jacob L. Shapiro

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) says its members have approved a plan to cut oil production by about 1.2 million barrels per day, or roughly 1.5 percent of current global crude production. According to OPEC’s secretary-general, some non-OPEC countries have agreed to cut production by an additional 600,000 barrels per day, and Russia’s Energy Ministry said in a briefing that Russia would account for half of that, which would be gradually cut over the first half of 2017 “as technical capabilities allow.”

Oil prices “surged” around 8.5 percent in response to the deal, which is to say they recovered from cratering the previous day. On Tuesday, Saudi Arabia showed no signs that it was willing to abandon the strategy it has followed since 2014 unless both Iran and Iraq agree to cut production. Iran’s oil minister said his country has no intention of cutting output. As a result, the price of crude (West Texas Intermediate) dropped almost 5 percent. The public negativity around the potential agreement turned out to be a negotiating tactic in this latest round of horse-trading, but it should not be lost in the euphoria surrounding the deal that just two days ago some were seriously suggesting that oil at $25 a barrel was a realistic possibility. Oil prices have increased by only about 3 percent from where they started on Tuesday as of this writing. Had OPEC failed to come to an agreement, prices likely would have nose-dived. The deal is a measure of just how weak OPEC, and countries dependent on oil exports in general, have become.

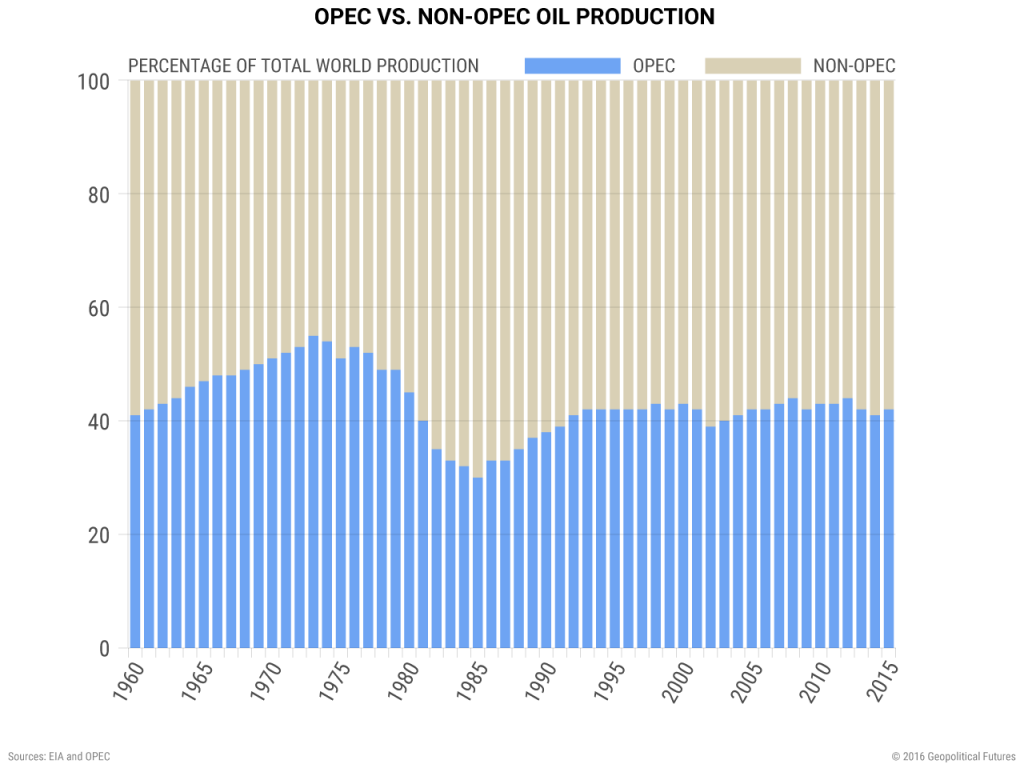

During its prime, OPEC was a mighty force to be reckoned with. In 1973, when OPEC proclaimed an oil embargo following U.S. support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, OPEC produced about 55 percent of the world’s oil, and its various member countries were rich in petrodollars. OPEC is still a significant player on the market, but it no longer possesses the dominant position it once did. Today it accounts for roughly 40 percent of global supply. The three major oil producers in the world now are Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States, which together produce almost as much as all 12 OPEC member states combined. In addition to having seen its market share decrease by almost a third since the heady days of the 1970s, many of OPEC’s oil-reliant economies are facing severe struggles, Saudi Arabia most of all.

That last fact is in many ways the most important. It is in the interest of OPEC states to cooperate with each other to drive up the price, because current prices are woefully inadequate for most member states. According to the International Monetary Fund, the fiscal break-even price for countries like Algeria and Saudi Arabia is around $100 a barrel. This is true for important non-OPEC states like Russia as well, whose finance minister said earlier this year that Russia could balance its budget if oil was around $82 a barrel. The problem is that once a few major oil producers cut production, it leaves an attractive opening that other OPEC members often rush to fill – agreement or not. Multiple studies have proved that OPEC members cheat on agreed upon quotas, and that this happens whether prices rise or fall. The only thing that changes is who cheats and why – the cheating itself is always present. With nationalism rising throughout the world, these governments are now even more pressured to do what is best for their countries, not the cartel.

As if to emphasize this point, OPEC reports two sets of official numbers for oil production by its members: one based on direct communication, the other on secondary sources. Based on the numbers released at the OPEC meeting on Wednesday, it would seem that the direct communication figures were used, which were conveniently higher than production figures confirmed via secondary sources. That means that even if all OPEC member states abide by the production caps, it could be relatively meaningless because they inflated the starting point.

The problem with OPEC, as with many international organizations, is that no enforcement mechanism exists beyond Scout’s honor. There is no way to ensure OPEC countries live up to their end of the bargain, and less so with non-OPEC states like Russia. There is no global oil police force capable of dishing out punishment to those violating agreed upon rules. Many of these countries are struggling economically and see those struggles manifest in serious political and social problems within their own societies. They have every reason not to trust each other and no compelling reason – beyond being similarly up the creek – to cooperate.

Saudi Arabia’s energy minister, Khalid al-Falih, front right, attends a meeting at OPEC headquarters in Vienna, Austria, on Nov. 30, 2016. JOE KLAMAR/AFP/Getty Images

The other factor to consider is that OPEC and Russia do not necessarily want the price of oil to rise too high. Saudi Arabia has been the focus of some derision for its covetous desire to protect its market share, but the Saudis didn’t insist on it out of greed, but rather necessity. The shale revolution has fundamentally reshaped the oil market. The U.S., for example, does not have a great deal of spare capacity the way it traditionally has been defined. OPEC still has far more spare capacity than any country or grouping of countries. But a number of drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) in the U.S. can be leveraged in a relatively short period to produce oil if high prices are sustained.

Saudi Arabia and other major oil producers are caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, they need oil prices to increase to stabilize their economies. On the other, the more the price rises, the more investments will target developing non-OPEC sources of crude oil. The price at which this happens may not be as high as it once was. Renowned oil analyst Daniel Yergin has noted that while the price of oil used to have to range between $60 and $80 a barrel for U.S. shale companies to be viable, that range now is $40 to $60. The most recent data available from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) bears this out. U.S. crude production has decreased by roughly 500,000 barrels per day in the past year, but what is striking about that figure is that it didn’t decrease more during a time of such intense downward pressure on the price of oil.

Last September, the EIA began providing detailed estimates of the number of DUCs currently in the U.S. According to the EIA, over 5,000 such wells exist in the U.S. According to IHS Energy, between 2,500 and 3,000 of those are located in highly productive oil regions. Bringing 150 of these wells into production each month could increase production by 200,000 barrels a day. Currently, EIA projects U.S. oil production will increase by 110,000 barrels a day in 2017. But if the OPEC agreement is enough to buoy the market to a higher price, and OPEC’s members and non-members abide by the terms of the agreement, that number could be revised upwards. Norway and Brazil are two other countries that have seen oil production increase in 2016, and they could, in a limited way, potentially increase production in 2017.

The issue comes down to three basic realities. The first is that there is no guarantee that OPEC member states and sympathetic non-OPEC partners will abide by their agreements. An exception already has been made for Iran, which is allowed to increase production by 2.2 percent. Indonesia could not agree because as OPEC’s only net importer of crude, it is a fan of low oil prices (its membership is now suspended). Other exceptions and objections may yet come. The second reality is that OPEC can no longer shape the market like it used to, and increased prices are a double-edged sword of higher oil revenues on the one hand, and opportunities for other non-OPEC states to steal market share on the other. The third reality is that for many of these countries, the time they can afford to give up current revenue to boost future revenue is limited, because their economic struggles are here and now. If the market’s fairly tepid reaction to Wednesday’s “unprecedented” agreement is an indication of future sentiment towards this agreement, it may be crippled before it starts.