By George Friedman

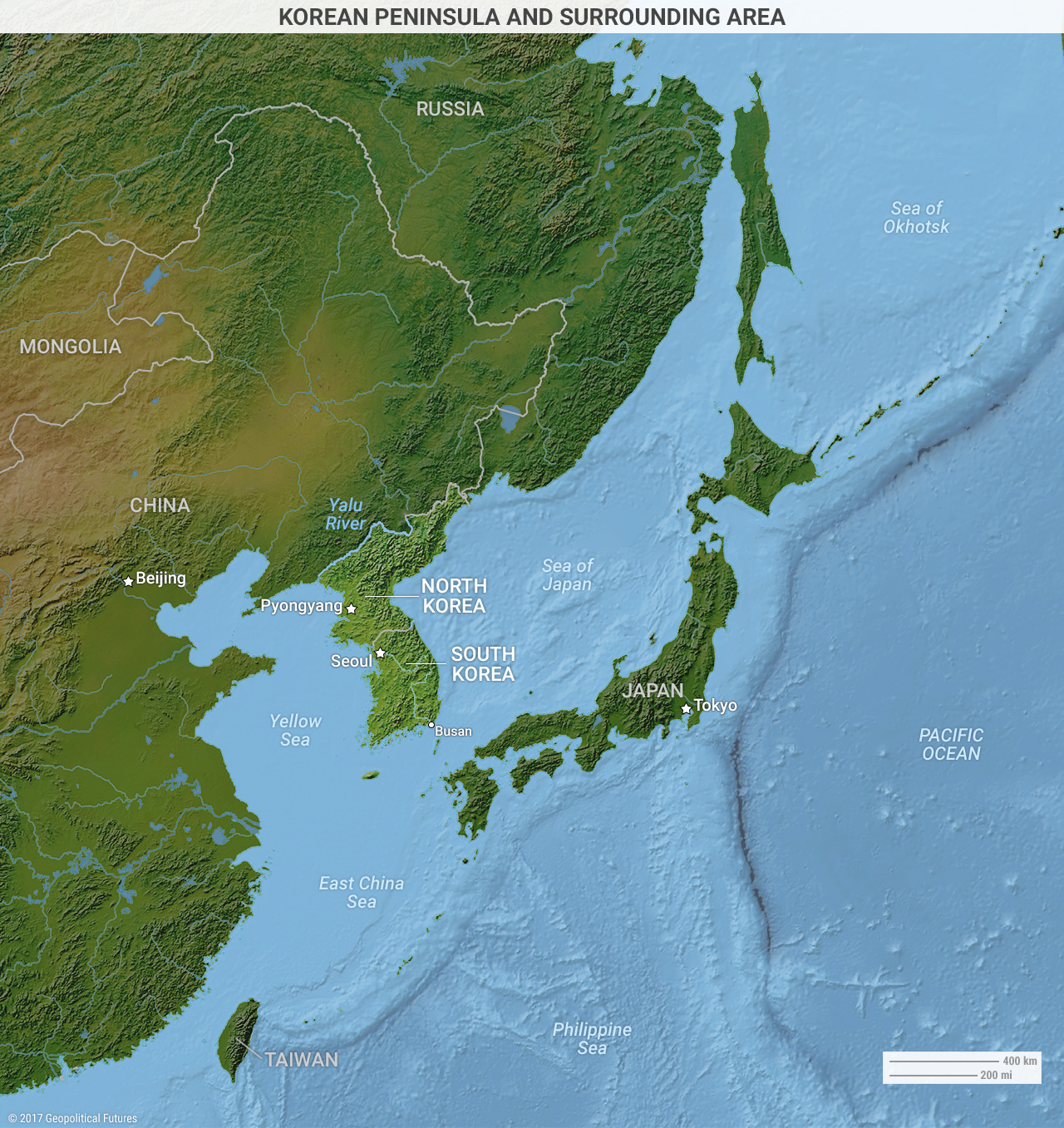

The assumption about North Korea’s nuclear program has been that it is primarily needed for regime preservation. North Korea has been perpetually concerned about an American intervention, along with other threats. It sees Japan as a potential enemy that has attacked and occupied Korea before. It also has historical animosity toward Russia and China. The Soviets supported the North Korean invasion of the South but when North Korean forces faced American forces, and crumbled, the Soviets avoided taking risks on North Korea’s behalf. China similarly was unwilling to intervene in support of North Korea until U.S. forces neared the Yalu River and threatened China. The North was subsequently devastated as the United States and China used it as an arena to fight their war. Finally, North Korea has viewed South Korea as a U.S. proxy, bound to the United States by treaty and national strategy.

From the North Koreans’ point of view, they live in a tough neighborhood, filled with threats former and current and with putative allies that did not raise a finger to help North Korea in times of need. Some of these threats emerged long ago, from the American perspective. The Korean view of history has a longer time frame. The view that the North Koreans wanted a nuclear weapon to guarantee their national security seemed accurate and seemed to forecast the American response: taking steps to prevent a nuclear North Korea. But the situation has become more complicated than that.

Shared Views

Seoul saw a potential American strike on Pyongyang as a direct threat to South Korean interests. The ability of North Korea to impose a massive bombardment on South Korea’s capital was a risk the South couldn’t accept. What’s more, it wasn’t obvious that South Korea and the United States, acting together, could mitigate the threat. South Korea, therefore, resisted any American military operation. Japan continued to maintain a more aggressive attitude toward North Korea. South Korea saw China and Russia as pretending to mediate, while in fact both were content to see the U.S. get bogged down in the Korean Peninsula.

In this sense, the North and the South had similar views. The United States, Japan, China and Russia each had their own interests and each saw the Korean Peninsula today as serving the same purpose it served decades before. For them, it was an arena for playing out their own national ambitions and fears. The North Koreans had always felt this way. The South Koreans, however, were comfortable with their relations with the United States and its military guarantees. But the value of those guarantees had changed with the threat of a pre-emptive strike.

The placement of massive artillery, ancient as much of it might be, north of the Demilitarized Zone was in retrospect a brilliant move. Artillery does not have to be state of the art to hurl explosives for miles. Large concentrations of fortified artillery are difficult to destroy, and Seoul’s position so close to the border makes it an easy target.

Artillery also compelled South Korea to rethink its view of North Korea as its primary adversary. Instead, it began to see the North as a country with a shared basic interest. The devastation of the Korean War is seared into both countries’ memories. It led North Korea to develop a nuclear capability. It led South Korea to refuse to participate in an attack on Pyongyang with the primary aim of destroying its nuclear capability. They both have an interest in not permitting the peninsula to become a battlefield again.

The issue now is how far this joint vision goes. Each has fears of the other. The North is poor and oppressive. The South is economically vibrant. The North sees South Korea’s economic well-being and culture as a threat to the authority of its regime. The South does not intend to be conquered by the North.

A Basis for Cooperation

The two states, however, understand that the logic they have been following necessarily leads to different outcomes. If the primary goal is to exclude third parties who might wage war or be sanguine about a war being waged, then neither state can allow itself to be drawn into these foreign ambitions. And if that is the case, then each must find a degree of trust in the other, and a basis for cooperation.

North Korea seems to have seen this most clearly, or at least it has a more immediate interest in splitting South Korea from the United States and, to a lesser extent, from Japan. Pyongyang would like to see South Korea’s refusal to allow a strike on the North expand into a rupture, particularly when it comes to defense, between Seoul and Washington. Forcing the United States out of the Korean Peninsula is unlikely. But it is a goal shared by China and North Korea. To an extent, this is a replay of 1950.

For South Korea, ejecting the U.S. from the peninsula carries enormous risks. It is North Korea’s task to make those risks seem far less dangerous than the risk of war. North Korea cannot pretend to abandon its regime nor can the South Koreans pretend to abandon theirs. The logical outcome is for North Korea to propose some agreement in which the two Koreas maintain separate regimes and political orders, but act toward the rest of the world with some unity.

The North’s fear of the South’s economic dominance and the South’s fear of being subjugated by the North likely make any such entente impossible. But there are major powers, namely China and Russia, that would give a great deal to see the U.S. expelled from the Korean Peninsula. That would shift the balance of power in the Northwest Pacific dramatically. Of course, South Korea – and North Korea – would not want Russia and China to operate in the region without fear. Worse, their old enemy Japan would now have to rearm and that would resurrect a historic nightmare.

Unless the North or the South dramatically reforms their regimes, it is difficult to imagine an entente, or South Korea breaking its alliance with the United States. And using a nuclear threat against the South would cement that relationship. Still, it is worth trying from the North’s point of view, and worth considering from the South’s. The near nuclear capability gives the North opportunities it did not have before. But South Korea is an industrial democracy of the first order, and North Korea is not, to say the least. But having split South Korea and the United States on pre-emptive strike, the North has nothing to lose in seeing how far reconciliation between Pyongyang and Seoul can go. And China and Russia can only be smiling, while Japan must be contemplating its own nuclear plans.