By Xander Snyder

Last week, North Korea conducted yet another missile test, and yet again the world clutched its pearls in horror. The thing is, North Korean weapons tests are, by their nature, provocative, so we shouldn’t be too surprised when they incite condemnation among countries whose security they would impair. What is sometimes surprising, though, are what the reactions reveal about a country’s intentions – and therefore how that country means to use the North Korea crisis to its advantage.

Leverage

Russia is a case in point. On Dec. 5, Russia’s deputy foreign minister said Moscow was prepared to “exert its influence” on Pyongyang to resolve the brewing conflict. In fact, he had outlined a three-part strategy even before the missile test. The first part would require the United States to halt military drills with South Korea. North Korea would, in turn, stop testing its missiles. The second part would entail direct negotiations between North Korea, South Korea and the United States. The third part would involve a process where “all the involved countries [would] discuss the entire complex of issues of collective security in Asia.” The implication, of course, is that Russia would have a role in creating the agreement.

The deputy foreign minister’s proposals are hardly novel, but they raise some important questions. In what ways and to what degree does Russia have leverage over North Korea? What outcome would best advance Moscow’s interests?

The answer to the first question likely begins and ends with oil. Russia has long been suspected of supplying North Korea with oil (international sanctions limit such activity), but recent reports from a collective of journalists called Asia Press International claim that the price of oil there has fallen by 40 percent. We have not yet confirmed the amount of oil Russia has exported to North Korea, and so we have not verified the fall of the price of oil, but it’s easy to see why Russia would want to help Pyongyang. Doing so creates dependency, and dependency creates leverage that Russia could use in future negotiations with China or the United States.

Keeping the oil flowing, moreover, serves Moscow’s interests by helping to preserve the power of Kim Jong Un. Russia may not be a particularly close ally of North Korea, but its shared border means that its security is, to an extent, tied to North Korea’s. If Pyongyang and Washington go to war, how long would Russia tolerate the presence of U.S. troops so close to its border? How many North Korean refugees would it allow in its territory? The Kim regime, for all its faults, insulates Russia from the devil it doesn’t know.

This helps to explain why some 1,000 Russian marines are conducting live-fire exercises in Primorye, near Russia’s border with North Korea, according to the Russian Defense Ministry. Military exercises in Russia’s east are not unprecedented, but they are uncommon. (The last time Russia conducted military exercises in the Far East was February 2016.) The U.S. and South Korea, meanwhile, are conducting exercises involving 230 warplanes and 12,000 troops. For its part, China is performing naval exercises in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea, having alluded in a state-supported newspaper that South Korea could become a major rival.

Valid though Russia’s reasons for helping Pyongyang may be, Moscow’s peace plan suffers from the same flaw that every other proposed plan suffers: compliance. The U.S. wants North Korea to suspend its nuclear weapons program entirely. The only way to ensure that that happens is on-the-ground inspections to which Kim would never agree.

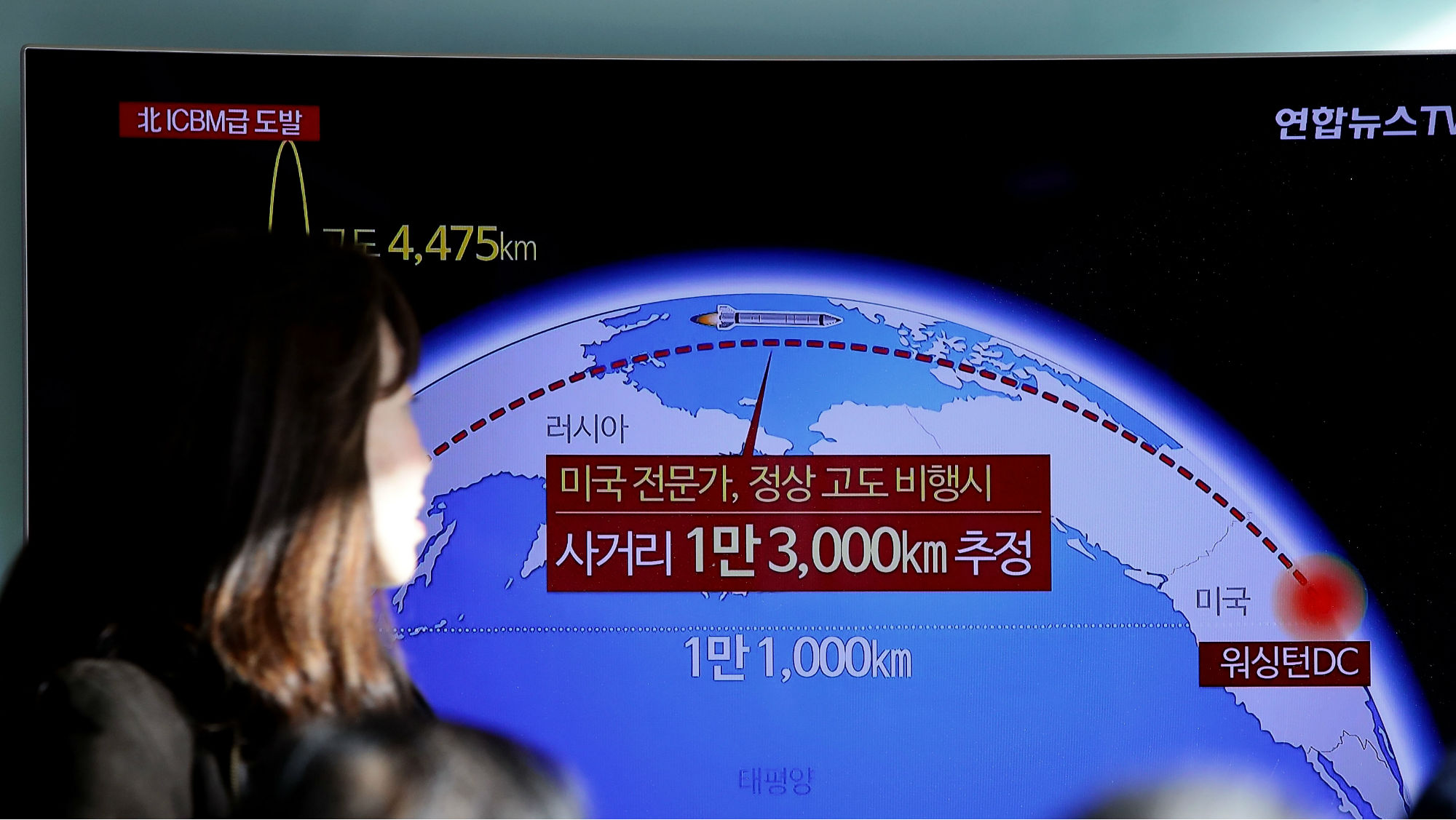

The plan also ignores North Korea’s technological advancement. It’s true that North Korea had not tested its missiles in more than 70 days, and it’s true that the U.S.-South Korean military exercises may be to blame for the tests’ resumption. But the most recent test showcased significant improvements in range and in deliverable payload weight. If North Korea can improve its missiles without live-testing them, then clearly a moratorium won’t arrest the program. The Russian proposal, if implemented, would fail to resolve this issue.

Damned If It Does, Damned If It Doesn’t

As for the United States, Washington has no good options. Failing to prevent North Korea from acquiring a deliverable nuclear weapon – which it can then use, with impunity, to make demands of its neighbors – undermines the credibility of the United States’ security guarantee in the Pacific. Executing a pre-emptive attack that forces South Korea into a war risks undermining the same credibility. A security guarantee isn’t a security guarantee if a country has to fight and die in a war it didn’t want.

Faced with this impossible situation, the U.S. has through some media leaks shown it is considering unconventional ways to disarm North Korea without invading it. On Dec. 6, two anonymous U.S. officials leaked details about a microwave weapon that could be delivered on a low-flying missile to destroy electronics that the North would need to launch its intercontinental ballistic missiles. Whether these technologies would work, let alone if they exist, is beside the point. Creating the appearance of viable alternatives gives the U.S. some maneuverability in a world full of red lines.

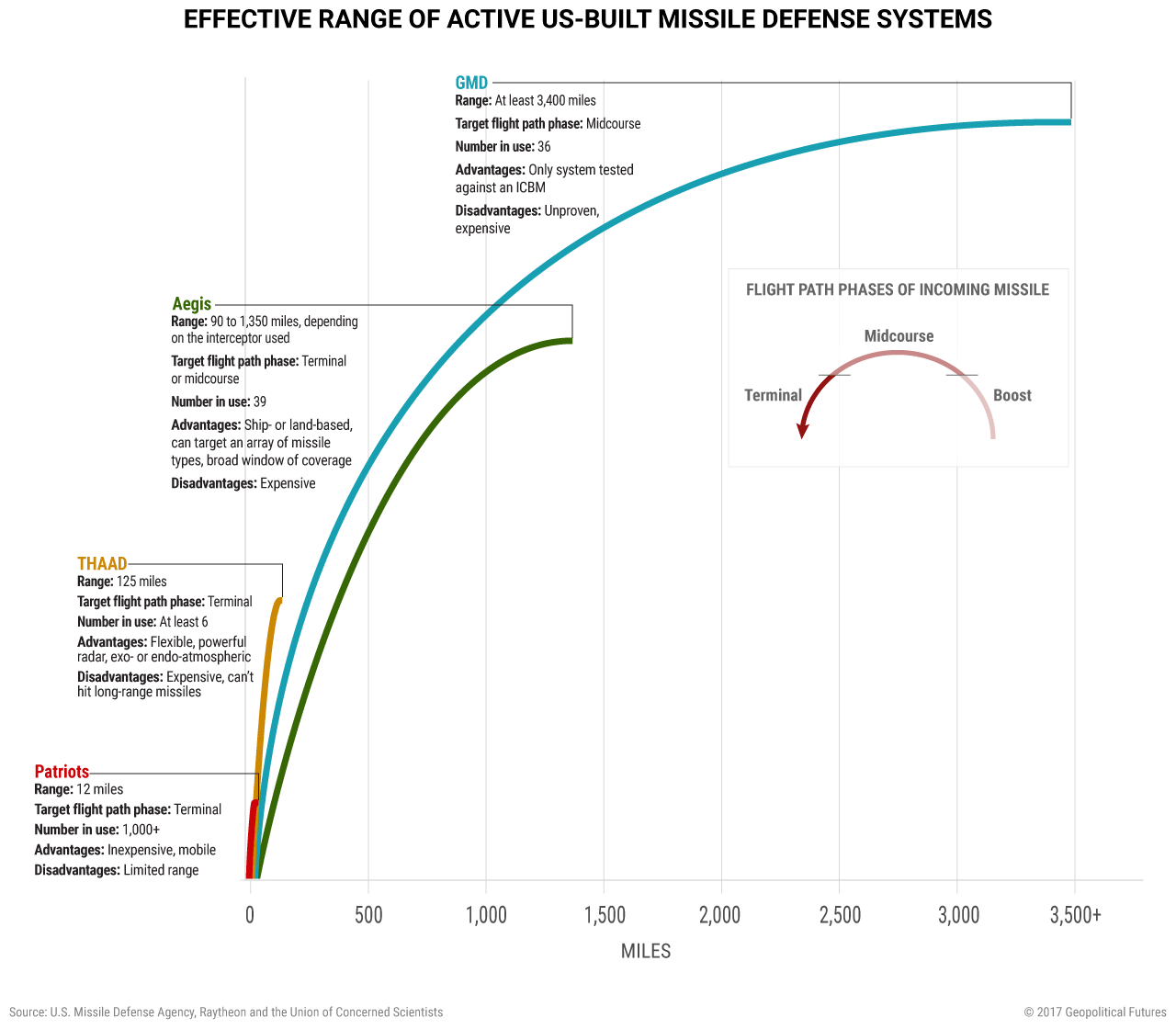

The U.S. is also focusing on ballistic missile defense, reportedly now scouting for additional locations on the West Coast to erect systems. But ballistic missile defense systems are simply not yet reliable enough to provide the surety needed to construct a dependable strategy around them. In fact, on Dec. 4, The New York Times reported that U.S.-supplied BMD systems may have failed as many as five times in preventing missile attacks on Saudi Arabia by Yemeni rebels.

North Korea will soon possess a deliverable nuclear weapon – if it does not possess one already. The speed with which it has developed its program has exceeded expectations, including ours. Some analysts believe Pyongyang will have one in only a few months. The window for U.S. intervention, if it even still exists, is rapidly closing. But even if the U.S. were to attack North Korea, there is no guarantee it would destroy the nuclear program entirely. And there’s nothing to stop the survivors from starting from scratch in the event their program were, in fact, annihilated. This time they would have even more effective propaganda to galvanize the public.

The United States, then, is damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t. It can bet the lives of soldiers on the uncertain prospect of taking out North Korea’s nuclear program. It can conduct a pre-emptive nuclear attack. Or it can live with a nuclear North Korea. It’s an unenviable position, to say the least.

The Road to 2040

The Road to 2040