By George Friedman

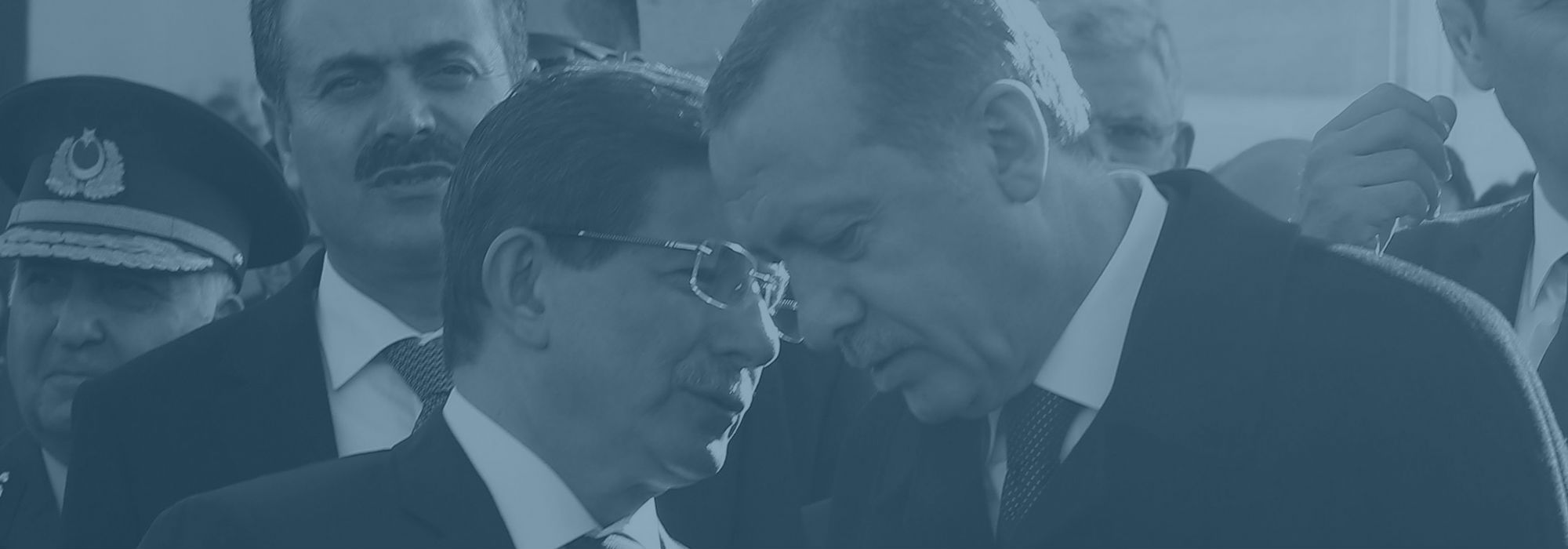

The recent resignation of Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu has been seen primarily as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s attempt to increase his power, concentrating it in the presidency. Inherent in this interpretation is the assumption that there were no vital policy issues dividing Erdoğan and Davutoğlu. That in turn is based on a reading of Erdoğan as primarily enhancing his power toward no end beyond increased power. Following this theory, Davutoğlu, a milder figure with far less ambition, was simply a pawn in Erdoğan’s game. Davutoğlu had ideas, but lacked the will to implement them. Politically, he was a non-entity.

Examining the personal characteristics of political leaders is a well-known pastime for analysts. It allows neutral observers to avoid thinking of what their real motivations are and for their political enemies to sketch a picture of evil. His supporters’ vision of the same man as a saint is always less compelling. In all likelihood, neither his enemies nor his supporters have known him long enough to have a qualified opinion, but at least that allows them to meet on a level playing field. Such analysis of political figures serves another purpose. By focusing on his personality and declaring it to be pathological, they can avoid the difficult task of figuring out what he is trying to do, by dismissing any motive beyond self-love. Self-love is always present in political leaders, as well as reporters. But in both, the motives are always far more complex. In the current circumstance of Turkey, it has to be more complicated.

Let’s consider the obvious. The Sunni Islamic world is being swept with an intense wave of both religiosity and political radicalism. Modern Turkey was founded as a militantly secular state nearly a century ago. It retains a substantial secular population and that population might have more weight if Turkey hadn’t been rejected by the EU. But it was. Therefore, the energy of the Sunni rising is a reality Turkey must address.

In addition, Turkey is a rising power. It has the second largest GDP in the Islamic world (behind Indonesia), as well as a substantial military. It is also a stable platform in the midst of instability. To its south, Syria and Iraq are in chaos. To the northwest, Europe is disrupted, to put it mildly. To the north, Turkey sees a Ukraine faced off with Russia. Each of these crises directly affect Turkey. The EU looks to Turkey to manage the Syrian refugees. There has been a military confrontation with Russia. The situation to the south is out of control. And for Turkey, the Kurds are seen as an internal enemy.

You therefore have a major power, surrounded by a sea of instability, facing a Sunni rising that excites Turkey’s population. In such a circumstance, Turkey must find a place in the Muslim world commensurate with its size and interests. Its interest is to stabilize the region, but to do that it must assert power into the former Ottoman regions. It is not yet in a position to do so. It will be a great power. It is not yet a great power. It must find an interim path.

Let me now speculate. Davutoğlu is a devout Muslim. As foreign minister, he saw the rising tide of the Islamic world, and having an academic bent, understood that the trend could not simply be crushed by Turkey, nor could the rising simply be excluded from Turkey. And Davutoğlu was not hostile to it. His goal was to protect the security of Turkey and shape the rising, particularly in the Arab world to the south. There was no one solution to this problem. Turkey was not going to go to war with these forces. Nor would Turkey simply acquiesce. It required a subtle approach in which support would be used to deflect the revolutionaries from Turkey and at the same time try to move it to mature.

Embedded in Neo-Ottomanism, the doctrine that Turkey will resurrect its imperial power in all directions, was a religious concept as well. Neo-Ottomanism and the caliphate are intimately bound together. Declaring the caliphate was hardly on Erdoğan’s agenda, but allowing Davutoğlu to shape the region was necessary. When the Islamic State emerged and declared a caliphate, Turkey could not endorse it, nor did it have the power to crush it. IS is not easily crushed, and the blowback in Turkey would be unpredictable. So Davutoğlu played an Ottoman game. He bought off IS with minimal contributions, but enough so that at a later day Turkey could dominate and reshape it into something still Islamist, but less barbaric. In spite of all American demands, the Turks refused to enter Syria or Iraq to wage war. It was militarily prudent and politically wise in their view.

The Russian intervention complicated their position dramatically. Russia is Turkey’s historical enemy. Russia’s presence to Turkey’s south and its position on the Black Sea place Turkey in the difficult position of handling Syria and Iraq and simultaneously facing a peer power. The downing of a Russian plane was meant as a warning. Turkey realized that Russia was not impressed, but wouldn’t respond with airstrikes. Moscow responded instead with aid to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which had been allied with the Soviets.

Then the Europeans approached the Turks to house refugees. The Europeans were afraid of IS members included among the refugees. So were the Turks. IS, sensing Turkey’s growing unease, had already attacked Turkish targets. And Turkey, relatively little money but the promise of a new deal with Europe, now housed an unknown number of IS operatives.

The situation was now out of hand. Davutoğlu’s strategy of managing the chaos had run afoul the Russian and Kurdish reality. In addition, the pressure from the United States to act on IS was becoming overwhelming. The United States appeared, for all its rhetoric, to be comfortable with the Russian presence in Syria. The U.S. wanted Bashar al-Assad gone, but not while IS still posed a threat to Damascus. The United States couldn’t protect Assad for political reasons, but the Russians could. The Americans and the Russians began exploring ceasefires together – not altogether harmoniously, but still together.

The Turks were now in a hole. To have the Russians hostile and the Americans neutral was untenable. The Turks reached out to Poland and Romania to seek a partnership as a gesture to the Americans and to demonstrate Turkish value. The United States was not satisfied. It wanted Turkey to intervene against IS directly with the United States. After that, considerations of U.S. support against Russia could be discussed. And once IS was dealt with, the question of Assad’s future – the Turks hate Assad – could be discussed.

Davutoğlu’s vision of managing and deflecting the Sunni rising, including IS, was in shambles. Turkey now had a Russian problem along with a Sunni problem. And it didn’t have the United States. It slowly tried to find a new balance but the United States wasn’t prepared for any balance that did not include intervention against the IS. I will further speculate that the U.S. was not comfortable with Davutoğlu. Erdoğan, pressed on all sides and long past thinking of a bloodless expansion of Turkish influence, removed Davutoğlu and began the difficult process of absorbing the cost of taking on IS with U.S. aircraft overhead and his troops on the ground.

Thus my speculation concludes. But we have seen the Turkish declaration on the Black Sea and the move into Syria. We have seen the talks with Poland and Romania. And we have heard the endless rumors of Turkey lightly supporting IS by allowing passage and facilities to sell oil. It builds a picture of a massive shift in Turkish policy to a policy in which Davotuğlu had no place. It surely involved Erdoğan’s ego, and his war on journalists has the smell of desperation. But Davotuğlu’s departure was odd indeed. I suspect there was a decision made that the situation was out of hand, the Americans were needed and the price had to be paid.