By George Friedman

The Pyeongchang Olympics are nearly over, which means the focus will soon return to the North Korean nuclear program. Somewhere along the way, the nuclear program went from being a crisis, likely to precipitate war at any moment, to being an issue of concern. There are thousands of issues around the world that governments are unhappy or uneasy about, but few rise to the level of garnering anything beyond public statements. Plenty of statements about the North’s nukes are still to come, but the sense now is that the core issue is settled and all that’s left is to define how the new reality works.

The Backdrop

Let’s begin by considering the geopolitical imperatives of the relevant actors.

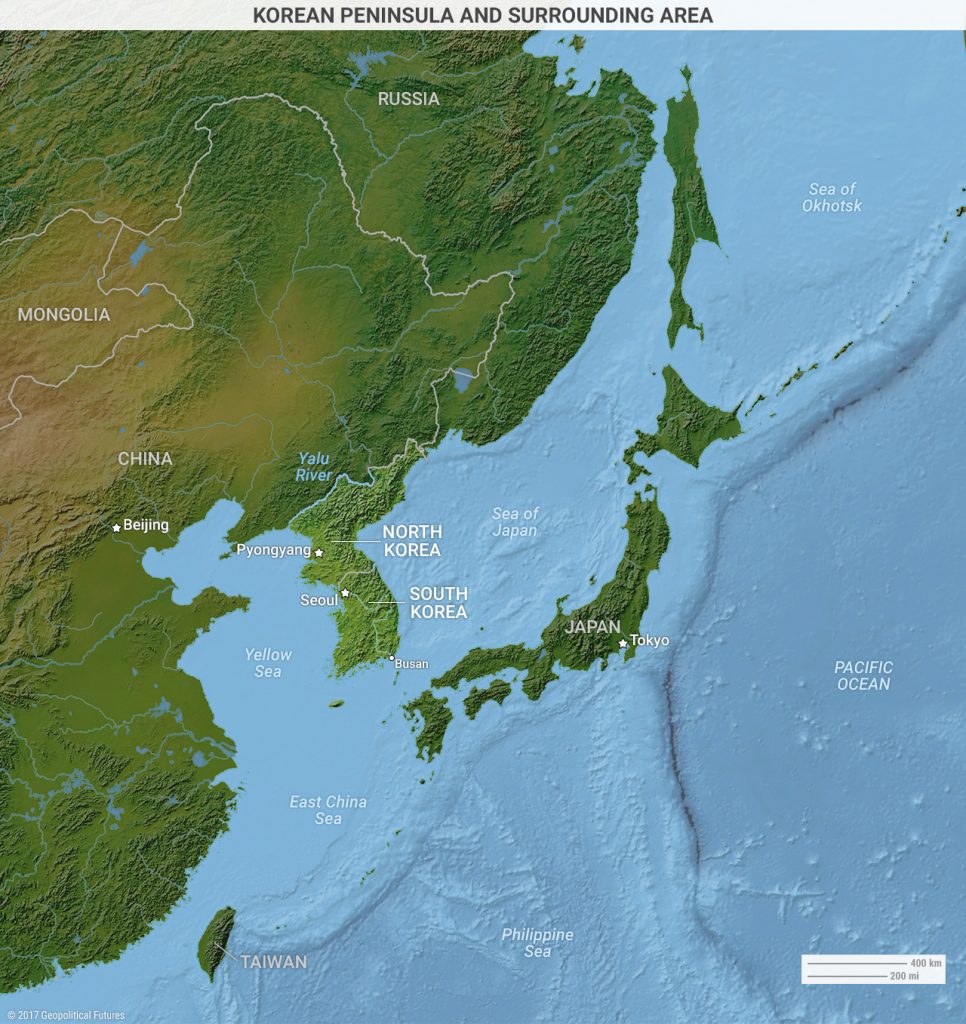

North Korea, like all countries, values its own preservation above all else. Next, it wants to unify the Korean Peninsula under its control, or at least get as close to that as it can. North Korea faces a series of threats. One is the United States, which is determined to block the North from dominating the peninsula. Japan feels the same. Russia and China are ostensibly on the opposing side, but Russia and China do not have many interests in common with North Korea except when it comes to frustrating or repelling the United States. The only reason either Russia or China would support the North’s ambitions would be to undermine the U.S. position in the Northwest Pacific. They will risk little but gladly reap the rewards.

South Korea’s imperative is to uphold its status as a leading industrial and technical power. It has no desire to see Pyongyang fall because underwriting the cost of North Korea’s reconstruction could cripple the South’s economy. Nor does it want a recurrence of the 1950-53 war, which is just another threat to its economic position. Seoul wants to have U.S. guarantees to deter North Korean adventurism, but it doesn’t want Washington to push too far and start a war.

The United States has an imperative to prevent North Korea from obtaining weapons that could strike the U.S. mainland. Washington also has an imperative to defend its position as the dominant air and naval power in the Northwest Pacific in order to contain China and Russia. U.S. bases in South Korea, as well as in Japan, are critical to this effort.

Japan’s imperative is to protect the homeland from nuclear strikes and maintain its maritime access to raw materials and markets. It also needs to prevent the emergence of a unified Korea, which would be a potential rival, forcing Japan to significantly rearm its military – possibly even to develop nuclear weapons if the new Korean state possessed nukes. Japan’s overriding interest is to have the United States defend it against North Korean attack and guarantee its maritime security.

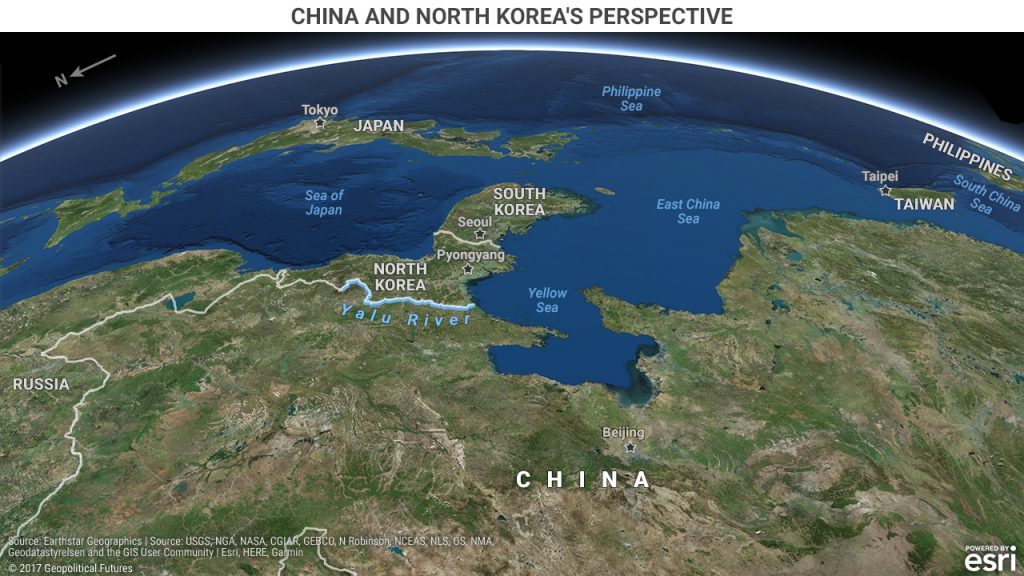

China’s overriding imperative is to gain control over the nearby seas. It is frightened by the prospect that the U.S. could blockade it, so excluding the U.S. from these areas – and from the Western Pacific altogether – would ensure that China has access to the global oceans for its trade. Beijing looks at events in the Korean Peninsula as potentially weakening the United States, and so it has no desire to try to resolve it – to varying degrees, every outcome is a win for China. If the U.S. strikes North Korea, China can portray the U.S. as an aggressor. If it doesn’t, it can portray the U.S. as weak. And if North and South Korea reach an agreement that limits the U.S. presence on the peninsula, or expels it completely, then China’s goals are met.

Russia has no overwhelming imperatives when it comes to the peninsula, save that anything that makes the U.S. appear weaker makes Russia look stronger.

The New Reality

The United States could tolerate North Korea’s nuclear program until it started approaching the point where it was a legitimate threat to the U.S. in early 2017. The U.S. was restrained, however, by South Korea’s imperative to avoid a war that would weaken the South’s economy. The U.S. turned to China to mediate an agreement, which of course failed.

With the United States’ threats drained of some legitimacy, North Korea could ease up. It slowed its effort to complete an intercontinental ballistic missile that could deliver a nuclear payload to the United States. Such a system would require extensive testing of both the missile and the nuclear weapons, and such tests cannot be hidden. So, at the moment, the North Koreans have not developed an ICBM that can threaten the United States, and they likely could not without showing their hand. This reduced the pressure on the United States to attack. Inadvertently, it also kept U.S.-South Korean relations intact, therefore not undermining the U.S. position in the region.

This also opened the door for North Korea to launch its diplomatic offensive, designed to draw the South into some sort of relationship that excluded the United States. It is hard to imagine what this would look like, but it would likely satisfy the South’s wish to avoid war and the North’s wish to diminish the U.S. presence on the peninsula. How the two Koreas could trust each other is of course a question, particularly when one is a nuclear power, but the alternative is hard for the South to accept – strikes against the North’s nuclear facilities triggering a massive artillery bombardment of Seoul and wrecking a great deal of the South’s economy.

The North has dangled the offer, and the South is intrigued. The U.S. can’t stand in the way without looking like a warmonger, but given that development of the North Korean nuclear and missile programs has apparently slowed, Washington has been willing to get out of the way. The issue will be whether the evolution of relations with the North will include an end to or radical modification of the U.S.-South Korea defense pact. Obviously, China would be delighted to assume responsibility for guaranteeing South Korea’s defense against the North, and it would likely be quite sincere. But then South Korea would face the prospect of its old enemy Japan rearming while the U.S. was searching for another country to anchor its strategy in the region. This would sow massive uncertainty, which South Korea doesn’t want.

Seoul will do almost anything to avoid a war, but the danger of an agreement with Pyongyang is that the South could find itself subordinate to the North. (South Korea is much wealthier and more developed, but North Korea has the nukes.) Since that is pretty much what the North wants, the question is what South Korea will do. In the long run, the risk of an agreement for South Korea is almost as great as the risk of war. There are too many unknowns for the South. And that means that this issue will likely become a crisis again before this is over.