By Xander Snyder

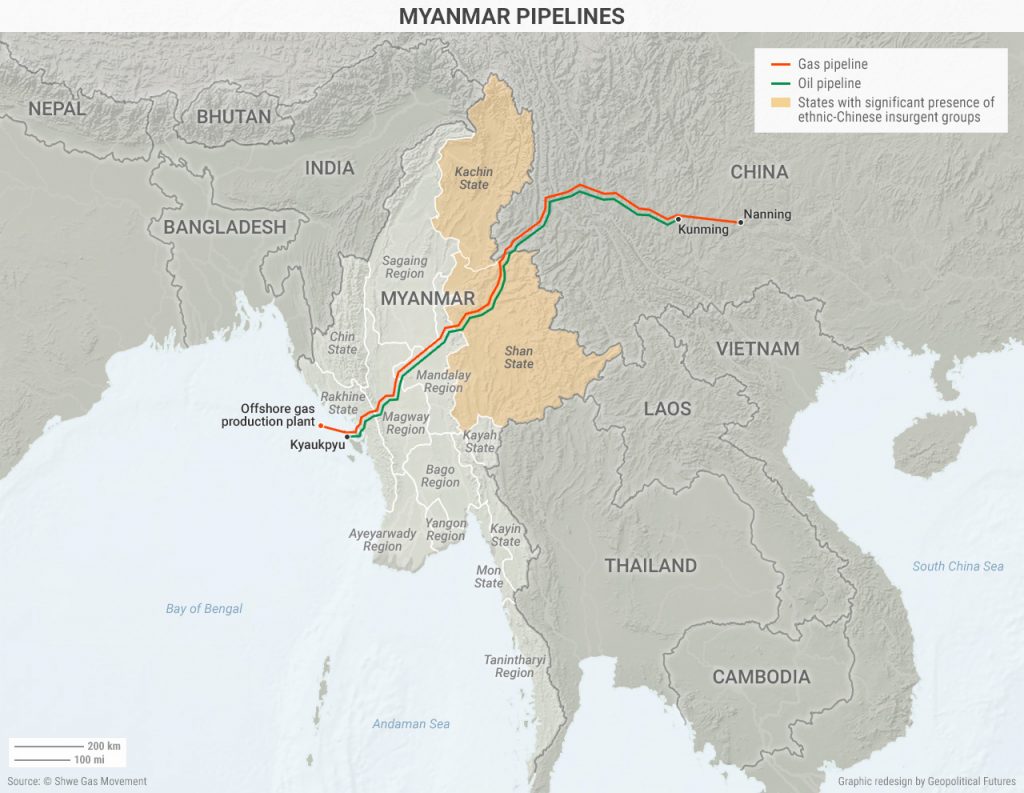

A critical lifeline for China is access to maritime routes. The main and historic ports of China sit along the South and East China seas and are problematic due to their exposure to the Malacca Strait choke point. China can overcome this constraint in multiple ways, including bypassing it altogether with direct land access to the Indian Ocean. China’s approach to securing this overland access to the Indian Ocean is through Myanmar.

Beijing Shifts Its Approach

To achieve this goal, China must have influence over, or be on good terms with, Myanmar’s government. That government is not currently a reliable partner due to its conflict with domestic rebel groups along the Myanmar-China border. These groups are both a blessing and a curse for China. Previously, China funded ethnic-Chinese insurgent groups in north and northeastern Myanmar to escalate conflict that would decrease government control over the states that border China. This gave Beijing both influence among the rebel groups closest to its border and leverage over Myanmar’s government in any peace negotiation.

While China still appears to be funding some of these groups, it is now pushing them to curtail fighting and seek a settlement that favors Beijing. Rebel opposition has created enough of a challenge for Myanmar’s government that China is now beginning to consolidate its gains and establish a pro-Beijing status quo rather than continue its policy of instigating instability to generate additional bargaining chips with Myanmar’s government.

China is now playing a new role as peace-broker. In March, Beijing organized a meeting between the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Myanmar government to mitigate fighting along the Myanmar-China border. At the same meeting, the United Wa State Army (UWSA), which is Myanmar’s largest rebel group with 20,000-30,000 soldiers and has received heavy weapons from Beijing, announced that it wanted to completely do away with the government’s Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement and proposed that China manage a new peace process.

China has also undertaken punitive financial measures to mitigate border-area conflict. In March, the Agricultural Bank of China – one of China’s largest state-owned lenders – suspended an account that the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) – an ethnic-Chinese rebel group based in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone in the northeastern part of Shan State – had been using to crowdfund its activities. This was likely in response to an attack the MNDAA launched on Myanmar government forces earlier in the month in Laukkai, Kokang’s capital. The attack killed at least 30 people and sent over 20,000 refugees fleeing from northern Myanmar into China.

Another recent event gives additional insight into China’s pivot to a more peaceful approach. Last week, China began operating a pipeline that transports crude oil from Myanmar’s Made Island Oil Terminal in the west to PetroChina’s Kunming refinery in China’s Yunnan province, bypassing the Malacca Strait entirely. This pipeline runs through regions that sit on the Chinese border containing active ethnic-Chinese insurgencies. Disruption in these regions no longer serves China’s interests since the breakout of conflict or social unrest could threaten the pipeline’s operations. According to a source who spoke to the South China Morning Post and was familiar with the Southeast Asia Gas Pipeline Company’s activity, protests contributed to delays in the pipeline’s completion.

Playing Both Sides

Despite supporting Myanmar’s military junta for decades, China has also provided military aid to ethnic Chinese rebel groups, most notably the UWSA. While the UWSA has maintained a cease-fire with the government for years, it is believed to have continued providing aid to other active insurgent groups. This dual approach of overt support for Myanmar’s government coupled with covert support for the rebel groups has let China engage in diplomacy with Myanmar that implicitly carries the threat of violence. China has used its clout among these groups to exert leverage over the government, which they believe to be increasingly open to Western influence since the government began implementing reforms in 2011. Those reforms saw a loosening of the military junta’s grip on the government.

China’s moves to broker a peace deal with the KIA and cut funding to the MNDAA are indications that it is implementing a new approach that focuses on establishing a peaceful border with states in Myanmar where rebel groups can establish a degree of autonomy. This strategy is made possible by the challenging terrain in Myanmar’s northeastern states that makes it difficult for the government to establish and maintain effective control.

The Myanmar Armed Forces, known as the “Tatmadaw,” have difficulty providing supplies to troops in the northeastern Kachin and Shan states. Shan State, for example, has only one airport and two major roads. Laukkai, where the March battle took place between the Tatmadaw and the MNDAA, has no nearby airfield, which means supply lines must be maintained solely by helicopters and the single main road from Lashio. This lets rebel groups maintain instability in these mountainous northeastern regions as they can launch offensives at times of their choosing that force the Tatmadaw to respond and keep it reacting to insurgents’ initiatives.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, right, shakes hands with Myanmar’s President Htin Kyaw after a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of People on April 10, 2017 in Beijing, China. Yohei Kanasashi/Pool/Getty Images

While the Tatmadaw has over 300,000 soldiers, combat-capable field units that can respond rapidly to these offensives (such as the Tatmadaw’s “fire brigade”) are stretched thin and have suffered the majority of casualties in confrontations with rebels. That takes a toll on troop morale. By effectively minimizing the Myanmar government’s control over these regions and providing arms to insurgent groups within them, Beijing can exercise greater long-term leverage over Naypyidaw and pressure the government without having to encourage new rounds of violence.

China’s interests in Myanmar have not changed: It needs to find ways around the Malacca Strait, which requires accessing the Indian Ocean by land. What has changed, however, is China’s approach to achieving these goals. China has effectively prevented the Myanmar government from establishing complete control of its northeastern states, and as infrastructure comes online that delivers critical resources to China while avoiding the Malacca Strait, encouraging open conflict that would both threaten these deliveries and risk protracted retaliation by the Tatmadaw no longer serves its interests. While China will continue to wield the implicit threat of rebel-led attacks, it will seek a peaceful resolution with the Myanmar government that allows it to build infrastructure suited to its needs and on favorable terms. However, it is the very presence of this tacit threat that will give Beijing the upper hand in any negotiations with Naypyidaw – even if done under the guise of brokering peace.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East