By Jacob L. Shapiro

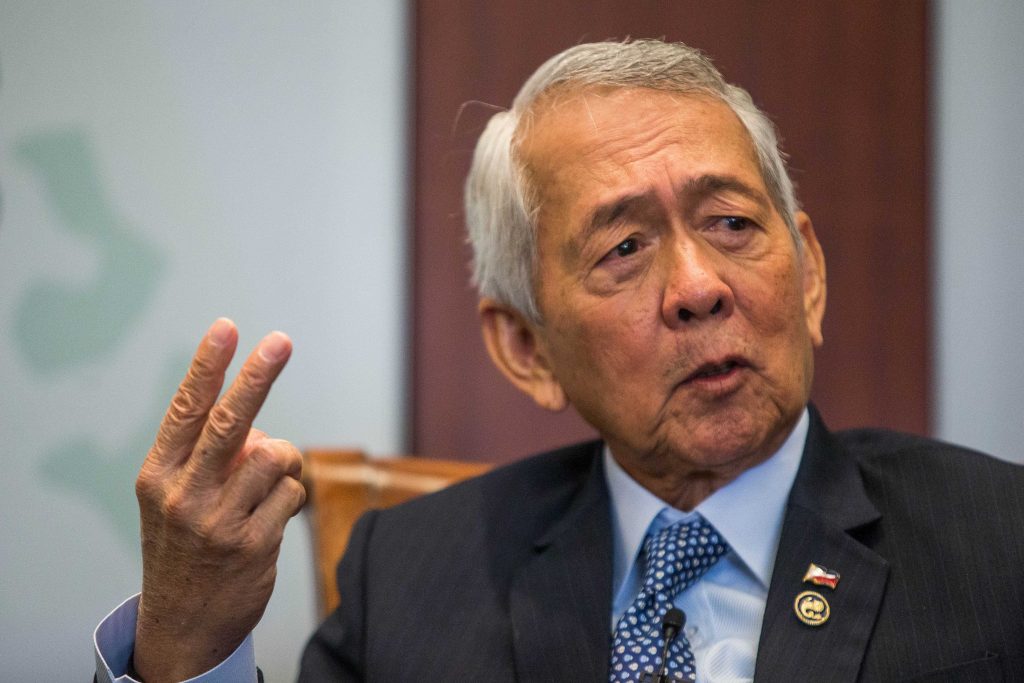

The Philippines Commission on Appointments (CA) rejected the reappointment of Philippines Foreign Secretary Perfecto Yasay Jr. on March 8. This is the same Philippine official who made waves three weeks ago when, after a meeting of ASEAN foreign ministers, he publicly criticized China’s moves in the South China Sea. At the time, China was highly critical of Yasay’s comments, with a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman calling them “baffling and regrettable.” The spokesman urged Yasay to follow the path of relations that Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and Chinese President Xi Jinping had outlined during Duterte’s October visit to Beijing. Yasay now finds himself without a job.

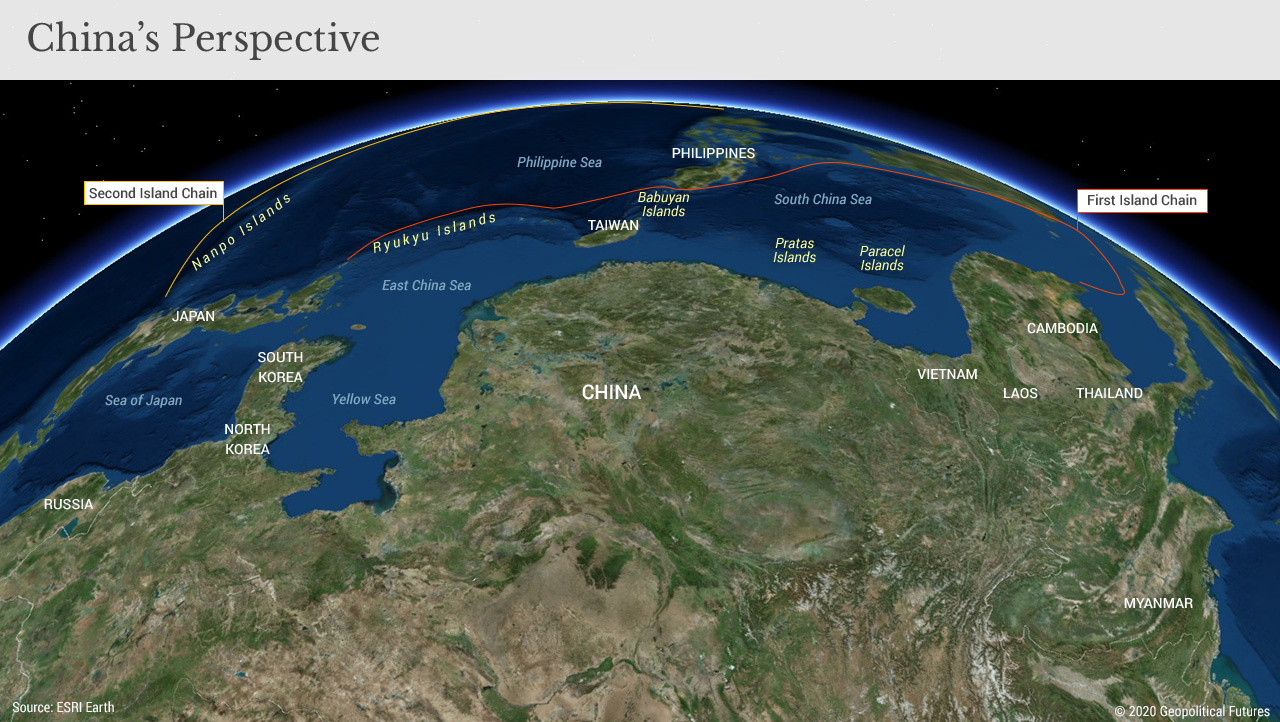

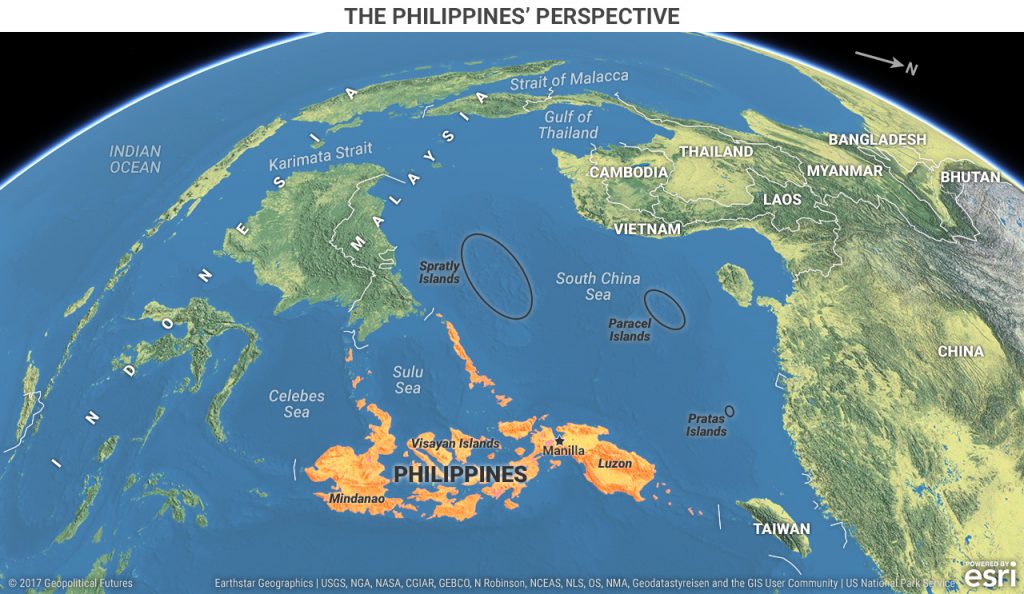

This is the latest episode of an issue that is not expected to disappear over the next few years. China is too militarily weak and economically vulnerable to engage in fighting in its near abroad with the United States and its allies Japan and South Korea. China’s best strategic option is to change the balance of power in the Pacific or in Southeast Asia, either by developing closer relationships with key countries there or destabilizing their domestic politics. Two countries China is focusing on are Myanmar and the Philippines. Earlier this week, Chinese-backed rebels in Myanmar resumed a new round of attacks in the country, frustrating Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s peace initiatives. Yasay’s rejection comes only a few days after that.

Reading Chinese influence in the rebuff of Yasay must begin with a caveat: It could have more to do with domestic Philippine political issues than with China’s influence. The Commission on Appointments is responsible for approving all heads of executive departments, ambassadors, armed forces officers and a range of other positions. The confirmation process itself is often inefficient and serpentine. It is not uncommon for the CA to take years to confirm Cabinet members. In 2014, for example, three Cabinet-level officials were confirmed after already having served four years in their positions. What is unusual in Yasay’s case is that the CA quickly and decisively moved to reject his reappointment.

Former Philippine Foreign Secretary Perfecto Yasay Jr. speaks at a forum at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 15, 2016. ZACH GIBSON/AFP/Getty Images

Yasay also was caught red-handed in a lie. The former foreign secretary said he had never held U.S. citizenship or a U.S. passport, but he was granted U.S. citizenship in 1986, had held a U.S. passport, and only renounced his U.S. citizenship last June – two days after he was nominated for the post. The 15-person commission unanimously decided to reject Yasay, and Duterte already has nominated a new official to replace him.

There are too many coincidences to conclude the analysis here. First, on March 6, the Philippines and China revived the Joint Commission on Economic and Trade Cooperation, which had not met for five years due to territorial disputes between the two countries. On March 7, the day before Yasay’s rebuff, Chinese and Philippine trade officials announced China intended to finance at least three infrastructure projects in the Philippines worth $3.4 billion. China also reportedly agreed during the commission’s meeting to purchase $1 billion of Philippine agricultural products this year. Yasay’s comments at ASEAN last month resulted in the cancellation of a visit by China’s commerce minister to Manila to sign economic agreements. Injecting new life into those deals the day before Yasay’s downfall was fortuitous timing.

The issue goes beyond the announcement of a few economic promises (the word deal should be reserved for when the checks actually clear). Duterte has been relatively quiet on the issue of China-Philippines relations in recent months. If anything, his attitude toward China has been ambiguous at best. Duterte made no prominent statements after the ASEAN incident, which is strange for a leader with a demonstrated penchant for controversial sound bites. He also hosted Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in January, the first foreign leader to visit him in Manila. The two sides agreed to a number of aid and investment deals. Duterte broke his silence on March 8 during a speech at the 10th Philippine Councilors League National Congress, where he profusely thanked China “for loving us [the Philippines] and giving us enough leeway to survive the rigors of economic life on this planet.”

On the same day, China made a point of announcing that the first draft of a Sino-ASEAN code of conduct had been completed after seven years of abortive negotiations. The importance of this is not the draft itself, details of which have not yet been released. The draft likely contains little that will change the region’s balance of power. Many more drafts will be completed and years of wrangling will ensue before anything is actually signed, let alone put into practice in the South China Sea. What is important is that China is touting the diplomatic role it has played in writing this draft. It is doing so while the Philippines holds the presidency of ASEAN. And China is trumpeting this diplomatic success in the arena where Yasay publicly held China to the fire just a few weeks ago. For good measure, China’s foreign minister also took the opportunity to fire a diplomatic salvo at the United States over U.S. freedom of navigation operations in “contested waters.”

It is possible that all of this is just a coincidence, but coincidences are rare in geopolitics. Yasay was considered close to Duterte, and the two were roommates in law school. That Duterte was unable or unwilling to save Yasay might be evidence of an internal power struggle in the Philippines. For example, the Philippine defense minister has been consistently skeptical of Duterte’s desire to move closer to China and made comments to that effect on March 9. But the same day that Yasay’s reappointment was rejected, Duterte made public remarks about China that effectively repudiated Yasay’s position at the ASEAN meeting. It is reasonable to conclude that Duterte either lost trust in his confidant, did not sign off on Yasay’s comments at ASEAN, or had his hand forced by the revelation of Yasay’s lie. The public coordination on announcing new economic deals between the Philippines and China and China’s opportunistic announcement of its diplomatic success at ASEAN also suggest that China was ready to capitalize on Yasay’s fall from grace.

Yasay’s ouster does not change the region’s balance of power. There are still limits to the Philippines’ ability to drift from the U.S., and to China’s capability of pulling the Philippines into its orbit. Thinking about such a large shift in the balance of power may be premature, anyway. China would love to flip the Philippines into a potential ally. But short of that, provoking domestic instability to disrupt the U.S.-Philippine relationship is a decent consolation prize from Beijing’s point of view. The reality check is this: Potential war in the South China Sea and the blowing winds of a trade war are sideshows. The main arena where China can make moves is in the domestic affairs of places like the Philippines. That makes a foreign secretary candidate’s rejection in the Philippines a matter of geopolitical importance.