By Jacob L. Shapiro

If you go to the World Bank’s country overview page for China, you will find a striking comment in the first paragraph: “Since initiating market reforms in 1978, China…has lifted more than 800 million people out of poverty.” Speaking at the G-20 summit in Hangzhou at the beginning of this month, Chinese President Xi Jinping said that China has lifted “more than 700 million people out of poverty” and improved the living standards for 1.3 billion people overall. So China and the World Bank agree, give or take a hundred million people.

Xi also noted in his remarks that this success is unprecedented in human history. He happens to be correct about that – no country has ever made the sort of developmental leaps that China has made in the last 38 years since opening up its economy, or in the last 67 years since the Communist Party came to power. The problem is that the World Bank’s definition of poverty in this case is extremely narrow, and the 800 million figure obscures, rather than reveals, that poverty is still a significant problem in China and one of the most important drivers of our forecast for the country.

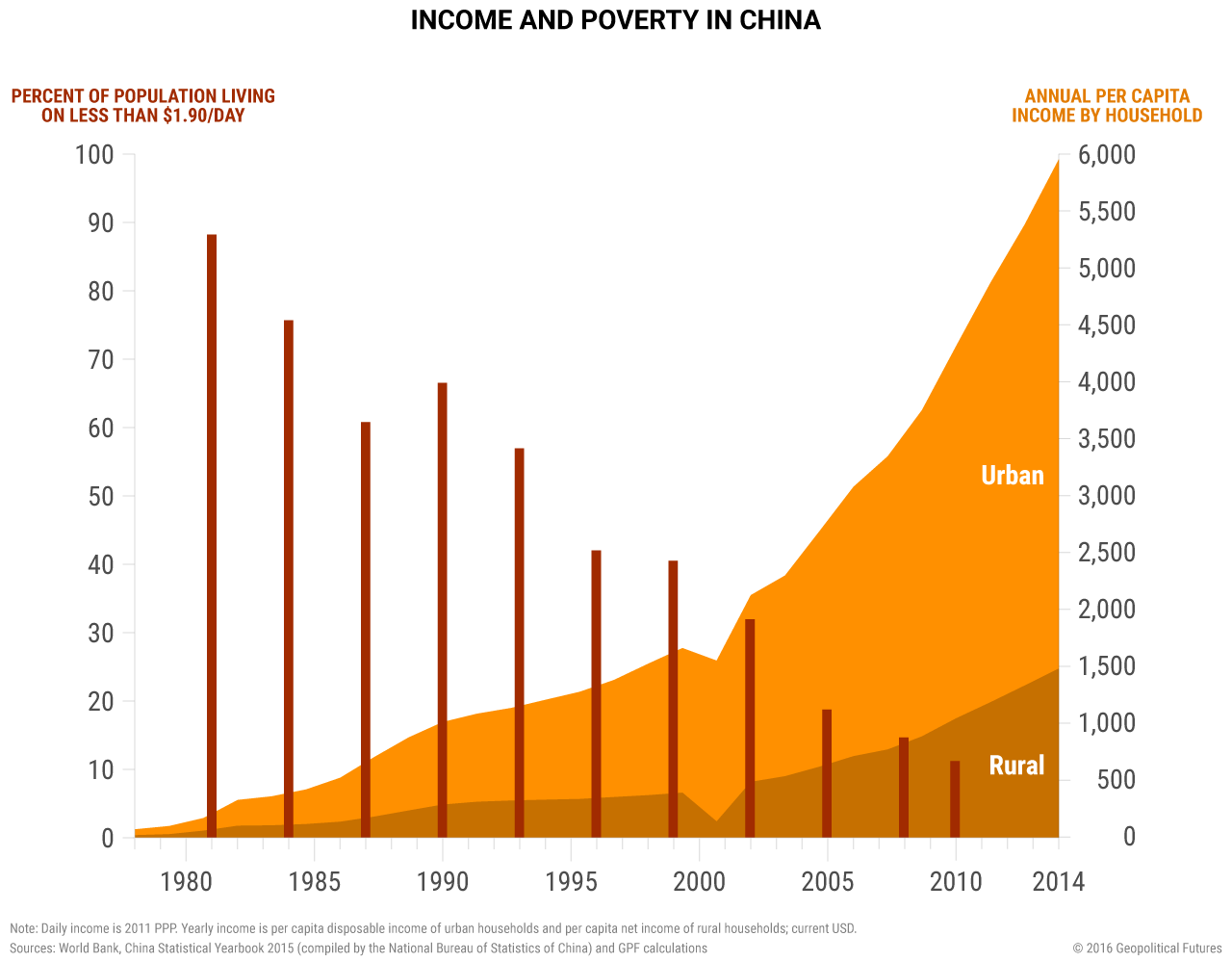

The World Bank began tracking poverty in China in 1981. In that year, 88.3 percent of China’s population lived on less than $1.90 a day (roughly 870 million people). Push the threshold up a little bit and poverty in China was even more striking: 99.1 percent of China’s population lived on less than $3.10 a day (over 980 million people). The last year for which the World Bank has official data is 2010, and the transformation, as you can see in the line graph above, is extraordinary. In 2010, only 11.2 percent (almost 150 million people) lived on less than $1.90 a day. Not shown above is that 27.2 percent (almost 360 million people) lived on less than $3.10 a day.

However, the problem with these data sets should already be clear. If you factor in population growth, you can make the claim that China has lifted 800 million people out of poverty if you define poverty as living on less than $1.90 or $3.10 a day. This doesn’t say anything about how well those lifted out of poverty are doing. A rural household living on $1.91 a day by this standard wouldn’t be counted as suffering from extreme poverty, even though by any objective measure a household earning that much on an annual basis would be cripplingly poor.

Another less obvious problem is in some ways more serious. The average annual per capita disposal income by household in China in 2014 was about 20,071 yuan – about $3,000, or $8.22 a day. On the face of it that seems a somewhat promising figure. It wouldn’t make any of these households rich, or even lower-middle class by American standards, but it would be quite a leap forward from where they started. The average figure, however, is skewed by the huge disparity between urban and rural incomes. Urban households’ per capita income was 29,831 yuan – almost $4,500 a year. Rural households have a per capita income of only 9,892 yuan – about $4 dollars a day.

The rejoinder to this is that far more Chinese citizens work in the cities than in the countryside compared to any other period in Chinese history. And this is true, to an extent. One of the most remarkable things about China’s transformation is how it has urbanized. When the Communists came to power, 80 percent of the people lived in the countryside. There was no proletariat in China – the revolution was carried out by a massive agricultural peasant class. In 1978, only about 23 percent of people employed in China were urban workers – the country was still predominantly rural. As of 2014, over half of China’s roughly 770 million employed workers were urban workers. The problem is that the other half – almost 380 million people – are employed in rural areas. The urban households aren’t exactly raking it in, but the rural households have not progressed far enough beyond the World Bank’s arbitrary $3.10 to say they have escaped much of anything, and certainly not poverty.

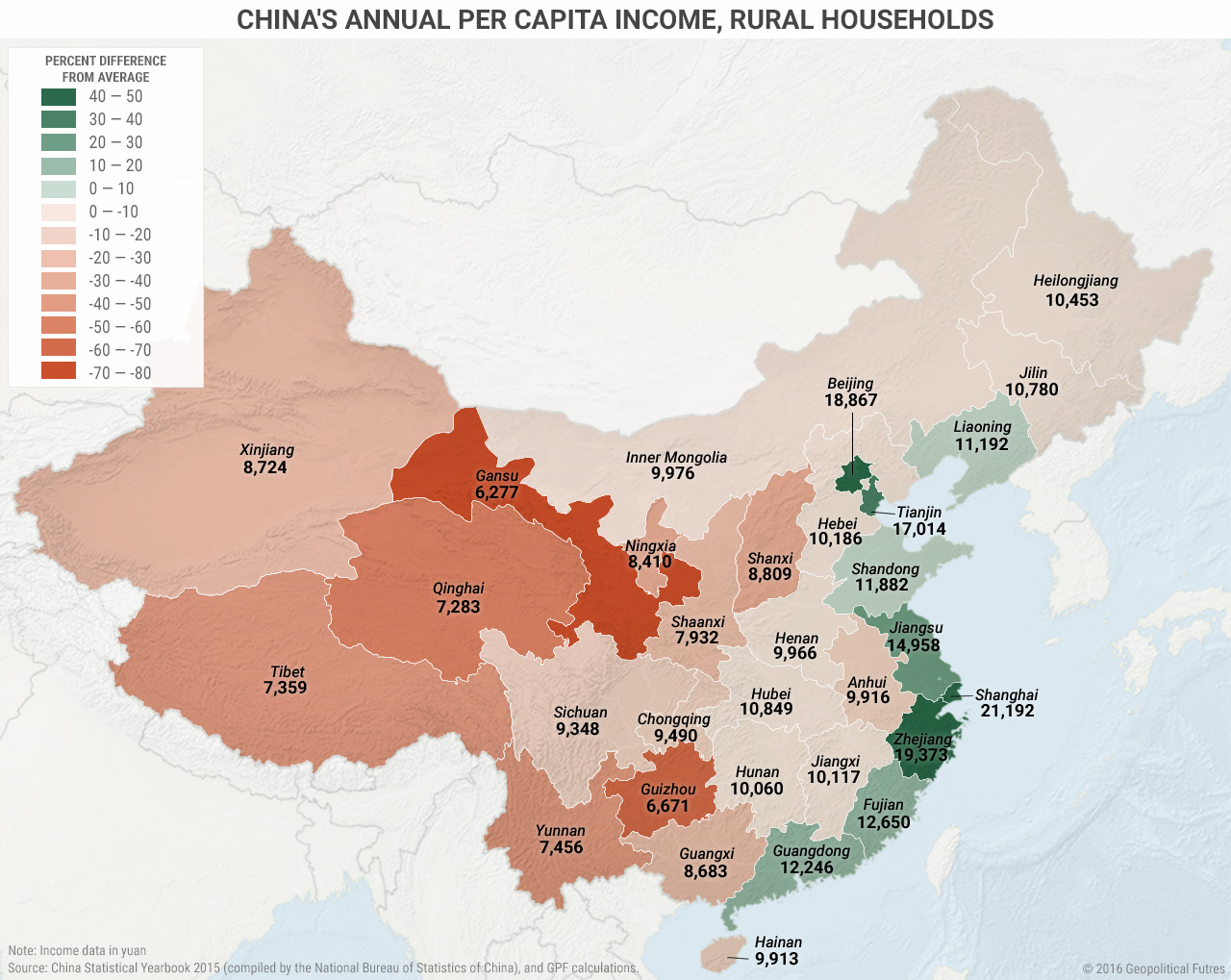

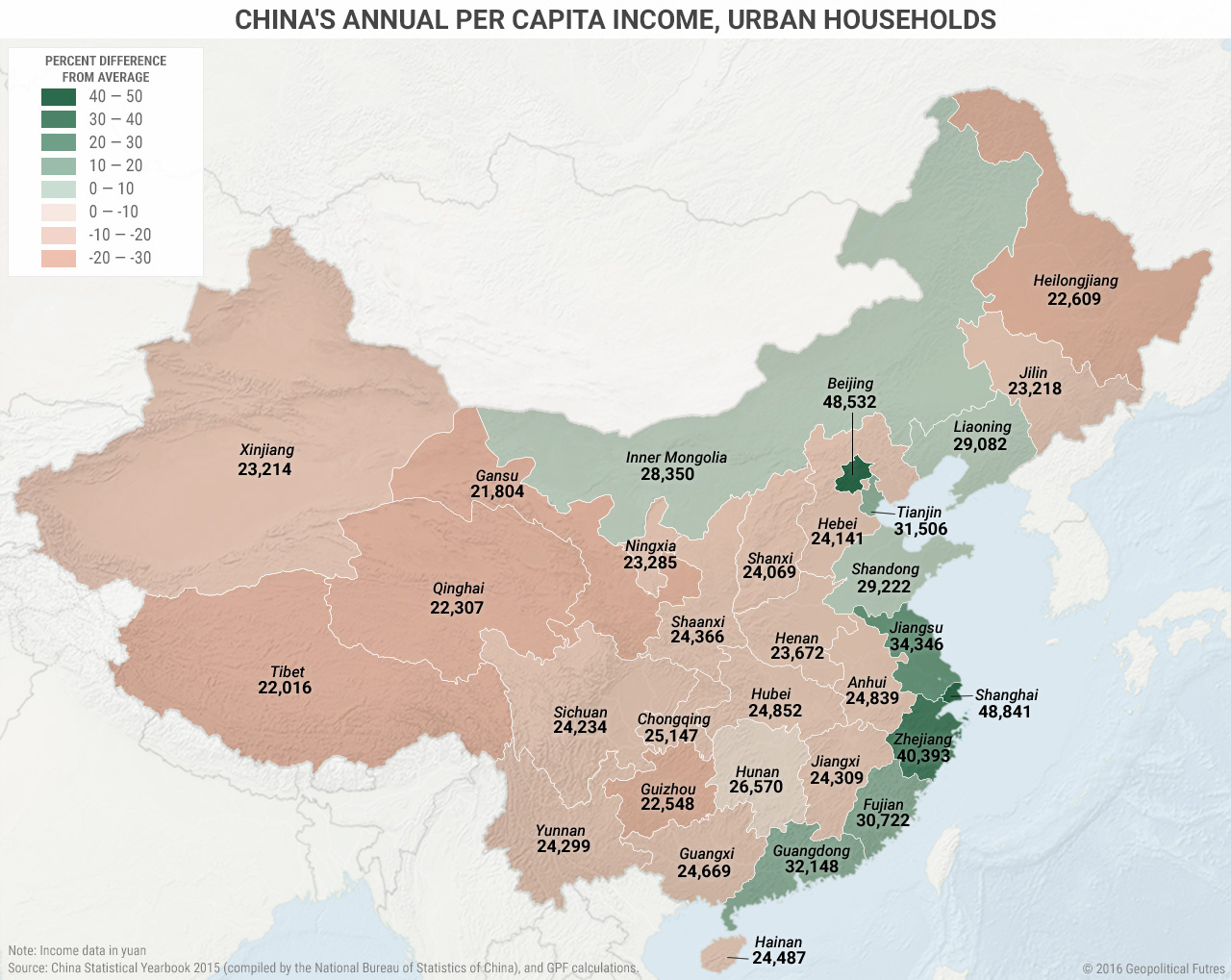

There is another divide that also skews the data upwards: the division between the coastal and interior provinces.

The above maps strikingly show how relevant this dichotomy remains in Chinese society today. Urban households in coastal cities like Beijing or Shanghai are faring quite well. An urban household’s per capita disposable income in Beijing is 48,531 yuan and in Shanghai it is 48,841 yuan. McKinsey & Company released a report in 2013 that predicted that 75 percent of China’s urban consumers would be middle class by 2022 – a whopping 270 million people. That’s a middle class almost the size of the entire population of the United States. McKinsey expects these urban households in the most successful Chinese cities to make between 60,000 and 229,000 yuan a year within the next eight years.

The problem is that the advancement is not being enjoyed evenly. Even the urban households in many of the interior Chinese provinces are earning far less than the per capita average. Meanwhile, cities like Beijing and Shanghai are doing over 43 percent better than the mean, and urban households in coastal provinces like Zhejiang or Guangdong are also doing extremely well. The contrast is even starker when you look at the map of urban household income beside a map of per capita disposable income by rural household. The rural workers in the coastal provinces are doing far better than their peers in the interior provinces, many of whose per capita incomes per household remain dangerously close to the World Bank’s poverty cut-off.

None of these facts should detract from recognizing that the era of growth and transformation ushered in by Deng Xiaoping has been nothing short of extraordinary. Despite the challenges outlined above, China is the world’s second largest economy, and even minor fluctuations in China can send ripples throughout the global economy. Both urban and rural households, on the coast and in the interior, have seen their incomes steadily increase. But it hasn’t been enough, and China is running out of steam. The high growth rates it depended on to drive its industrialization and urbanization have begun to slow down, and those growth rates aren’t going to go back up. By the World Bank’s standards, China has lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens out of poverty. There are hundreds of millions, perhaps even half a billion more, who have not been lifted out of poverty, who look around and see that they have not participated in China’s rise and that their prospects for joining look more like the central government telling them to tighten their belts for yet another generation.

For decades now, generations of Chinese poor have done just that. The question is whether there are limits to their patience. It is this question that drives many of the items on our watch lists, like yesterday’s reports that 45 National People’s Congress fat cats were expelled for corruption and that a violent crackdown was under way on protests against central government authority in Wukan. Or the news on Monday that the government had to censor information after Chinese social media became enraged about a People’s Armed Police Force officer using his position to travel first class. The Chinese economy has accomplished a great many things, but solving poverty is not one of them. It looms behind every step Beijing takes, no matter what the World Bank or Xi say on the matter.