Originally produced on Feb. 6, 2017 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

George Friedman and Jacob L. Shapiro

Newly minted Secretary of Defense James Mattis wrapped up his first international trip earlier this month. According to a Defense Department press release about his visit to South Korea and Japan, Mattis’s purpose was to “listen to the concerns of South Korean and Japanese leaders.” The two countries are crucial US allies in Asia, and both face serious threats in their near abroad.

Discussing security threats, however, wasn’t the primary purpose of Mattis’ visit. The purpose was to reassure both countries that the administration of President Donald Trump will not abandon the US alliance structure in the Pacific.

In light of Mattis’s visit, we thought it might be useful to examine current US military and investment positions in the Asia-Pacific region.

US Military Commitments in Asia-Pacific

The United States used containment as its primary strategy in blocking the Soviet Union. Looking at the map above, we can see that the US is following a similar strategy with China. US military assets stationed in Asia-Pacific countries have two purposes. First, they ensure US naval power projection in the Pacific Ocean. Second, and by extension, they help contain Chinese ambitions.

Besides Guam (which is US territory), the US has no sovereign soil in the Western Pacific Ocean. The US must therefore have good relationships with strategically located countries in the Pacific where it can base ships and soldiers. Japan, South Korea, and Australia are the most important US allies in the region, but the US also maintains varying degrees of cooperation with countries like the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore.

The Philippines is a key part of this strategy. But it is also being courted by China. Geopolitical Futures is bearish on China’s long-term (even medium-term) future. Currently, however, China is the second-largest economy in the world. It is pouring money into its military development and trying to attract cooperation from other countries. The Philippines is the prettiest girl at the dance right now—Manila has Washington, Beijing, Tokyo, and others chasing it around with promises of investment and protection in return for security guarantees.

The Mutual Defense Treaty between the US and Philippines remains in place, but the two sides only recently agreed on which Philippine bases the US can use. The US still hasn’t been given permission to return to the much-coveted naval base at Subic Bay. The Philippine president is also full of anti-US rhetoric these days.

The US wants naval control of the oceans. It has a strong navy, but a navy by itself isn’t enough. Containing China is another major part of its Pacific strategy. Even if China could be contained by means other than US power, the US would still want Pacific partners to help project its naval power.

Beneath all the noise is the simple fact that the US maintains an impressive military presence in the Pacific. Mattis will remind US allies how important they are to US interests and that US intentions can be measured in commitments, not headlines.

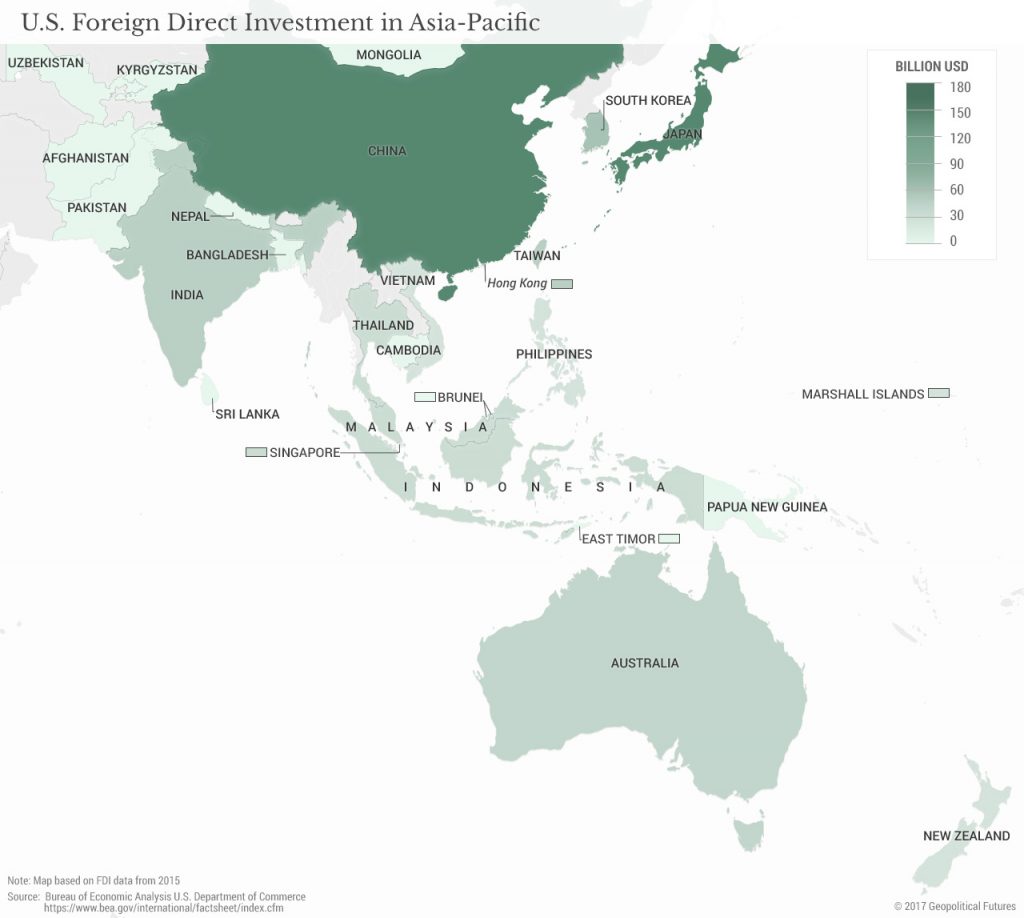

US FDI in Asia-Pacific

In addition to its military strategy, the US is employing an economic strategy. It wants countries to see the economic benefits of cooperating with the US. The United States is the largest economy in the world. It has used this economic power very effectively in the past.

The first thing to note from the map above is that the largest destination for US foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Asia-Pacific region is not an American ally… but China. China’s economy is in the midst of a huge transition. The US-Chinese economic relationship is important to both sides, but particularly for China. The US is China’s largest export market. This happened in part because US companies could profit by moving production to China. Now, Beijing needs to move up the value chain by attracting foreign investment and technology (of which the US is a major source). If China seriously challenges the US, it risks these economic benefits.

The next five largest beneficiaries of US FDI in the region are crucial American allies and partners. Japan, South Korea, and Australia are at the top of the list. Singapore, located on the strategically important Strait of Malacca, is next. The military containment strategy displayed by the first map focuses mainly on blocking Chinese access to the Pacific. In contrast, this map of US FDI distribution shows a strategy not of containment but of widespread US economic influence across Asia-Pacific.

It should also be noted that some US FDI is directed to small countries, such as the Marshall Islands. The amount of FDI is lower because these are smaller economies, but the investments are arguably more important for the economic development of those countries. Being a US ally, or even a US partner, means access to US investment. The price of being a US ally can be high, but it also comes with key benefits.

Mattis’s Trip

These two maps are snapshots of US power. They are also snapshots of US needs. The US imperative is to maintain its dominance of the world’s oceans. Ships need ports. Planes need bases. For these basic necessities, the US must have good relationships with strategically located countries in the Pacific. These countries, in turn, rely on the US for protection and for preservation of the status quo.

The Trump administration wants more from its allies… not less. Mattis’s job will be to communicate the reliability of US security guarantees, and also to remind these countries that the relationships exist because of shared interests. The US asking more of these countries does not mean US presence will decrease. It means admitting US presence will not solve all their problems.