By Xander Snyder

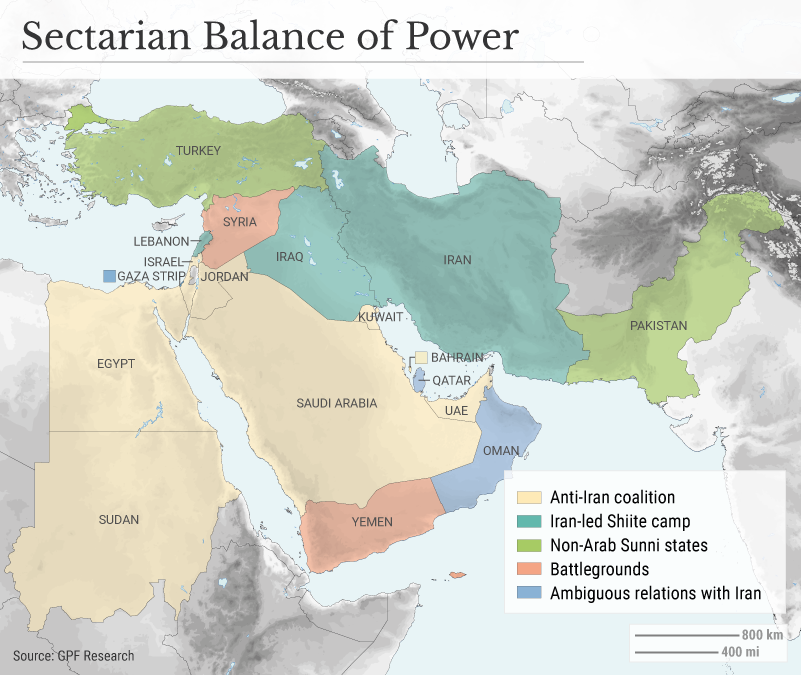

From a humanitarian perspective, the Yemeni civil war is a tragedy that has cost thousands of lives. From a geopolitical perspective, it is yet another place where two of the Middle East’s main powers, Saudi Arabia and Iran, are competing for control.

Over the past few days, the crisis seems to have taken another turn. Former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh turned on his coalition partners, the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels, after clashes in the capital, Sanaa, which the coalition had taken from the Saudi-backed government. Then, on Dec. 4, Saleh was killed amid fighting between his loyalists and his former supporters. The Houthis are now being tested, and the outcome will greatly influence the course of the war in Yemen.

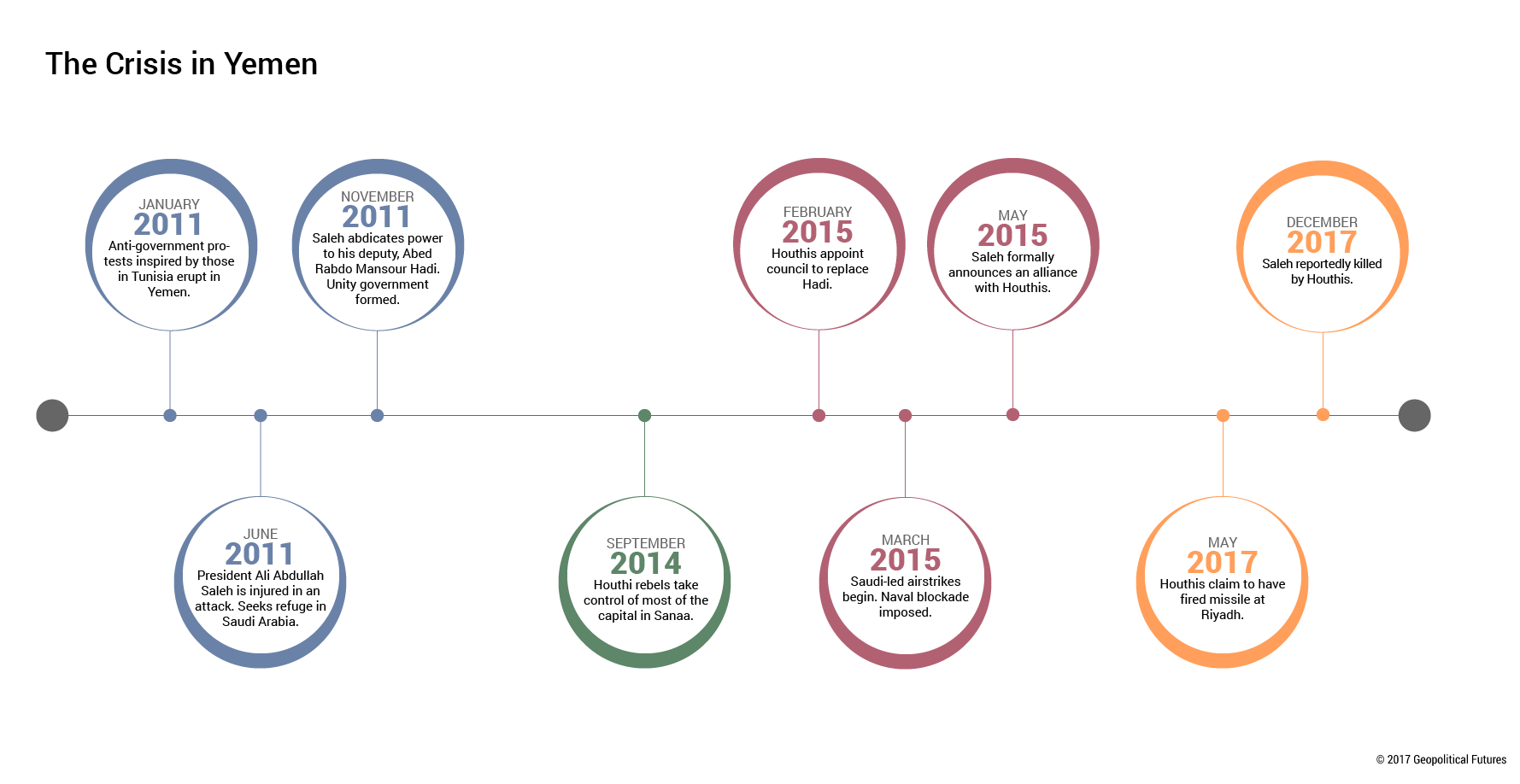

How We Got Here

The most recent phase of the conflict in Yemen started in 2014 and involves two primary coalitions. On the one side is the now-defunct Saleh-Houthi coalition. On the other side is an alliance between Saudi Arabia and the government of President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi, who came to power after Saleh abdicated in 2011 in the wake of the Arab Spring uprisings. Hadi is currently in exile in Riyadh, which intervened in the war to prevent the Iranian-backed coalition from taking over the country.

Saleh ruled Yemen for over 30 years and had been a firm supporter of Saudi Arabia. Why, then, did he join in a coalition with a group backed by Iran, Saudi Arabia’s regional rival? He was forced from office by the uprising, and his former patron – Saudi Arabia – was unable to prevent it. Following an assassination attempt, he realized that Saudi Arabia couldn’t assure his safety and that working with the Houthis was the only way he could regain power. When Saleh joined forces with the Houthis, they quickly took over Sanaa in 2014. Saudi Arabia intervened on behalf of the internationally recognized government led by Hadi to prevent the newly formed Houthi-Saleh coalition from toppling the government and turning the country into an Iranian proxy.

But last week, Saleh broke his alliance with the Houthis and stated publicly on Dec. 2 that he’d be open to discussions with the Saudis. Though this wasn’t wholly unexpected given Saleh’s past ties to Saudi Arabia, abandoning the rebel coalition would have left the Houthis isolated. Just days later, the Houthis assassinated Saleh, calling into question whatever deal with Saudi leaders that Saleh had in mind.

In Sanaa, the former Houthi-Saleh coalition partners began fighting. Hadi, recognizing an opportunity, ordered his forces on Dec. 4 to move on the capital while the Houthis were preoccupied. Since Saleh was instrumental in enabling the Houthis to so quickly take Sanaa from the government, the collapse of the coalition and Saleh’s subsequent death has created division within the former rebel coalition, and Hadi hopes to exploit it before the Houthis can recover.

Saleh was not just a skilled political operator – he was also a top general in Yemen’s military. He undoubtedly traveled with a security entourage. The Houthis’ ability to quickly locate him, penetrate his security and kill him is a sign that the Houthis – and therefore the Iranians – have established a firm grip on power, with robust intelligence capabilities, in part of the country. But with the rebel coalition now divided, Iran’s proxy faces a serious threat to its hold over Sanaa and, therefore, a major part of Yemen.

Iran’s Response

In response to the turmoil, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said Yemen’s domestic problems “should be resolved through dialogue to prevent foreign enemies from abusing the Yemeni nation.” There are two ways to interpret Rouhani’s comment. First, he may be concerned that the Houthis’ – and therefore Iran’s – position in Yemen has become seriously challenged, so much so that he might be willing to engage in dialogue. The second interpretation is that Rouhani simply wants to begin negotiations but intends to keep the fighting going to gain as much leverage in the negotiations as possible. Ongoing fighting and negotiations would enable Iran to pursue its objectives in Yemen in the diplomatic and military spheres at the same time.

Houthi rebel fighters are seen riding an armored vehicle outside the residence of former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh in Sanaa on Dec. 4, 2017. MOHAMMED HUWAIS/AFP/Getty Images

Iran’s goals in Yemen are easier to achieve than Saudi Arabia’s. Saudi Arabia wants to rid the Arabian Peninsula of Iranian influence, which requires eliminating Iranian proxies in Yemen, a much harder task than simply keeping the war raging to force Saudi Arabia to divert its resources and manpower to Yemen. An ideal outcome for Iran would be a resolution that incorporates the Houthis into some form of legitimized government, similar to Hezbollah’s arrangement in Lebanon. Failing that, Iran would be happy to keep Saudi Arabia distracted by fanning the flames of war on its southern border.

With the opposition now divided, two critical questions remain regarding Iran’s position in Yemen: Are Saleh’s forces strong enough to continue to pose a threat to the Houthis in Sanaa? And are Hadi’s forces powerful enough to retake the capital? Estimates of both parties’ troop levels are scarce, and some are more reliable than others. In 2011, Houthi leader Abdul-Malek al-Houthi claimed that the group had 100,000 fighters. But estimates from the International Institute for Strategic Studies are significantly lower. In 2017, IISS estimated that there were roughly 20,000 insurgents in Yemen, including the Houthis and the Yemeni Republican Guard, which was controlled by Saleh loyalists. (It is unclear whether other forces loyal to Saleh were included in these figures.) IISS estimated the size of Yemen’s army, including its militia, at between 10,000 and 20,000. Saudi Arabia provides air support and military advisers for the Yemeni army. But the Houthis also showed a degree of sophistication when they fired a ballistic missile, almost certainly made by Iran, at Riyadh last month. That the rebel coalition and the army are so similar in size explains why Saleh’s changing sides could alter the balance between the two sides.

If Hadi and his coalition are able to retake Sanaa, it would be a sign that the collapse of the Saleh-Houthi alliance has seriously weakened Iran’s position in Yemen. However, it would by no means portend an end to the war. Iran does not need to hold Sanaa to keep Saudi Arabia tied down in Yemen; it just needs to keep the war going. On the other hand, if the Houthis are able to eliminate Saleh’s loyalists from Sanaa and repel an attack by Hadi’s forces, it would be a clear sign that Iran’s power in Yemen has cemented, and that Saudi Arabia will not be able to easily uproot it.