By Antonia Colibasanu

Located on the western edge of the Caspian Sea, with Russia to its north and Iran to its south, Azerbaijan is a geopolitically strategic country. It is also a country facing serious economic problems, and if these problems trigger instability and weaken the government’s control, Azerbaijan will become vulnerable to external powers like Russia and Iran. Thus, Azerbaijan’s economic problems and its potential weakening as a state could have consequences beyond its borders, for the Caucasus region and even for the United States.

Economic Challenges

One of the most recent examples of the country’s economic troubles concerns the International Bank of Azerbaijan, which filed for bankruptcy May 11 after failing the previous day to make a scheduled payment on a $100 million loan to a creditor. The IBA also announced that it has suspended all foreign debt payments and will present its voluntary restructuring plan on May 23. The bank is the most important lender in Azerbaijan, controlling more than a third of the country’s banking assets, and it has previously been rescued by the state.

The IBA’s problems started as Azerbaijan’s economy weakened. In early 2015, the country’s national currency, the manat, depreciated by 35 percent after a severe drop in oil prices. As a result, the cost of servicing the bank’s external debt increased by 20 percent, since it had been borrowing in foreign currency and lending domestically in manats. Further currency depreciations and defaults on loans resulted in an increase in the rate of nonperforming loans, which reached as high as 80 percent of the bank’s total assets in just three months.

Azerbaijan’s opposition supporters hold national flags during a rally against the devaluation of the national currency, the manat, in central Baku on March 15, 2015. TOFIK BABAYEV/AFP/Getty Images

In March 2015, the Azerbaijani government took over the IBA, announcing that it would inject about $355 million to recapitalize the bank and spend about $2 billion to absorb bad assets. But in November 2016, Fitch Ratings downgraded the bank’s viability rating because it found that the government had actually injected about $6 billion into the bank, three times more than expected. It was also discovered that prominent businessmen in Baku were taking out loans from IBA that they had no way of repaying. This situation was not unique to IBA, however, as most banks in Azerbaijan are guilty of giving out bad loans and borrowing in foreign currency.

With low oil prices and a depreciating currency continuing to drag down the economy in 2016, Azerbaijan revoked the licenses of a dozen smaller banks that had insufficient capital. At the time, the government seemed to have a handle on the country’s banking problems. Officials even started discussing privatizing IBA toward the end of 2016 – it appeared that the bank was safe.

The recent news about IBA’s default, however, suggests that the bank’s problems are more severe than they appeared, and the government seems to have poorly managed the issues in the banking sector. That Baku couldn’t spend $100 million to keep the bank from defaulting led to rumors that its sovereign wealth fund had less liquidity than was previously thought. This is an important point because Baku is using the fund, the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan, to prevent the country’s currency from depreciating further. To avoid a run on the manat and keep inflation down, the government used SOFAZ funds to help repay foreign debt guaranteed by the state and provide liquidity to banks.

Official reports say that since 2015, SOFAZ’s total value has dropped by only $4 billion, from $37.1 billion to $33.1 billion. But further information about the fund’s financial health is hard to come by, and IBA’s problems since 2015 have shown that the information that Baku provides isn’t always reliable. Even government reports on spending of SOFAZ funds since January indicate that Baku has accessed these funds frequently. Since the beginning of 2017, $4 billion was transferred to the central bank to help slow the currency’s depreciation, and $543.4 million was spent during the first two months of the year in currency auctions organized by the central bank. In March, Baku announced that it would transfer $3.5 billion from SOFAZ to the state budget. SOFAZ receives most of the revenue from oil operations and finances the country’s budget accordingly.

Azerbaijan’s Strategic Value

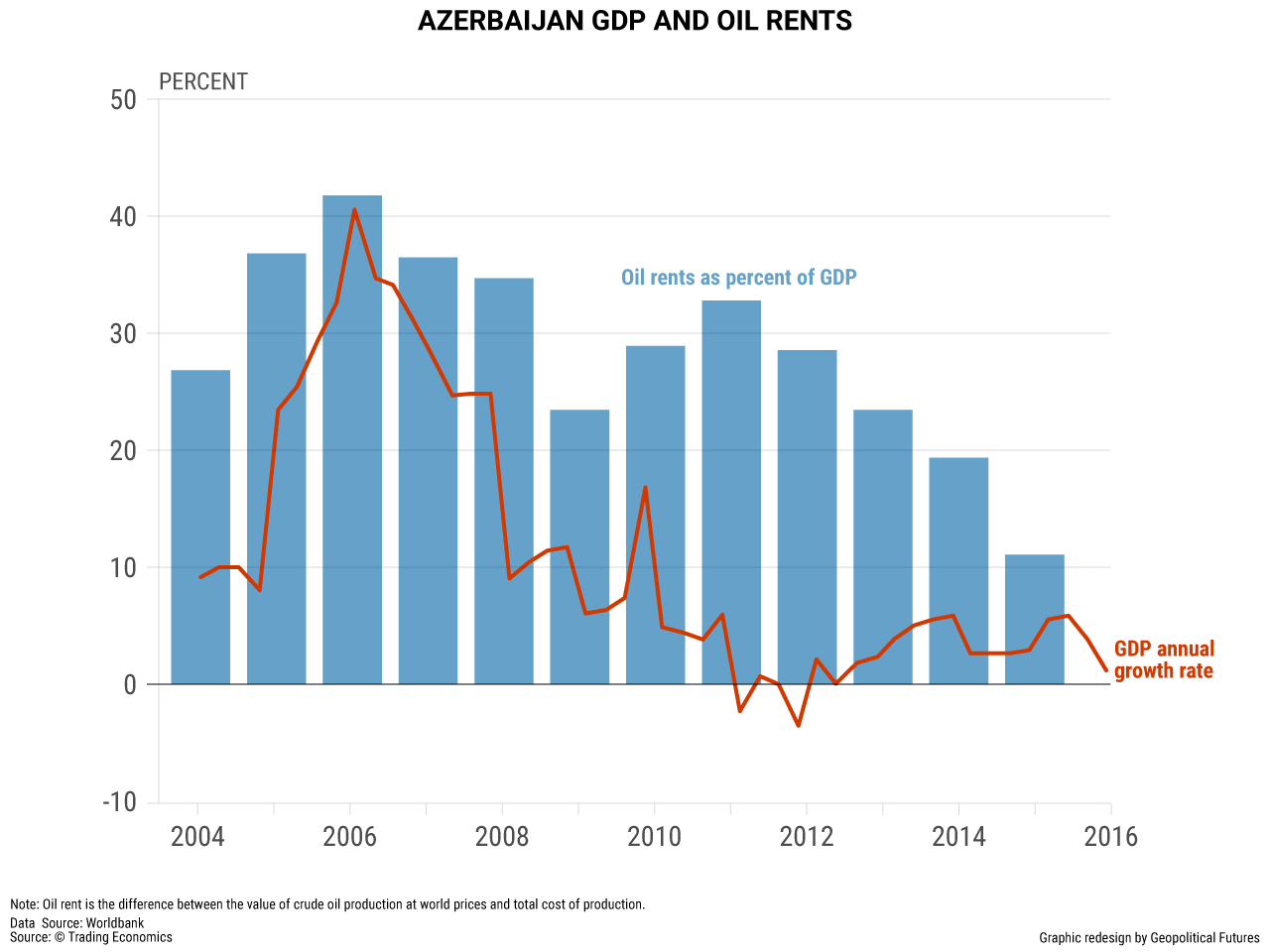

Azerbaijan’s economic development is largely dependent on the oil industry, with the sector accounting for 45 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. But its economy has been hit hard by the slump in oil prices. Roughly 75 percent of the state’s budget revenue comes from energy exports, leaving it in a similar position as other energy exporters like Russia and Saudi Arabia. When oil prices were high, the government was in a secure position. But now, the potential for protests and social unrest is mounting, which creates a dangerous opening that outside powers can exploit. Azerbaijan is especially vulnerable, moreover, because it has powerful neighbors – Russia and Iran – to its north and south. It also has an ongoing conflict with its neighbor to the west, Armenia, over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh and has developed a strategic relationship with Turkey.

Azerbaijan is also strategically important to the United States because it could play a role in the U.S. revival of its Cold War containment strategy toward Russia. The Kremlin has been increasingly assertive since 2008, and now that a pro-Western government has taken office in Kiev, Russia is especially determined not to see any other parts of its buffer zone fall under Western influence. Thus, Russian President Vladimir Putin has been more engaged in the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. He also wants the Russian public’s focus to stay on foreign affairs and external conflicts, rather than on the poor state of the Russian economy.

The U.S. response to Russia’s actions in Europe has been to revive the containment strategy, which now encompasses Eastern European states between the Baltic and the Black seas, with Poland and Romania as the main U.S. allies in this endeavor. For this strategy to be effective, it needs to incorporate the southern Black Sea region and stretch to the Caspian, through the Caucasus region. This extension would include Azerbaijan in the containment line. But Turkey’s cooperation is key to ensuring this strategy can incorporate countries to the east like Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan has cultivated a special relationship with Turkey, which is a NATO member and has strong relations with the United States. But Turkey and the U.S. don’t see eye to eye on everything, and tensions between the two countries have made it impossible for the U.S. containment strategy to push eastward into Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan is also a prime example of the competition between Russia and Turkey for influence in the Caucasus. In the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Armenia is supported by Russia while Azerbaijan is supported by Turkey. But while Azerbaijan has strengthened its military ties with Turkey in the past few years, engaging in more frequent and larger military exercises, it is still largely dependent on Russian arms exports, even though Russia represents a major security challenge considering its conventional military deployment in Armenia.

Iran, on the other hand, has limited influence in Azerbaijan, consisting of investment in the automobile sector and using Shiite Islam to keep conservative elements alive in the country. Since 2015, there have been increasing reports in local media of the government trying to contain pro-Iranian Shiite groups in the south. Baku is concerned that those groups, though still marginal, could pose a threat to its authority. Iran isn’t yet an ascending power in the region, so the Iranian threat is minimal. But Azerbaijan’s fears of growing Iranian influence are real. Azerbaijan was once part of the Persian Empire. In 1813, after the first Russo-Persian war, the Treaty of Gulistan split the ethnic Azeri people in two. The northern Azeri population lived under Russian and Soviet rule until the Soviet Union disintegrated and Azerbaijan became independent. The southern Azeri population lived under Persian rule and is still largely located in Iran, accounting for 5 percent of Iran’s population.

Where Azerbaijan Goes From Here

There are no easy solutions for Azerbaijan’s problems. Baku is facing economic difficulties that could destabilize the country, and these struggles are a result of a political economy built on a shaky foundation, dependent on petroleum exports. If the government starts losing power because of social unrest and increased opposition to its policies, older, deeper fears may resurface. External powers will start trying to exert their influence over Azerbaijan, which could destabilize the region.

In the short term, this situation could lead Azerbaijan to become more aggressive in Nagorno-Karabakh and to lash out at Armenia in an attempt to deflect attention from its internal woes. In the longer term, if Azerbaijan’s crisis deepens, external powers will compete to dominate the country.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East