By Jacob L. Shapiro

Last Sunday, two missiles were launched at U.S. warships, the USS Mason and the USS Ponce, in the Red Sea. On Wednesday, at least three more missiles were fired at the USS Mason. In both cases the missiles failed to hit their targets. Early Thursday morning, the U.S. retaliated by destroying three radar sites in Houthi and Saleh-loyalist areas in Yemen, according to a statement released by the Pentagon. Anonymous U.S. officials told Reuters that the USS Nitze launched the Tomahawk cruise missiles that hit the radar sites. Reuters reported the sites were located in Ras Isa, on the Red Sea coast.

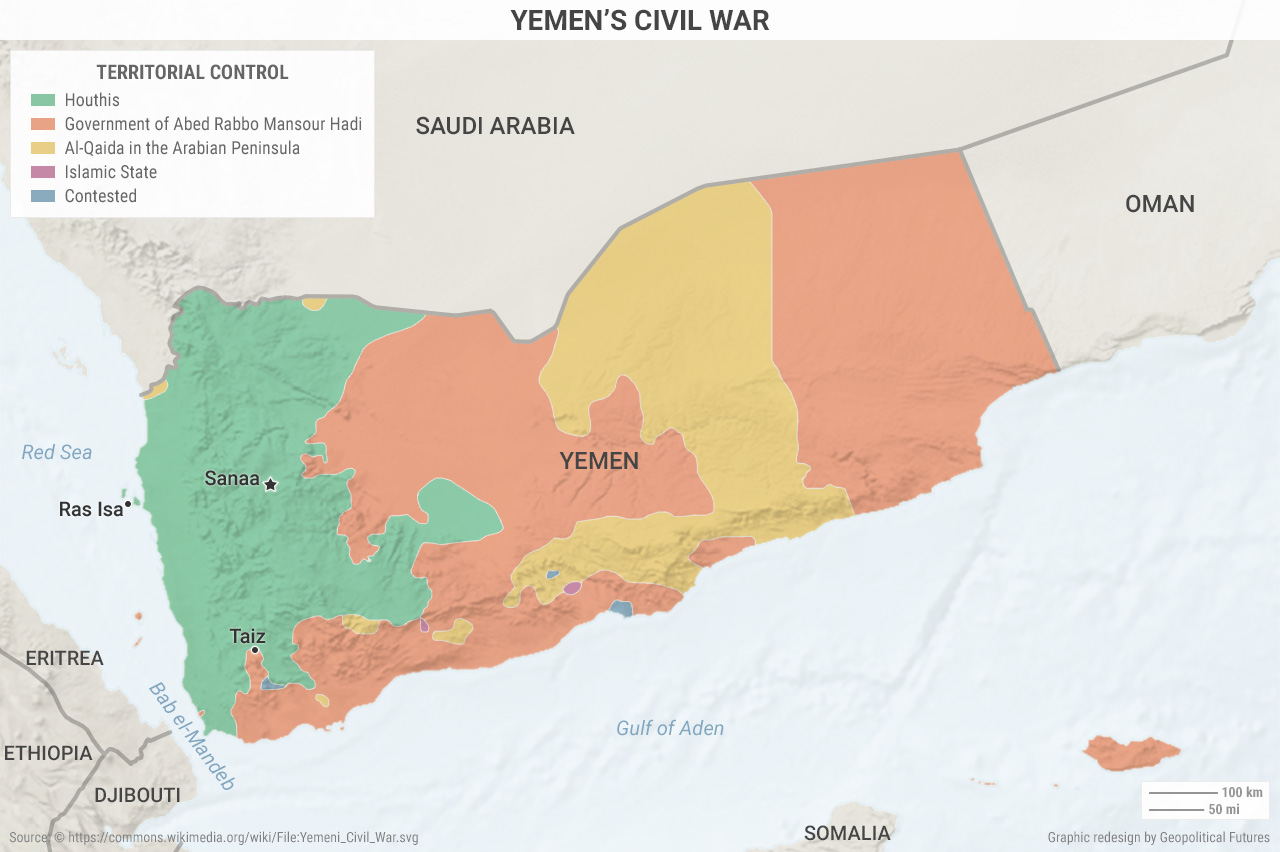

Yemen’s civil war made headlines last weekend when airstrikes hit a funeral hall, killing 140 people and injuring more than 500. Saudi Arabia has not publicly acknowledged its role in that attack, and the White House released a statement afterwards saying that its support of Saudi Arabia’s 18-month-long campaign to defeat the Houthis would be reviewed. It may seem slightly strange that the U.S., just a week after expressing such displeasure with Saudi Arabia, would carry out cruise missile strikes on the very group Saudi Arabia is seeking to destroy. But it is not strange for the U.S. to take offensive action against a potential threat to a key maritime chokepoint in the region.

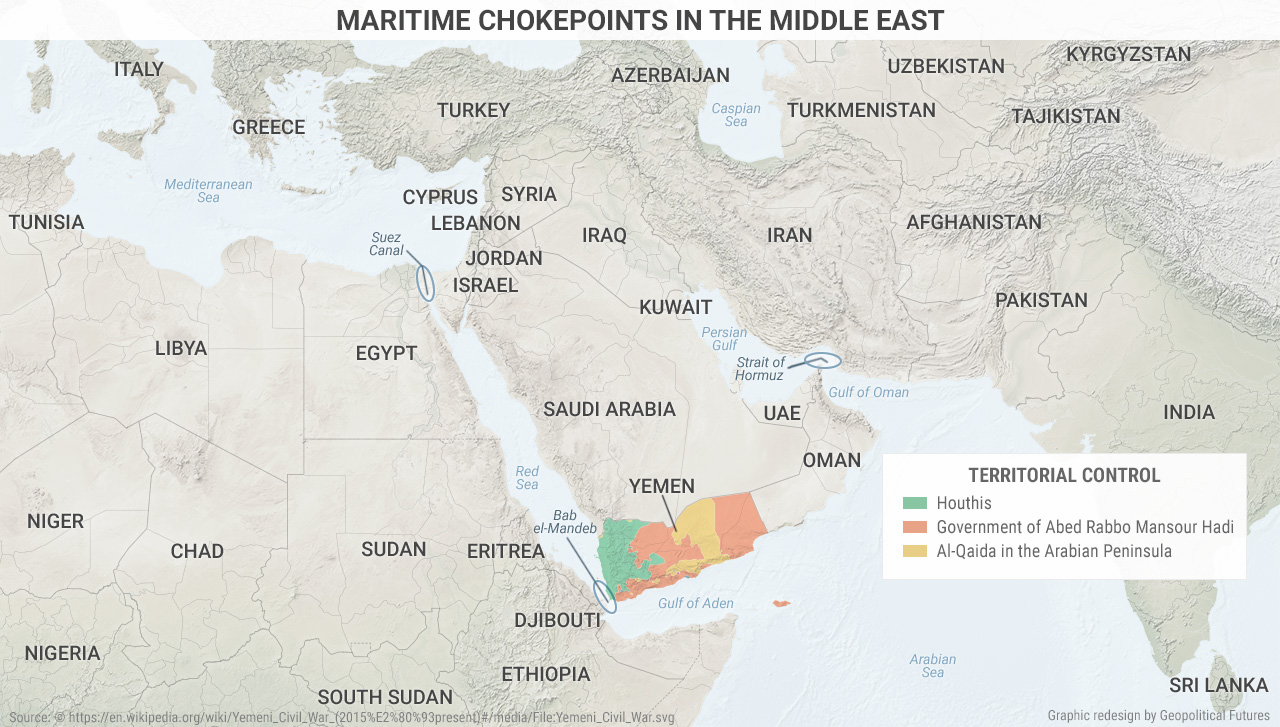

For the U.S., this is not about the Yemeni civil war. It is about making sure maritime shipping lanes are kept safe and open. The Houthis now control territory on the coast of the Red Sea and the Bab el-Mandeb. The Bab el-Mandeb is a strait that at its narrowest point is just 18 miles across. It is impossible to traverse from the Mediterranean Sea into the Indian Ocean via the Suez Canal without going through the Bab el-Mandeb. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and Egyptian government data, in 2014 roughly 10 percent of all global shipping passed through the Suez Canal. The alternative to the Suez Canal route is to go around Africa. For some perspective, shipping from northern Europe to the Persian Gulf would take roughly 10 to 12 days longer if going around the Cape of Good Hope.

The U.S. dispatched three ships to this region at the beginning of October: the USS Mason, the USS Nitze and the USS Ponce. The USS Mason and the USS Nitze are guided missile destroyers, and the USS Ponce is an amphibious transport ship. Just a few days before they arrived, a UAE logistics ship was severely damaged by an attack while operating roughly 40 miles north of the Bab el-Mandeb. The UAE ship was supporting Saudi operations, so it makes some sense that the Houthis would target the ship. Even so, demonstrating the capability and will to damage ships passing near the strait must have caught the United States’ attention. A potential blockage of this strait by militants with access to anti-ship missiles is not acceptable from the U.S. point of view.

The Houthis have repeatedly denied any involvement in the missile attacks on the U.S. ships. They exhibited no such shyness in claiming the attack against the UAE ship, even posting video of the attack on the internet. The Washington Institute analyzed the tape and concluded the Houthi forces likely used a radar-guided anti-ship missile in the attack on the UAE ship, suggesting perhaps it was a variant of the C-802, a Chinese anti-ship missile that the Iranians tried to buy in the 1990s. When the deal fell through, Iran reverse engineered the missile and unveiled it as the Noor missile in 2000 during a series of war games in the Persian Gulf.

It is not clear precisely what missiles were used in the attacks against the U.S. ships, but U.S. officials told the Associated Press they were variants of the so-called Silkworm missile, another type of anti-ship missile produced by the Chinese and sold to both sides of the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war. Iran, which backs the Houthis, produces anti-ship missiles such as the ones used in the attack on the UAE ship, so it is a reasonable possibility that these were also the same types of missiles used in the attacks against the U.S. ships.

Why the Houthis would have attacked U.S. ships is less clear. Perhaps it was a revenge strike for the attack on the funeral hall, or perhaps some Houthi fighters went rogue and decided to take matters into their own hands to punish the Americans. Whatever the case, the U.S. has responded by officially knocking out three coastal radar stations, and unofficially probably knocking out missile storage areas and the firing crews. Shipping sources reported to Reuters at least one additional strike in Taiz province not mentioned in the Pentagon press release. This wasn’t just a warning shot: the USS Nitze fired as many Tomahawks as necessary to eliminate the immediate threat of such missiles targeting ships in the Bab el-Mandeb.

Yemen doesn’t get nearly as much media coverage as Syria. This is in part because the casualty numbers are far lower (the U.N. estimates there have been 4,000 civilian casualties in the fighting as of the end of September). It is also because generally speaking, Yemen is of no real strategic importance to anyone except for Saudi Arabia. That will quickly change if militants can reliably get their hands on anti-ship missiles and make crossing the Bab el-Mandeb difficult.

The Houthis have already demonstrated they don’t want to tangle with the U.S. on this with their enthusiastic denial of involvement, and they are in need of more foreign support right now, not less. Iran also doesn’t need to give the U.S. any reason to increase support for Saudi-backed forces in Yemen, especially after tensions between the Saudis and the U.S. have come out into the open in this conflict. The U.S. and Iran have a complicated relationship in the Middle East, cooperating in Iraq against the Islamic State, on opposite sides when it comes to the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria. Iran enjoys the Houthi thorn in the Saudi side but it’s not about to let a full-blown conflict with the U.S. erupt as a result of this incident, at least not anytime soon.

The more worrying fact is that Yemen has become a haven both for al-Qaida and for offshoots of the Islamic State. The Iran-backed Houthis and the Saudi-backed government of Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi are too busy fighting each other to deal with the situation, and Yemen is a lawless place awash in weapons of all kinds. An attack on U.S. naval assets originating from Yemen cannot help but bring to mind the attack on the USS Cole, which al-Qaida bombed while it was refueling in Yemen’s Port of Aden in October 2000. This has been a trouble spot for decades; it is simply the shape of the threat that changes over time.

The U.S. is already fairly active in Yemen, especially with drone strikes against select targets. But anti-ship missiles being fired at ships in the Bab el-Mandeb is a bigger and more serious threat than usual. The more the U.S. attempts to extricate itself from the region, the more it gets pulled back in. This time it happens to be because a major maritime shipping route has come under direct assault. It is not a threat the U.S. will tolerate and may necessitate a more substantial U.S. presence in the region going forward.