By George Friedman

The Western press has been filled with stories about Islamic State defeats. The city of Ramadi in Iraq was retaken by Iraqi army forces. The Democratic Forces of Syria, an alliance consisting of the Syrian Kurdish YPG militia and several Arab partners, backed by U.S. airstrikes, has pushed westward and retaken the Tishrin dam on the Euphrates river, which had been seized by IS forces several months ago. There has been pressure along the perimeter of the Islamic State’s territory for several months now and there is a growing sense in the media that the Islamic State has reached its high water mark and is now retreating and that in due course that retreat will become a rout.

This of course may prove to be true, but it is premature to regard these defeats as either devastating or definitive. Ramadi was of course a loss but it is unclear just how many men were defending it toward the end. It should be remembered that there is no harder objective than to dislodge a capable enemy from an urban area. Ramadi is a major city with a pre-war population of hundreds of thousands which includes buildings, alleys and parks, and this dense urban environment favors the defenders. In the latest reports, the defenders left behind booby traps throughout the city, so that while IS has abandoned the city, the Iraqi army has not yet secured it.

Bearing in mind the difficulty of taking a city, the victory by the Iraqi army should not be trivialized. However long it took them, they have retaken Ramadi. Nevertheless, viewed from far away, the reports that IS fighters had broken and run at the end do not seem correct. Judging from the numbers that were seen fleeing, it sounds less like a rout, than a covering force holding back the Iraqis while the main force withdrew, and then doing what a covering force is supposed to do, which is get out of town as fast as their legs will carry them.

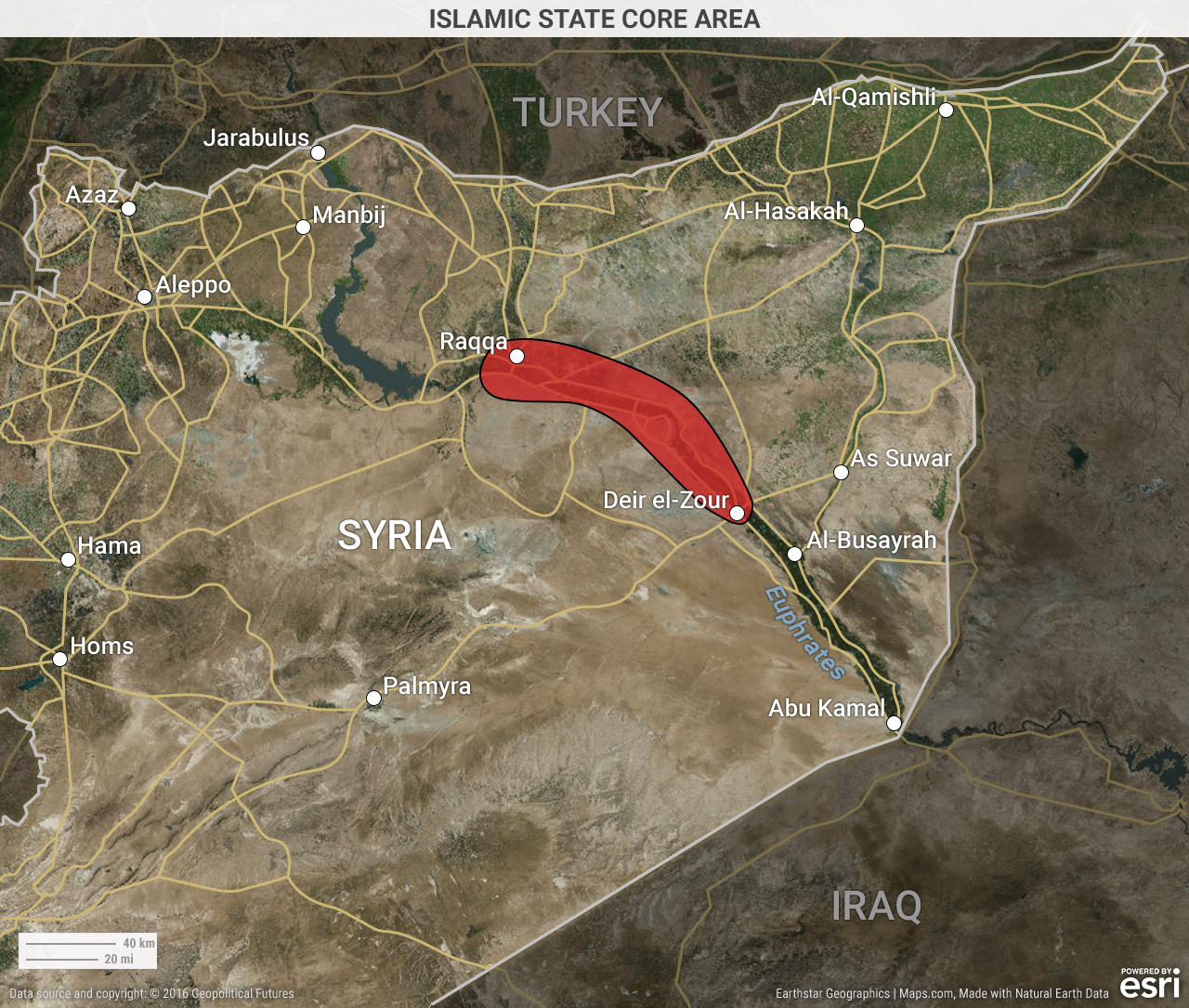

A similar thing can be said about the Tishrin Dam, 56 miles east of Aleppo, that was taken in Syria. There is another dam, along with a power plant, about 10 miles to the south, which supplies power for Raqqa, IS’ power base. That is the dam to take, along with the road to Raqqa. The Kurds may have simply overwhelmed IS. Another option is that IS fought the Kurdish-led coalition in order to delay and tire the alliance’s troops, and retreated to prepare its positions to defend the second, more significant dam.

The point is that without knowing the details of IS’ activities in the weeks and days before the victory, it isn’t clear whether this was a major defeat or even preparation by IS for a new offensive elsewhere. IS has a large but finite force. In order to mass a reserve to throw in new directions, it has to thin out its lines. This inevitably leaves vulnerabilities and its enemies exploit those vulnerabilities. As Frederic the Great put it: “He who defends everything, defends nothing.” This could be a rationalization of lines, preparation for an offensive or the beginning of the collapse of IS. We don’t know. But it seems to us that if it is a collapse it is an odd one. In watching collapsing armies, whether the Wehrmacht in 1945, the Egyptians in 1967 or the Iraqi forces in 2003, there are certain hallmarks of collapse. The most important of those is large scale surrenders and large numbers of small groups of soldiers trying to avoid captivity by making their way home.

Tens of thousands of soldiers collapse in predictable ways, and we have not seen that collapse with IS. It may be true that it is weakening, but if so, it is doing that in a fairly disciplined fashion. There are no reports of large numbers of captives, nor of disorderly movements of small numbers of troops. If these were defeats then they resemble very orderly defeats. As I have said the measure of an army is in defeat. If it can survive defeat, regroup and attack, it is a significant force. This is what the U.S. army did at the Battle of the Bulge. A massive defeat there was the preface to victory.

It must also be remembered that war is a matter of morale, both military and civilian. The ability of IS’ enemy to convince that IS is failing can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The Americans and Iraqis will use these events to create a sense of despair among IS and enthusiasm among allies. IS, as we have seen from the audio message of its leader, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, will acknowledge defeats — never lie about something that everyone already knows — while making clear a calm resolve. Along with the shooting, wars are determined by psychology and psychology is determined by the management of perceptions through the presentation of information — or disinformation.

We must also remember that there will be a second phase of this war if IS’ conventional forces are defeated. The Taliban in 2001, facing massive American strategic bombardment, decided to abandon large formations and cities, retreating, regrouping and reemerging as a guerrilla force. This is a force that appears to be perhaps winning the war the U.S. declared it to have lost in the winter of 2001-2002. Similarly, the collapse of the Iraqi army in 2003 was a preface for key commanders launching an insurgency that ultimately fought the U.S. army to a standstill, a struggle in which the rate of attrition on the American side was not worth the prize.

The United States is outstanding at fighting conventional wars, whose purpose is to defeat a conventional army. IS has taken territory and that means its military must have conventional organization. The Islamic State is also betting that the U.S. will not send sufficient main forces to be able to defeat it. But if it is defeated as a conventional force, IS will evolve into a kind of force that the U.S. is not good at fighting. It will withdraw, disperse and re-emerge as insurgency that does not hold territory, and picks its engagements on its terms and in its time.

It is noteworthy how rapidly moods change. The reality is that we do not know clearly what forces IS deployed in the recent battles, its motivation for leaving the battlefield, nor the state of morale and discipline in the IS forces. They may be on the ropes, but I doubt it. They might wind up there, but the manner in which they fought these battles — again seen from afar — does not allow us to draw the conclusion that they are being slowly beaten. In the past, they have been excellent at the central art of war: surprise. They know the value of surprise and it is unlikely that they will go quietly into that good night, if indeed that is where they are going. Given the defeats, we need to be watching IS’ next move before we draw conclusions.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East