By Lili Bayer

Six years ago, George Friedman predicted that, caught between Russia and Germany, the countries of the intermarium – the region between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea – will be forced to form an alliance. These are the borderlands where successive empires have vied for influence, and where states have found themselves time and again at the center of geopolitical fault lines – between the Ottoman, Habsburg and Russian empires, between Germany and Russia, and between East and West during the Cold War.

Earlier this week, we examined the tectonic shifts underway in Turkey. Faced with a hostile Russia in the north and myriad forces fighting over pieces of a broken Syria in the south, the government in Ankara is coming to the realization that it needs to move closer to the United States and allies in Eastern Europe like Poland and Romania in order to mitigate its security threats. But Turkey’s search for allies is not limited to countries to its west and north: there are now indications that Ankara is pursuing a stronger defense relationship to its east, with Azerbaijan and Georgia.

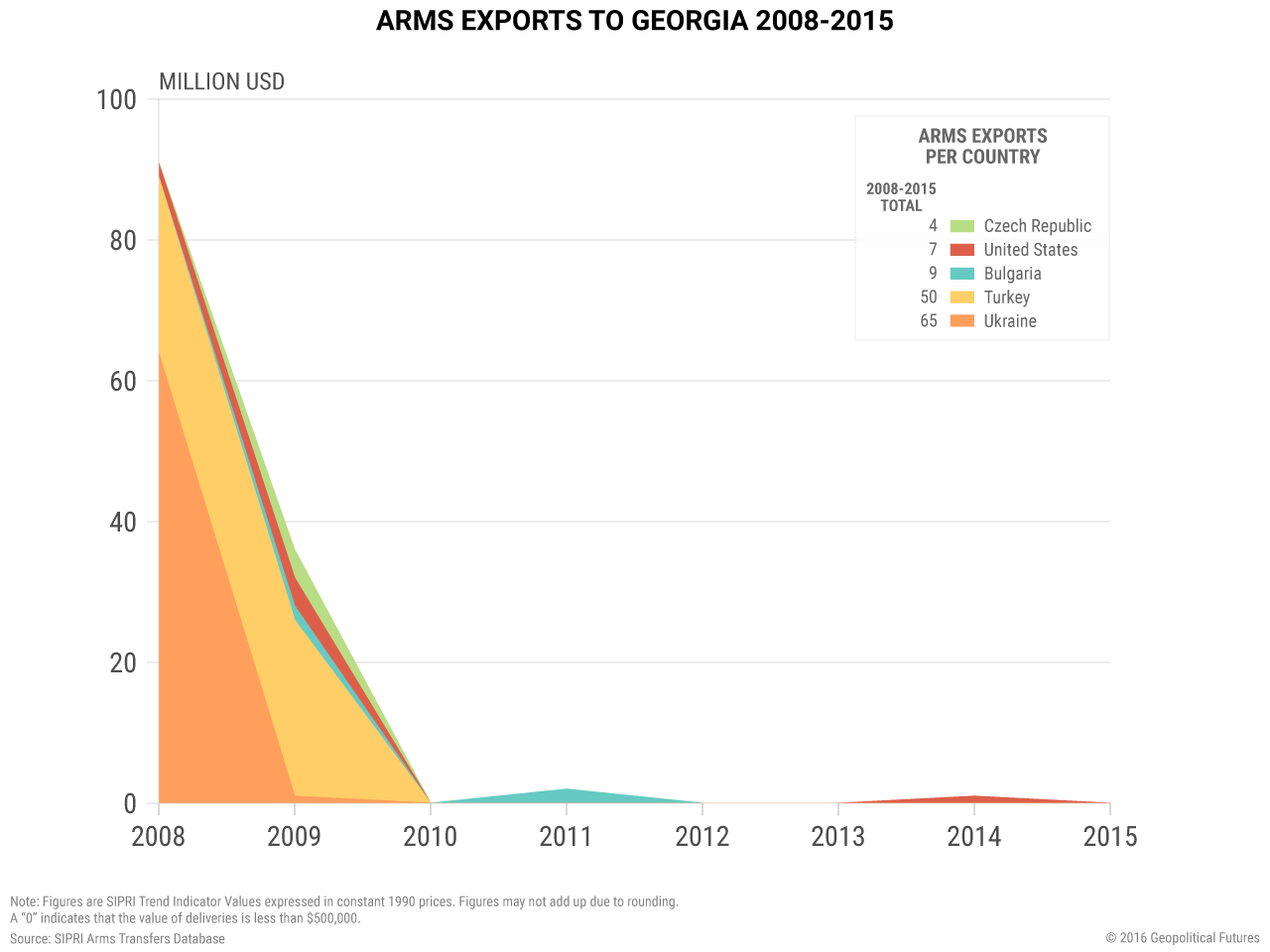

Georgia, on the eastern edge of the Black Sea and bordering Russia to the north, is a natural fit for an alliance that includes Black Sea powers Ukraine, Turkey, Romania and Bulgaria. Georgia is a small yet vocal opponent of Moscow. The government in Tbilisi fought a war against Russia in 2008 and has few hopes for recovering control of its two Russian-backed breakaway regions, South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Georgia’s geography has dashed the country’s dreams of NATO membership and EU integration. The U.S. may engage in technical and limited defense cooperation with Georgia, but Washington is not willing to take responsibility for the defense of a country with long-standing territorial disputes in Russia’s backyard.

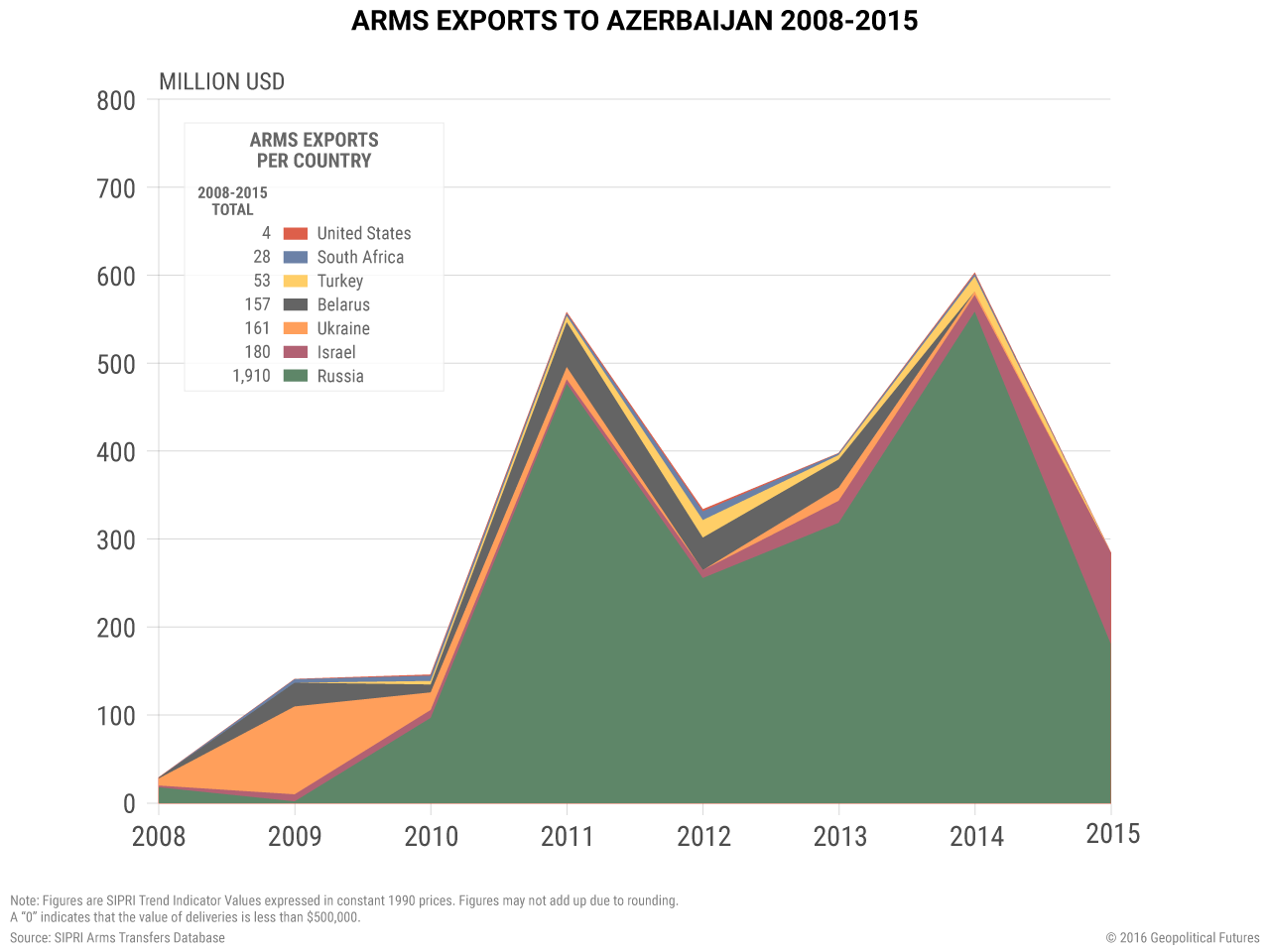

Azerbaijan, like Georgia, has a breakaway region, Nagorno-Karabakh. With Russia to the north, Georgia and its archenemy Armenia to the west, Iran to the south and the Caspian Sea to the east, Azerbaijan occupies a highly strategic geographical position. Baku’s political position is much more nuanced than that of Tbilisi. As Azerbaijan’s economy until recently boomed with oil wealth, the country was able to use its energy resources to build various political and defense relationships, from Washington to Moscow, Ankara and Jerusalem. Despite Russia being the patron of Armenia, Baku and Moscow have cooperated closely, with Russia acting as the largest provider of arms to Azerbaijan.

Ankara has long enjoyed close cooperation with Baku, and has been holding military exercises with both Azerbaijan and Georgia since 2012. Nevertheless, over the past two years, three crises have emerged and transformed the priorities of these three countries. First, Russia’s annexation of Crimea and sponsorship of a separatist campaign in eastern Ukraine sent shock waves throughout the region. Second, the Islamic State became a formidable force in Iraq and Syria. For Turkey, developments in Ukraine raised fears of Russian aggression in the Black Sea, while the Islamic State presented a threat to Turkish aspirations in the Middle East. Meanwhile, in Azerbaijan, the fall in oil prices created a financial crisis and threatened to undermine the position of the regime. The leadership in Georgia, watching Moscow in fear, hoped that the West’s new efforts to boost defense along NATO’s eastern edge and deter Russia could lead to greater defense assistance and cooperation with the West, which it has been coveting for years.

These new realities created a new context – and heightened impetus – for a strong trilateral alliance between Turkey, Azerbaijan and Georgia. Turkey needs more buffers when it comes to Russia. Azerbaijan is no longer in a position to curry favor with all powers and is in search of close protectors. For example, Russia is still the largest arms exporter to Azerbaijan, but in 2015 Moscow’s arms sales to Baku fell by nearly 70 percent. Georgia, moreover, is happy to strengthen ties with any country that opposes Moscow. Since August 2014, the defense ministers from Azerbaijan and Georgia have been meeting twice a year to discuss cooperation, and on May 15 a summit involving the two countries and Turkey led to the announcement of new trilateral military exercises, to be held in Georgia in 2017. At the same time, Georgia has offered Azerbaijan the opportunity to make use of training programs provided by the NATO-Georgia Joint Training and Evaluation Center. While the alliance formally involves only the three countries, their activities will likely be in close cooperation with NATO – and the U.S.

These plans, if they come to fruition, provide us with another strong indicator that a pro-Western alliance is taking shape from Estonia in the north to Romania and Bulgaria along the western edges of the Black Sea to Turkey, Azerbaijan and Georgia in the south. Earlier this week, Ukraine and Turkey signed a military cooperation agreement. Romania, Poland and Turkey are in close discussions over increasing cooperation. At the same time, the U.S. and NATO are in the process of boosting their presence in the Baltics and Central Europe.

Last week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan raised the specter of the Black Sea becoming a Russian lake, due to NATO’s limited presence in the region, in his view. But these new alliance structures signal that, if anything, Russia will be surrounded in the Black Sea and that an alliance to counter Moscow – the intermarium – is emerging.