By Jacob L. Shapiro

One of the questions we receive most often from our readers is: Why will the U.S. not offer the Kurds more support? Some suggest the U.S. could supply the Kurds with better weapons and more military assistance, others go so far as to ask why the U.S. doesn’t put more pressure on Turkey to give the Kurds independence. But many see that the Kurds have proved themselves to be excellent fighters and willing contributors to the fight against the Islamic State, and so the Kurdish question has become routinely debated in the U.S. In President-elect Donald Trump’s own words earlier this year on the campaign trail, “the Kurds have to be brought into it, because they’re good fighters and we treat them terribly, and they’re the ones that really seem to be the ones that fight.”

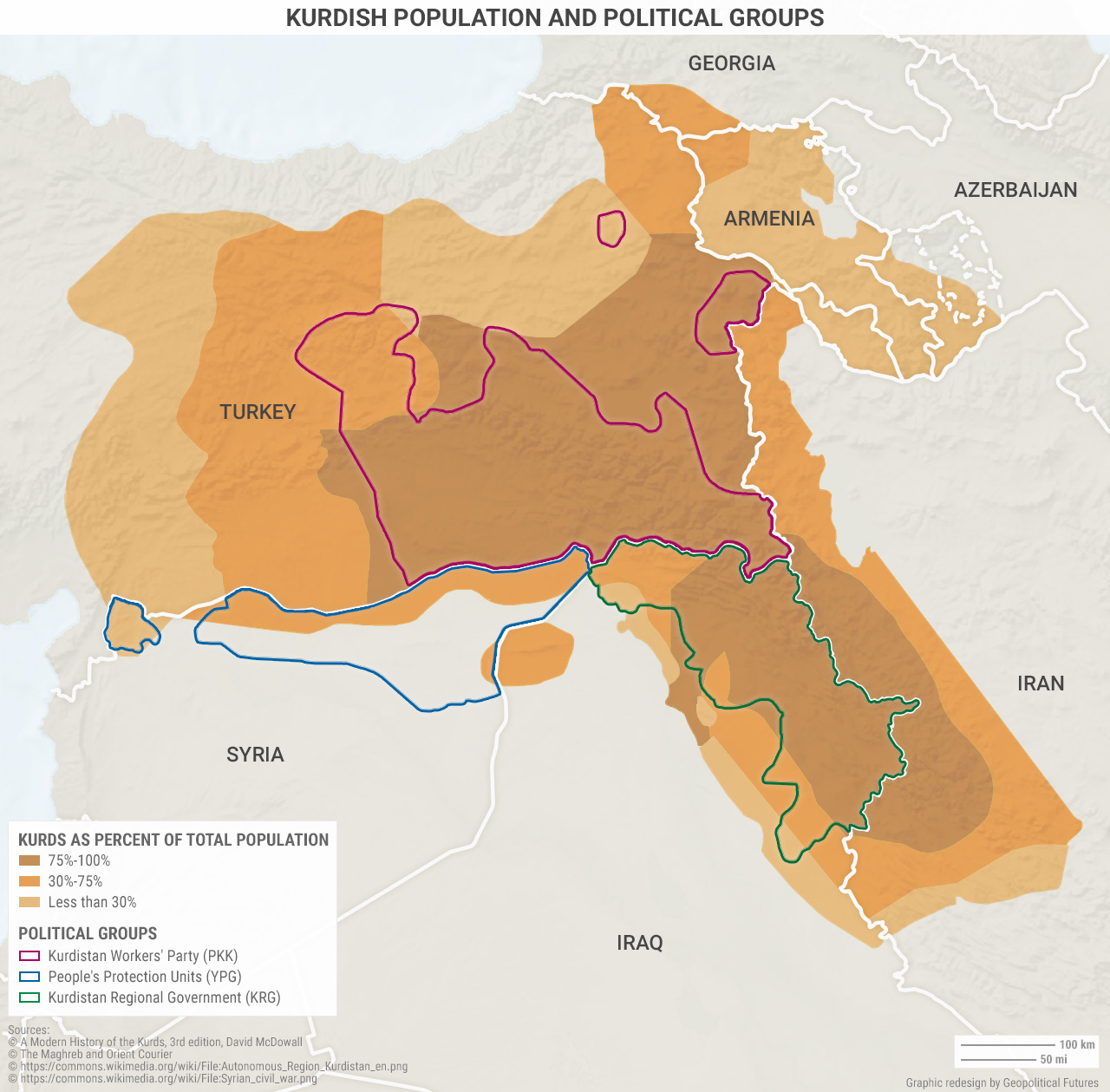

As with all questions, there are both short answers and long answers; the goal here is to give a relatively short answer. This inevitably means that certain facts and developments will be omitted, but for those who feel short-changed, we promise to follow up with a more comprehensive study in due course. We need to start by stating that there is no such thing as “the Kurds.” There are Syrian Kurds, Turkish Kurds, Iraqi Kurds, Iranian Kurds and others as well. There are well over 100 Kurdish tribes throughout Kurdish-inhabited areas in the Middle East alone. There are Kurds who speak Kurmanji, Sorani, Pehlewani, Gorani and a number of other languages and various regional dialects. There are Sunni Kurds, Shiite Kurds, Jewish Kurds and Yazidi Kurds.

The media likes to repeat the line that the Kurds are the world’s largest stateless nation, and while it is impossible to get a precise number, most sources estimate there are between 29 million and 35 million of them. There are two problems with this. First, the Tamils, who live mostly in India and Sri Lanka, might have something to say about the idea that the Kurds are the largest stateless nation in the world, as there are almost 80 million Tamils. But the second and more fundamental problem is that it is an overly simplistic way of looking at a diverse group of people who share a number of things in common but who are also very different from each other.

Kurds in Turkey celebrate waving the Iraqi Kurdish Regional Government’s (KRG) banners as a peshmerga fighters convoy crosses through at the Habur border along the Turkish-Iraqi border with heavy weapons on Oct. 29, 2014. ILYAS AKENGIN/AFP/Getty Images

Language is one notable example of these differences. A common language is one of the basic building blocks of a national culture, and the various communities of Kurdish people in the Middle East and beyond do not share one. The two most common Kurdish languages are Kurmanji and Sorani, and while they are related, linguistic experts have compared the difference between their grammatical structures to the difference between German and English. Furthermore, they employ different scripts: Kurmanji is usually written in Latin script and is spoken in Turkey, northern Syria and Iraq; Sorani is written in Arabic script and is spoken in much of Kurdish Iraq and western Iran. The Kurdish languages also do not have an extensive written tradition; writing systems were standardized only in the 1920s, when the first stirrings of Kurdish national awareness were emerging. On this most basic level, it is hard to speak of a mature Kurdish national identity.

Besides the differences in language, another important element to keep in mind is that Kurdish affiliations are still much more tribal than they are national. This is not to say that Kurdish nationalism doesn’t exist – it does, and it has a diverse range of manifestations. But the Kurdish peoples have never really had an independent state, and that is because the “state” has never been the ideal organizing principle of Kurdish hierarchy. The only independent Kurdish state of the modern era was the short-lived Republic of Mahabad, which was located in present-day Iran. But this exceptional and obscure piece of history just confirms the importance of tribal ties, rather than nationalist sentiments or formal state structures, to the Kurds.

Mahabad emerged because the Soviet Union supplied it with significant military and economic assistance. The leaders of Mahabad, including Mustafa Barzani, the father of the current president of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), used this aid to buy the loyalty of neighboring tribes. As part of the negotiations at Yalta, where ironically for these Kurds Josef Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt discussed the future of a post-World War II world based on principles of national self-determination, the Soviets agreed to withdraw, and Mahabad was reabsorbed into Iran without strong resistance. Many Kurdish tribes welcomed the reabsorption because without Soviet aid, the economic conditions of the fledgling republic rapidly deteriorated. In a tribal system, people’s loyalty is with their kin and their leader because the tribe provides for and defends its members. The transition from tribe to state requires that tribal leaders give up those powers and agree to work within a political framework, and the idea that the diverse population of the Middle East’s Kurdish groups are going to do that is little more than fantasy.

This is reflected in the current political divisions in the Kurdish world today. The situation is immensely complicated in Iraq, where the KRG is in a state of paralysis for two reasons. First, current President Massoud Barzani refuses to step down from his position. Second, the financial situation in the KRG is awful, and Barzani’s “government” increasingly lacks the necessary funds to sustain the various patronage networks that make the KRG function. There are two main political parties in the KRG: Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). These two factions fought a civil war in Iraq in the mid-1990s, and Barzani and the KDP even called in Saddam Hussein – the same man who oversaw the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Kurds at the hands of his Iraqi army in the late 1980s and early 1990s – to help the KDP defeat the PUK. The two sides aren’t at war now, but that is about the most that can be said. They still fiercely compete for political control in the KRG.

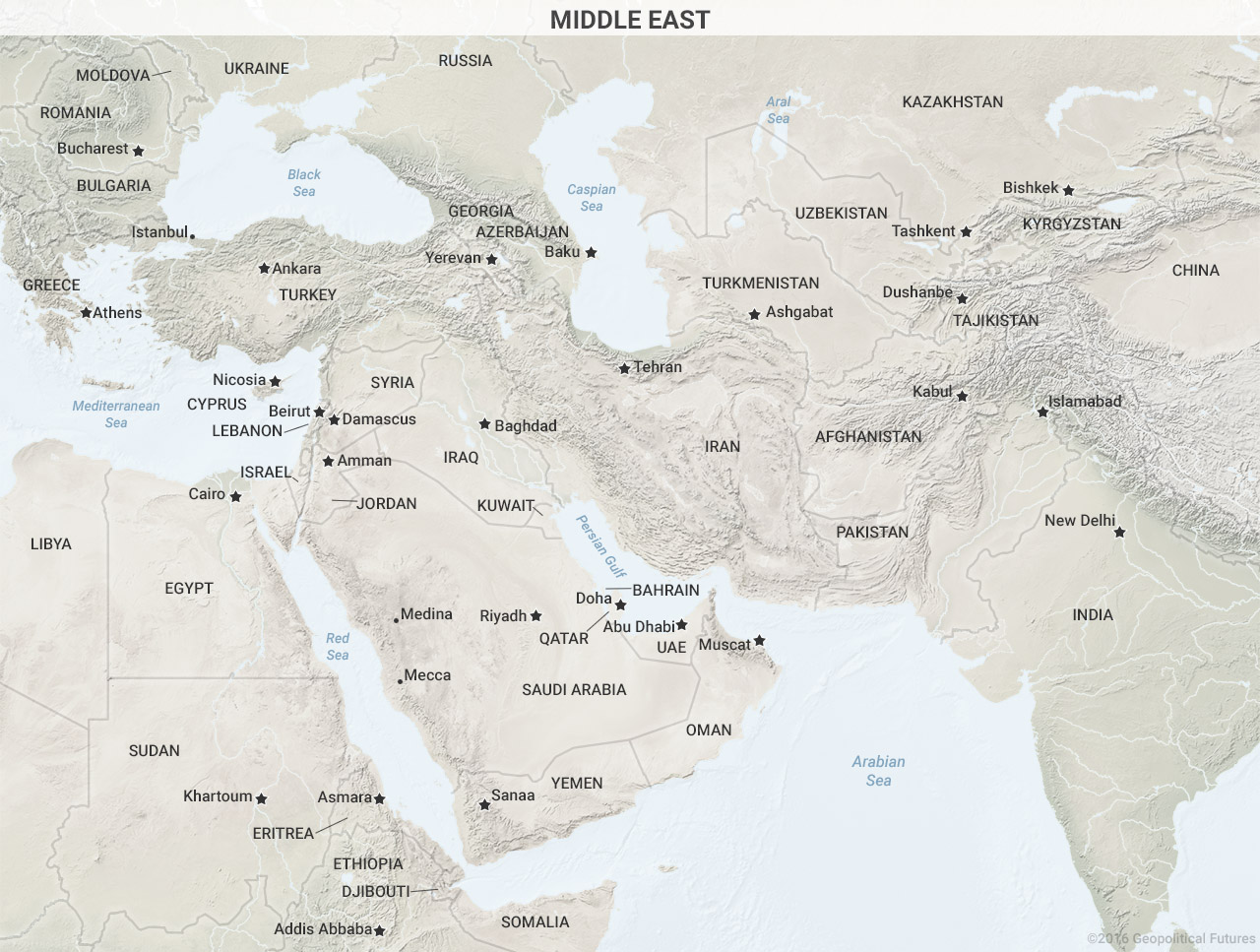

Meanwhile, Syria’s Kurds, led by the People’s Protection Units (YPG) militia, have much more in common with their Kurdish cousins residing in Turkey (to whom they are more closely related) than with the various clans and tribes that support Barzani and the KDP. As a result, Syria’s Kurds fight IS in Syria, the KRG’s peshmerga fight IS in Iraq, and the two Kurdish groups now also compete against each other for control of terrain in the areas around the old Syrian-Iraqi border, which has become a fluid border between different strains of Kurdish political and military control. Looming over all of this is Turkey, which has the largest Kurdish population in the world by far. Turkey has been fighting a sporadic Kurdish insurgency within its own borders for decades now, in part because Turkey has no interest in granting these areas further autonomy, let alone independence. And yet Turkey maintains an excellent relationship with the KRG, which relies on Turkey for investment and access to land routes to export KRG oil to the world when Baghdad is not cooperating. The KRG has also invited Turkish troops into northern Iraq outside Mosul, much to the chagrin of the Iraqi government.

The problem is that there really is no good word in the English language to describe who and what the Kurds are today. They are not quite a nation, and yet they are more than an ethnicity. Historian David McDowall has noted that before the Kurds began to define themselves ethnically around the 17th and 18th centuries, the term “Kurd” referred more to a socioeconomic class of nomadic tribes who moved from the mountains that define the borders between Turkey, Syria and Iraq, to the various plateaus around them. This definition remains part of Kurdish culture today even as it becomes more settled and less nomadic.

One thing the Kurds do all share in common is the mountains, a geographic feature that gives Kurds a common perspective as well as a reason so many different pockets of Kurds have developed. “The Kurds have no friend but the mountains” is a common Kurdish expression that seems to exist everywhere Kurds live. When things get difficult on the plateaus and the plains, the Kurds retreat into the mountains’ defenses. One Kurdish myth about the beginnings of the Kurdish people describes the Kurds as descendent from children who fled into the mountains to hide from Zahhak, who is either a terrifying dragon, a child-eating giant or an evil king bent on oppression. Zahhak is also a fairly common character in ancient Persian mythology, which perhaps says something about Kurdish origins as well.

The myths of Kurdish origins may seem a silly place to end, but in some ways it is the most revealing, because for all of the Kurds’ differences, there is a common perspective, as well as a growing awareness of what it means to be Kurdish in a Middle East where old borders are crumbling left and right. The Balkan Peninsula is another place where the mountains have always imparted a deep, almost mystical fascination, but no one would confuse Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks and Montenegrins – whose languages are more similar to each other than Kurdish languages are today – as members of the same nation. Despite the Kurds’ internal differences, there is undeniably a group of people today who all identify as “Kurds” one way or another, even if those ways mean vastly different things to different groups.

Independence is not something that can be “given” to the Kurds. Self-determination is won, not bestowed. If some kind of unified Kurdish national identity were to emerge, it could become a powerful force. But there is no guarantee that this vision of a united, independent Kurdistan will ever come to pass, and if it does, it will happen slowly over decades and perhaps even centuries. New nations can and do emerge over time, but they are not forged overnight, and in the meantime the U.S. requires partners of sufficient reliability and power to manage the Middle East’s instability without the constant presence of U.S. troops. Right now, that means the U.S. must rely on Turkey and Iran, neither of which are interested in a meaningful Kurdish independence movement (or movements for that matter). Another comment Trump made about the Kurds during his campaign was that the U.S. “should be using and utilizing those people.” The U.S. will continue to do just that, and little more. The Kurds have no friends but the mountains.