The U.S. National Security Strategy released earlier this month contained a couple of related priorities that have informed recent U.S. actions abroad: reducing U.S. exposure to the Eastern Hemisphere and focusing on its strategy for the Western Hemisphere. Since the U.S. cannot fully disengage from the Eastern Hemisphere, it must end or at least improve hostile relationships that have drawn Washington into several costly and failed wars there – all while maintaining critical economic relations. Efforts toward that end are underway but far from final.

As important, the new strategy tacitly demands more active engagement in the Western Hemisphere, the point of which is to assert U.S. security dominance and dramatically enhance the economic capabilities of Latin America so that the U.S. can disengage from the Eastern Hemisphere. For that to happen, Latin American nations must become more politically stable and economically productive.

After World War II, the U.S. based its national security on the reconstruction of Eastern Hemisphere countries in Europe and Asia. There was a security component to its strategy, of course, rooted as it was in Cold War logic, but it also evinced a less conscious reality: Successful, developed economies will eventually incur higher wages and higher costs such that national economic growth doesn’t necessarily mean economic well-being for its people. To keep costs down, countries import cheaper products from less developed economies. Such was the case for Europe and Japan. “Made in Japan” made consumption more affordable in much of the Western world, but as Japan matured and prices rose, China became the go-to source for lower-cost production. Coupled with U.S. investment, this fueled China’s economic rise. This was not so much a conscious policy but a matter of fiduciary responsibility.

Wealthy economies need low-cost imports from less prosperous countries, but excessive dependence on those imports gives the exporters political leverage as they evolve economically and geopolitically. As China has matured, the U.S. addiction to Chinese goods is now more dangerous and more damaging to the U.S. economy.

In this context, Washington’s renewed military focus on Venezuela is thus linked to an unintended evolution of not only the military dimension of geopolitics but also the economic. The geopolitical logic is that greater economic growth in Latin America will reduce vulnerabilities in the Eastern Hemisphere and, in time, could moderate immigration to the United States. This would require greater political stability in certain Latin American countries.

The broad imperative, to a great extent, is clear. The tactical imperative – that is, what steps Washington needs to take to achieve its goals – is not. Even if Latin American countries benefit from this in the long term, their political systems will be substantially unstable in the short term. One may ask what right the U.S. has to impose itself on Latin America. That is not an unreasonable question, but human history is the history of such impositions.

Some Latin American political economies are based on the export of narcotics, and the exporters – the cartels – have created economic and political systems that make broader economic evolution impossible. Aside from its impact on American life, the drug trade undermines the development of more diverse and powerful economies.

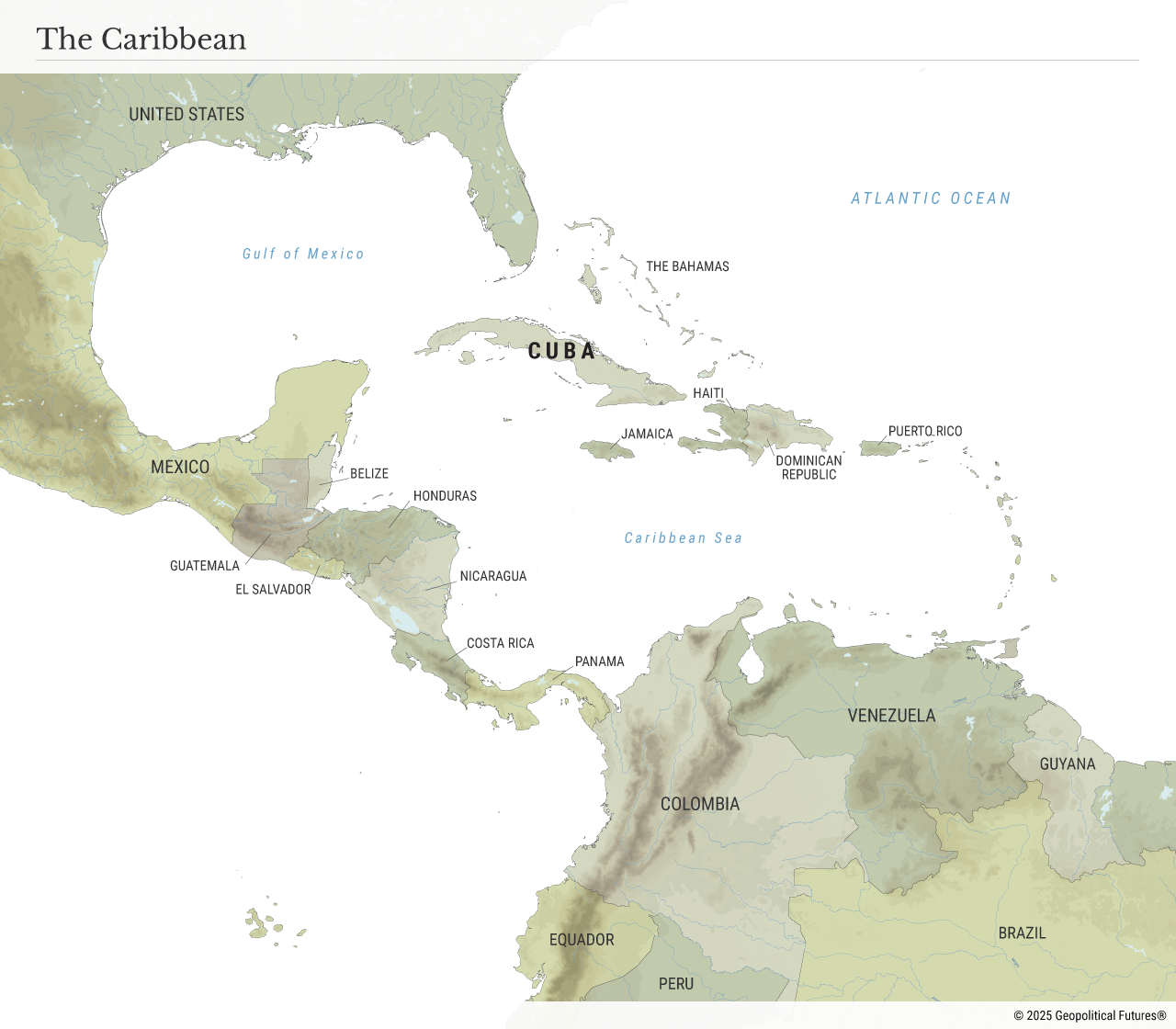

The ongoing military operations in the Caribbean are a first step toward that end. A massive U.S. military force has been deployed to weaken and destroy cartels and thus their military and economic power. The focus on the cartels is intended both to stop the flow of narcotics into the U.S. and to allow the implicit wealth of Venezuela to emerge – not as an act of kindness but as an act of U.S. interest.

But there is an oddity in the tactics being used. The amount of force deployed in the Caribbean is far more than is necessary to blockade Venezuela. It is also far less than would be required to invade and occupy Venezuela, a necessary precursor to destroying the production of drugs in the Venezuelan hinterlands. But the deployment can be understood by considering another dimension of the American problem: Cuba. Cuba has been a potential problem for the U.S. for about 65 years, ever since Fidel Castro established a communist regime. In moving to reshape Latin America, Washington must address the Cuban problem. When the U.S. was considering sending long-range Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine, for example, Russia was in the process of signing a new defense agreement with Cuba. The message was clear: If the U.S. delivered Tomahawks, Russia might send similar munitions to Cuba. The forces deployed in the Caribbean, then, have two uses: unseating Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and thus disrupting the cartels, and threatening Cuba.

Cuba became an economic disaster marked by massive failures of its electrical system and frequent scarcity in many basic necessities. But for all its failure, Cuba poses a real strategic threat to the U.S., given its relationship with Russia – which to some extent is shared by Venezuela. The potential (if hard to imagine) presence of Russian forces in Cuba is a threat to U.S. trade routes and national security.

If the U.S. wants to energize Latin American economies, it must deal with Cuba, which continues to carry out operations in Latin America, despite its economic hardships, and has a loose relationship with Venezuela. Cuba’s intelligence services help protect the Maduro government, and Caracas is by far Cuba’s largest supplier of oil. The recent seizure of oil tankers shows American intent to sever these supplies and thus disrupt both economies.

There is a strategy emerging in Washington and, with it, a more detailed tactic the government plans to use to achieve its goals. If this analysis of U.S. strategy is correct, then the strategy requires dealing with Cuba, toward which the blockade of oil from Venezuela is a rational step. For the strategy to move forward, Cuba, not Venezuela, should be the priority because it would address the potential, if unlikely, threat of a significant Russian presence close to the U.S. mainland.

The shift in U.S. attention to the Western Hemisphere and the extension of the oil tanker blockade of Venezuela, along with the size of the U.S. deployment, seem to be tactical movements in a much broader plan that was stated in the National Security Strategy. Washington has announced its intentions, and now it’s following through.