The release of the 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy has brought into focus a fundamental tension that has been simmering since before President Donald Trump took office: the understanding between the United States and Europe that the geopolitical system that emerged from World War II was to be permanent. The National Security Strategy essentially says that this geopolitical relationship is obsolete, resulting in a sense that the U.S. has betrayed Europe. Thus is Europe’s crisis. In assuming that U.S. security guarantees were an enduring feature of global geopolitics, the Continent, as a whole, has made little effort to guarantee its own security.

U.S. guarantees were a direct byproduct of World War II. After 1945, the Soviet Union occupied and installed communist regimes in Eastern Europe. U.S. and British allies occupied Western Europe and formed a variety of democratic systems. The division left Western Europe extremely vulnerable to Soviet military action.

The U.S. did not want the Soviets to take control of Western Europe – something Moscow could easily have done after 1945 – in part for ideological reasons. Western capitalism was directly at odds with Soviet communism. But it also opposed the Soviet Union for strategic reasons. The foundation of U.S. national security (argued persuasively by strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan) was the command of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The U.S had no military threats in the Western Hemisphere; the only threat lay half a world away. Recall that the U.S. did not enter World War I until German U-boats sank the Lusitania. The death of the Americans on board triggered an emotional response, of course, but as important, it brought to the fore the threat Germany posed in the Atlantic. The British navy had already secured the Atlantic, but it had done so without threatening the U.S. or interfering with its trade. Germany’s maritime strategy, if successful, would have thus created an economic problem because Washington could not assume Berlin would allow it to trade unimpeded. Hence, the U.S. joined the war effort.

World War II – in some ways merely a continuation of World War I – presented the same dilemma. If Germany defeated the United Kingdom, the German navy (now in possession of British assets) could hold the Atlantic hostage. It could even use the Atlantic to invade the U.S. mainland. The Lend-Lease Act was predicated on that dilemma. The agreement stipulated that the U.S. would not enter the war but that it would help arm the United Kingdom so that it could defeat Germany and thus maintain its maritime primacy. Crucially, Lend-Lease also contained a secret guarantee: If the British were likely to be defeated, their navy would not fall into German hands and would sail to Canada and protect the U.S.

Then came the attack on Pearl Harbor. Japan appeared ready to take control of the Pacific Ocean, while one day later, Berlin declared war on the U.S. This meant the U.S. faced war on two oceans, dispelling the idea that the oceans protected the U.S. from attack. Command of the sea was no longer a passive reality of distance but a matter of strategic expedience.

Thus was the strategic foundation of the Cold War from the U.S. point of view. Having faced threats simultaneously in the Atlantic and the Pacific, and having sought to avoid involvement in the war, the U.S. realized it had to constantly maintain a military force that could command both oceans.

This principle also informed U.S. opposition to the Soviet Union. If Moscow occupied Western Europe, it would have held Western European ports on the Atlantic. If the Soviets developed a proper naval force, the U.S. would face another existential threat. Preventing the Soviets from taking Western Europe, then, was a fundamental strategic imperative. In this way, Washington’s commitment to Europe was a moral, ideological and strategic project. The concept of mutually assured destruction made nuclear war unlikely, but a conventional war was always possible. Guaranteeing Europe’s security was far easier than engaging in a potential naval war for command of the Atlantic. And so Washington was happy to nurture the concepts of NATO and other collective institutions. Given the ravaging of Western Europe that left it economically destitute and militarily impotent, the U.S. had to create a new strategic reality. Hence, the deployment of major force in Western Europe and financial support to make Europe economically viable.

This reality remained in place even after the Soviet Union collapsed. But it has not survived the Russian invasion of Ukraine. To be sure, the invasion has been a failure. Russia intended to occupy all of Ukraine but managed to take only some territory in the east. From the U.S. point of view, the war has demonstrated nothing less than Russia’s military obsolescence. And if the Russian military is obsolete, then so too are U.S. security guarantees to Europe. Put simply, it was in Ukraine that the Cold War truly ended.

There is, of course, a parallel dimension to this new reality. In 1945, Europe was unable to defend itself economically. That is no longer the case. In 2024, the European Union’s gross domestic product stood at about $19 trillion – collectively larger than the GDP of China. That it does not wish to spend money on defense means it does not recognize the obsolescence of U.S. guarantees. The sense that Washington is abandoning Europe assumes that the U.S. had a permanent obligation to defend Europe even when there was no ideological, military or economic threat. Russia may well become a threat in the future, and if that’s the case, there is plenty of time for Europe to prepare to defend itself.

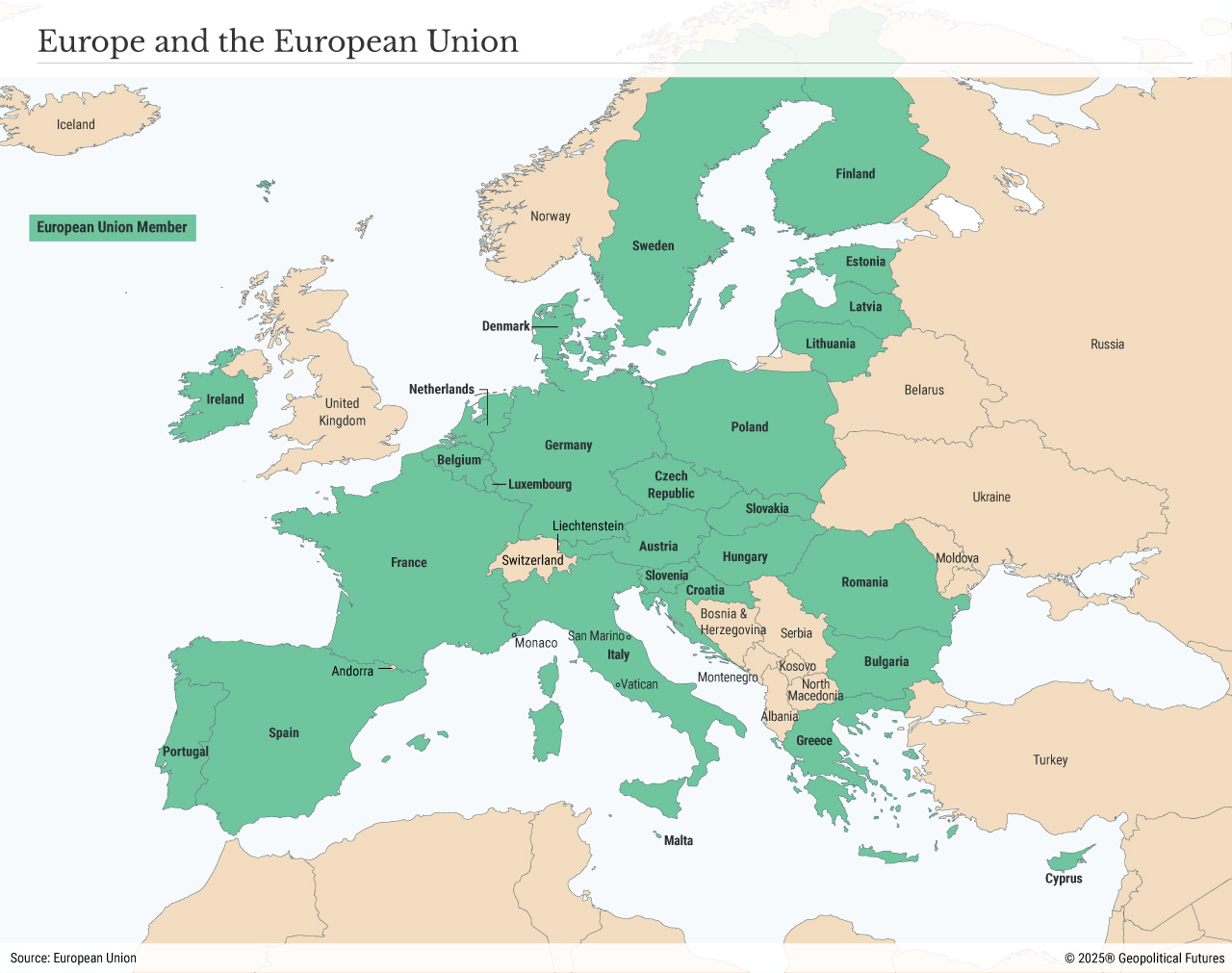

The problem is that there is no such country as Europe. The European Union consists of 27 sovereign states. These nations speak different languages, have different cultures and harbor ancient distrust of one another. When the question “What will Europe do?” is asked, it assumes that Europe is an entity that makes decisions for the whole. In fact, Europe was and still is only a continent, an abstraction in an atlas. Individual European countries are relatively weak, compared to the Continent as a whole, and consist of once and potentially future enemies that constitute an ancient and hostile geopolitical system of various economic and military powers. In large measure, these nations need, but are unable, to merge into a single state with each country organized as a province with a degree of autonomy, having a central government and legislature. Europe seems unable and unlikely to build a military that would be under the command of a central government that speaks for the whole and commands its actions on behalf of other nations.

This is the foundation of the European crisis. While the United States had a national geopolitical interest in defending Europe (despite Europe’s failure to create a system under which it could protect itself), Europe evaded two fundamental truths. The first is that relations among European nations change as geopolitical realities change. The second is that European nations would have to make fundamental and largely collective decisions on what it means to be European. Is Europe simply a continent containing small, distrustful nations or would its nations come together to form a multinational state, with their common fates linked economically and militarily, overcoming divergent interests? If the latter were true, its economy would rank second in the world, and given its population, it could field a military that would easily deter Russian (or any other) threats.

Europe’s answer to the question was to create the European Union, an economic entity more loosely organized than a single national economy and wholly separate from a military alliance. Europe understands that individual states cannot be major players in an international system, especially as they pursue their own frequently incompatible goals.

We are now at the point where Europe as a whole must decide what it is to be. Inaction is certainly a decision. The Continent must recognize that being European is a meaningless phrase if Europe is merely the name of an inherently vulnerable and unstable geopolitical region. Or it can choose to be a great power itself. History indicates that the most likely result is that Europe will continue as it is, becoming one of the most dangerous things a nation can be: rich but weak and vulnerable. This was the choice at the end of World War II, and it is the question Europe has refused to answer ever since. Now that U.S. interests have changed, Europe faces the crisis it has tried to evade for the past 80 years.

I suspect that the Europeans will deny that there is a crisis or, in acknowledging it, insist there is nothing to be done about it. For the United States, which has fought in two European wars and has stood guard in the Cold War, disengagement from Europe is imperative – and yet, given the importance of the Atlantic Ocean, the need for the United States to reengage in the future is possible. At the same time, disengagement now could force the Europeans to do something unlikely: rationalize their own situation by uniting. Even so, Europe must face the fact that alliances are elective affinities. Unified states are far sturdier.