By Jacob L. Shapiro

It has been less than a month since President Vladimir Putin declared a successful end to Russia’s intervention in the Syrian civil war and announced the imminent withdrawal of Russian forces from the country. Not even a fortnight later, Islamist militants conducted a deadly mortar attack against Russian forces in Syria.

The Syrian civil war is not over, and it won’t be anytime soon. The short-term damage to Russia’s public relations campaign is acute. But far more important is whether Russia is getting dragged into its very own Middle Eastern morass, and what this means for the various forces competing for power in Syria.

Russian President Vladimir Putin (L) toasts with Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu at a reception for military servicemen who took part in Syrian campaign at Grand Kremlin Palace on Dec. 28, 2017, in Moscow, Russia. MIKHAIL SVETLOV/Getty Images

Russian President Vladimir Putin (L) toasts with Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu at a reception for military servicemen who took part in Syrian campaign at Grand Kremlin Palace on Dec. 28, 2017, in Moscow, Russia. MIKHAIL SVETLOV/Getty Images

On Jan. 3, Russian business daily Kommersant reported that an Islamist mortar attack on Hmeimim air base on Dec. 31 had knocked out four Su-24 bombers, two SU-35S fighters and a military transport aircraft. Russia’s Defense Ministry disputed the specifics of the Kommersant report but not the attack itself. The ministry said that the base had come under mortar fire from a “mobile militant subversive group” and that two Russian soldiers had been killed in the attack.

At this point, it is hard to know for sure the extent of the damage at Hmeimim. Kommersant is generally a reliable source of information and has little reason to fabricate this story. In addition, at least one Russian war reporter posted photographs on social media purported to show the damaged aircraft, though it is not yet possible to confirm their authenticity. If we accept for a moment that the reports are true, it was a highly destructive attack. We don’t know how many aircraft Russia has stationed at Hmeimim currently, but at the height of Russia’s Syria intervention in 2016, it had about 70 aircraft and 4,000 personnel at the base. Recently, Russia’s defense minister said 36 aircraft had returned to permanent bases in Russia. If Kommersant’s reporting is correct, that would mean at least 20 percent of Russia’s air assets at the base – and half of its SU-35S fighters stationed there – were damaged.

The extent of the damage is important for establishing the degree of the damage done to Russia’s image, but for that information we will have to wait. Either way, we can say for sure that the attack occurred and took Russian forces by surprise. Russia’s Defense Ministry has already announced that Russia will expand the security zone around the base and that Russian troops will now be responsible for its security – not Syrian troops, as had been the case. Whichever version of events – or combination of them – is true, it doesn’t change the fact that this is a major blow to Russia’s carefully crafted image. A few more incidents like this one will make it very difficult for Russia to pretend that its Syria intervention has achieved its goal.

Lost in the focus on this attack are the numerous other military operations Russia has undertaken in Syria just this week. Earlier on Jan. 3, Russia’s Defense Ministry reported that an Mi-24 helicopter crashed near Hama military airfield, killing both pilots. Meanwhile, on the same day, Reuters reported that Russian air assets supported a Syrian army assault on a rebel group just east of Damascus. Putin did not set a date for the withdrawal of Russian forces from Syria when he announced victory last month, and recent activity on the ground hardly suggests that Russia will be pulling the bulk of its forces out anytime soon. If anything, Russia will now have to demonstrate that it can finish a job it said was already done.

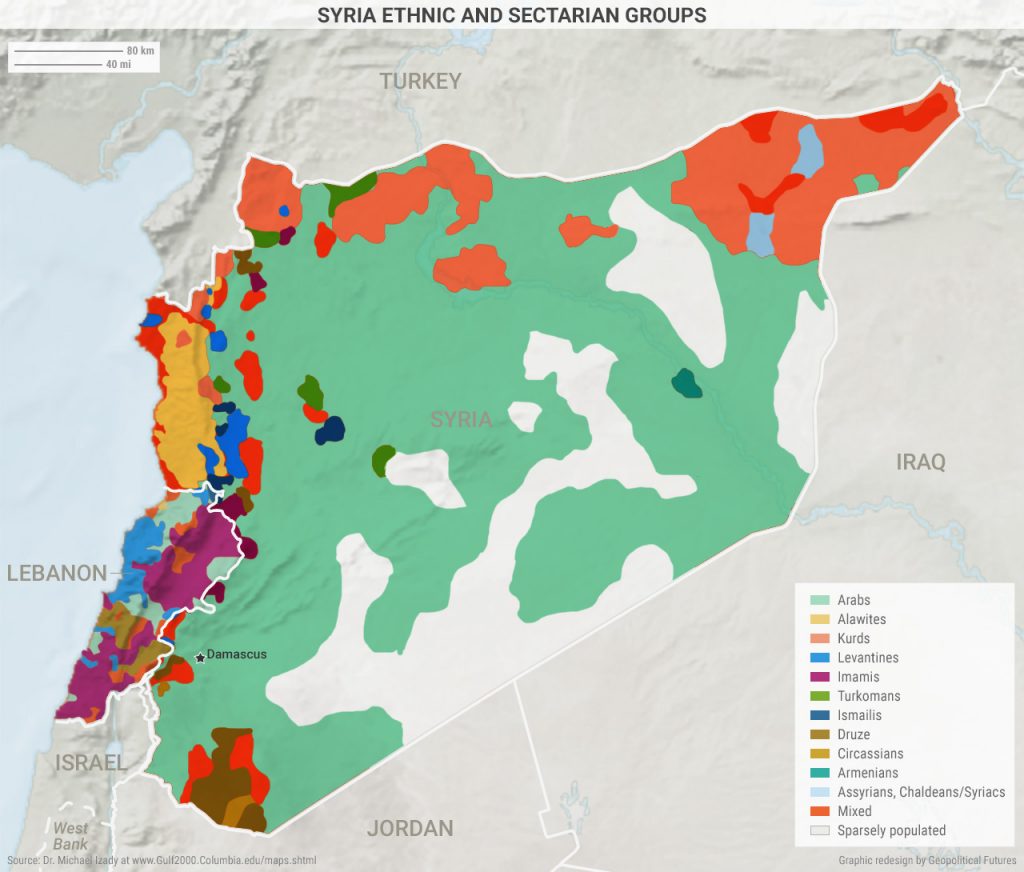

The question now becomes what the future of Syria looks like. Russia has tried to engineer a diplomatic solution that effectively locks in the status quo. At the moment, none of the entities competing for influence in Syria can gain an upper hand. The problem for Russia is that no one, except perhaps the Syrian Kurds, is interested in maintaining the status quo. The status quo does not suit Iran, which wants to see the full restoration of the Bashar Assad regime and Damascus’ resumption of its role as Iranian proxy and linchpin in Iran’s dream to project power to the Mediterranean. It also does not suit Turkey, which just this past week lent its support to the creation of the “National Army,” a 22,000-strong force that will reportedly fight Assad, the Islamic State and the PKK Kurdish militant group but whose first target is to be Syrian Kurds in Afrin. Assad’s regime, for its part, would like to have its country back without having to kowtow to any one power, and that means keeping Russia on the ground in Syria indefinitely to help in its efforts to reconquer the country.

What started in Syria in 2011 was a civil war. That war, in effect, was put on hold when the Islamic State emerged out of the chaos and seized territory in Syria and Iraq. With the Islamic State gone, the civil war has resumed. This is not the narrative that any of the countries involved want the world to hear. Russia and the Assad regime would have the world believe that the only thing left to do is to wipe up a few more pockets of jihadist rebels. Iran would have the world believe the threat is far more serious and justifies an increased Iranian presence. Turkey is still hoping it can somehow put the Syrian Kurds back in their box while replacing Assad with a Sunni-led government friendlier to Turkish interests. Each of these countries is using its own proxies to try to advance its own goals, and each is trying to spin the situation in a way that reflects success.

Success, however, is fleeting in this part of the world. If the Islamic State is defeated and there are just a few rebels left to mop up, how is it that one of Russia’s main bases in the region was shelled with mortars? It would appear there is more work to be done than Russia has let on. That wouldn’t be a problem if Russia hadn’t already attempted to use its Syria intervention as evidence of its power in the region and in the world. But Russia has tried to spin the Syria excursion as a demonstration of Russian power, and that makes this attack, whether or not it damaged the aircraft in question, a distressing omen for Moscow. Russia went into Syria when its economy was in dire straits due to lower than expected oil prices and when Putin’s credibility was suffering after the Ukraine revolution in 2014. The Russian government needs to leave Syria with a victory to bring back to the Russian people. The more remote that possibility appears, the more this intervention has the potential to backfire.