By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Sat Jan. 28, U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke on the phone. The White House said in a statement afterwards that the conversation was a “significant start to improving the relationship between the United States and Russia,” and that the two sides hoped to move forward quickly in tackling “terrorism and other important issues of mutual concern.” The Kremlin’s summary of the phone call (translated by CNN) added that a restoration of mutually beneficial economic ties “could further stimulate progressive and stable development of bilateral relations.” In response, some Republican Senate leaders made the Sunday talk show rounds to demonstrate their opposition to lifting sanctions against Russia.

Geopolitical Futures’ forecast for 2017 is that the U.S. and Russia will “see a superficial thaw in tensions around Syria.” This forecast does not only involve phone conversations between Trump and Putin, nor is it confirmed by the tête-à-tête between the two leaders over the weekend. Rather, this forecast is based on two suppositions. First, the U.S. and Russia have a shared interest in defeating the Islamic State. The two countries have different reasons for desiring this outcome, but the end goal is still the same. Second, the U.S. and Russia have divergent interests when it comes to Eastern Europe. Russia wants to project power into its old borderlands. This is unacceptable from a U.S. perspective.

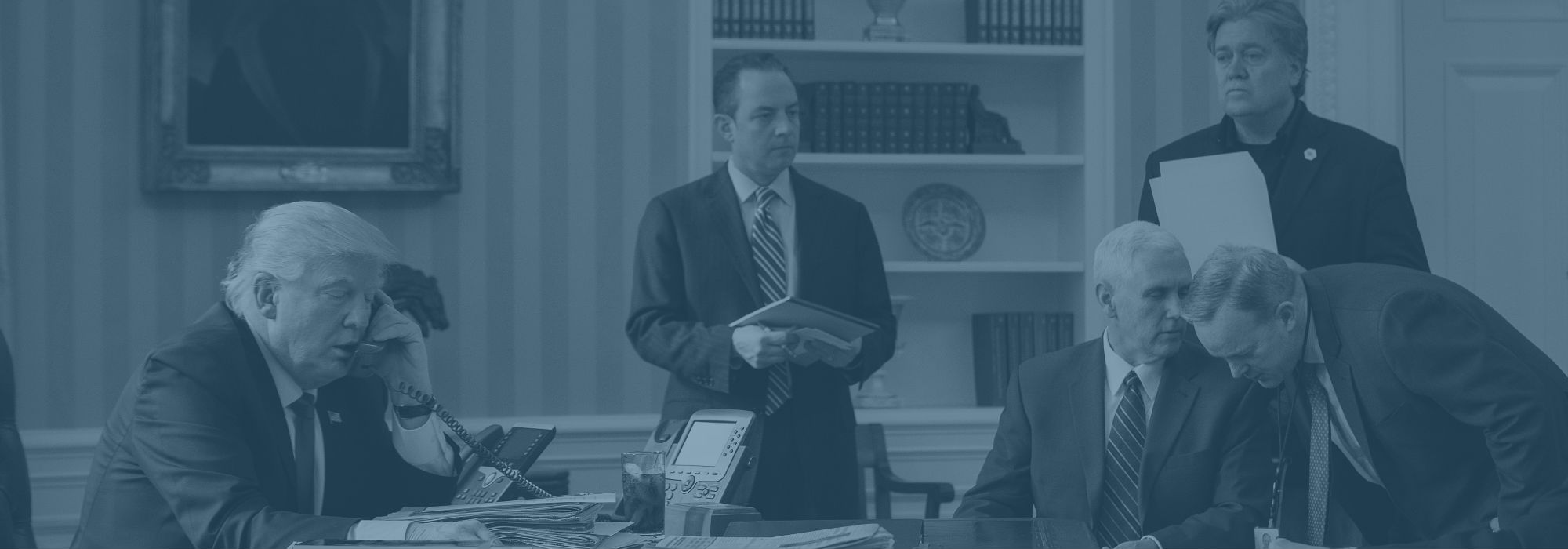

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks on the phone with Russian President Vladimir Putin in the Oval Office of the White House on Jan. 28, 2017 in Washington. Also pictured, from left, White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, Vice President Mike Pence, White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon and Press Secretary Sean Spicer. Drew Angerer/Getty Images

For the U.S., an unchecked IS represents a fundamental challenge to the balance of power in the Middle East. IS is a formidable fighting force that has shown it can bend considerably without breaking – it can respond to challenges by reorganizing its forces in sophisticated counterattacks that hinder its enemies’ attempts to destroy its cherished caliphate. IS is brutal, but many horrible things happen in the world each day; it is the potential strategic challenge IS poses that makes it a threat. For Russia, the issue at this point is preserving Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. IS, not the rebel opposition, is the biggest threat to Assad at this point, and this has been underlined by IS’ recent offensives in Palmyra and Deir al-Zour. Putin has invested significant political capital in demonstrating Russian effectiveness by aiding Assad. Letting IS prevail would be an embarrassment for Russia and would eliminate Russia’s last chess piece in the region.

The Barack Obama administration publicly proclaimed its opinion on the Assad regime’s reprehensibility. By the end of Obama’s term, that stance became something of a liability. The U.S. underestimated IS, and when it became clear that IS was far more than a JV team (as Obama once described it), the administration had to swallow its desire to remove Assad and focus on attacking IS. Trump’s administration has not taken a firm line on Assad, which gives it more flexibility. Trump campaigned on the promise that he was the candidate who best knew how to destroy IS and that the U.S. would do so under his administration. The White House is already reportedly drafting a directive that will instruct Defense Secretary James Mattis to develop a plan to increase U.S. operations against IS and present it to the new president within 30 days. Obama tacitly backed Russian support of Assad; Trump can embrace Moscow’s approach in Syria and present it as an improvement in the relationship with Russia while still achieving his main goal.

It makes sense then for Russia and the U.S. to join forces in opposing IS. This cooperation, however, will be hollow and superficial for two key reasons. The first is that neither the U.S. nor Russia currently have the ability to destroy IS, and joining forces will not increase their chances greatly in the short term. The much-vaunted Russian military intervention in Syria has been endlessly overhyped by most. In the past week, Russia increased airstrikes against Islamic State targets in response to IS offensives. To do so, Moscow dispatched strategic bombers based in Russia to hit targets in Deir al-Zour, Syria, rather than relying on the limited forces it currently maintains on the ground in Syria. The Russian Defense Ministry said earlier this month that it had deployed new combat aircraft to Syria: Four Su-25 jets were added to the Russian air base in Latakia. Various estimates by the International Institute for Strategic Studies and U.S. government officials suggest that before this increase, Russia had perhaps 24 fighters and 12-20 attack helicopters stationed in Syria. That is a small fraction of the Russian air force. It is also not enough of a force to defeat IS. Russian and Syrian forces needed almost a year and a half just to take Aleppo from the rebels, to say nothing of the rebels that continue to operate, albeit at each other’s throats, in Idlib.

The U.S. has even fewer military assets on the ground in Syria. U.S. military technology is the best in the world, but technology can only achieve so much. Defeating IS will require a bloody land campaign to root IS out of its long-held and well-defended strongholds. The U.S. has resisted arming Syrian Kurds for fear of seriously damaging its relationship with Turkey. Trump may revisit this position – he spoke glowingly of Syrian Kurds on the campaign trail – but as he studies this option, two things will become apparent. First, the U.S.’ most important strategic relationship in the Middle East is with Turkey, and such a step will have consequences for Turkish-U.S. relations. Second, the Syrian Kurds have a limited number of fighters – the best estimates come from Syrian Kurdish spokesmen who suggest that the main Syrian Kurdish militia, the People’s Protection Units, has about 40,000 fighters (although they have an incentive to inflate that figure).

This number is lower than the Iraqi forces currently attempting to conquer Mosul against an unknown but small number of IS fighters, a battle that has bled on for months now and is far from over. The Syrian Kurds are also distrusted by local populations in the predominantly Sunni Arab regions in which they are attempting to advance. Meanwhile, the Assad regime has its hands full, trying to maintain its recent gains; it has not shown an ability to defend its territory from IS and has been fighting for years now. It is not about to form an effective attack force against IS. Turkey is reluctant to engage further in Syria at this point and has domestic issues of its own, especially in the wake of last year’s failed coup. Unless Mattis proposes a significant influx of U.S. soldiers on the ground in Syria, it remains unclear which force will do the hard work of beating IS in battle. All the wanting in the world is not going to destroy IS, and there remains a lack of clarity over who is going to make the decisive march on Raqqa.

The second reason cooperation between the U.S. and Russia will be superficial is that as much as the U.S. and Russia may want to cripple IS, they do not share the same goals in Eastern Europe, particularly in Ukraine. GPF’s forecast for Ukraine in 2017 foresees a formalization of the frozen conflict that already exists, but this formalization should not be considered a meaningful step forward in relations. It will be merely the recognition that neither side can make the other do exactly what it wants. That being the case, the status quo will have to suffice for now. Trump has made many tough statements on NATO. That should not be confused for a policy of abandoning the European Peninsula to Russian hegemony. The U.S. continues to deploy limited forces in the Baltics, Poland and Romania, and it deployed an armored brigade in Poland the week before Trump came into office. Trump is not going to withdraw those forces or stop backing a pro-Western government in Kiev just because he has polite phone calls with Putin.

The U.S. and Russia have a shared problem in IS. They are going to cooperate more in addressing that problem, and if the reaction to a simple inconsequential phone call between the two leaders is any indication, this cooperation will be greeted with opinions from all sides of the political spectrum. As this unfolds, it will be important to keep two things in mind. First, the U.S. and Russia cooperating over Syria looks a lot like the U.S. and Russia “not cooperating” over Syria. Not much will change, and both countries will continue carrying out airstrikes against IS targets that prevent IS from expanding but do relatively little to weaken the IS overall. Second, limited cooperation in Syria does not mean broad cooperation in all affairs. The two countries only share an enemy in Syria, but in other areas they have competing interests. The fundamentals of the U.S.-Russia relationship will be increasingly obscured, but that makes them no less real.