When nations negotiate, a quiet settles in before the threats begin. Such is the case now between the U.S. and Russia, which will soon hold talks over the status of Ukraine and any number of other issues. Moscow has published its list of demands – more of a wish list, really – to try to set the agenda. But in the end, agendas are set by reality. A quick recap of Russia’s year is a good place to begin establishing that reality.

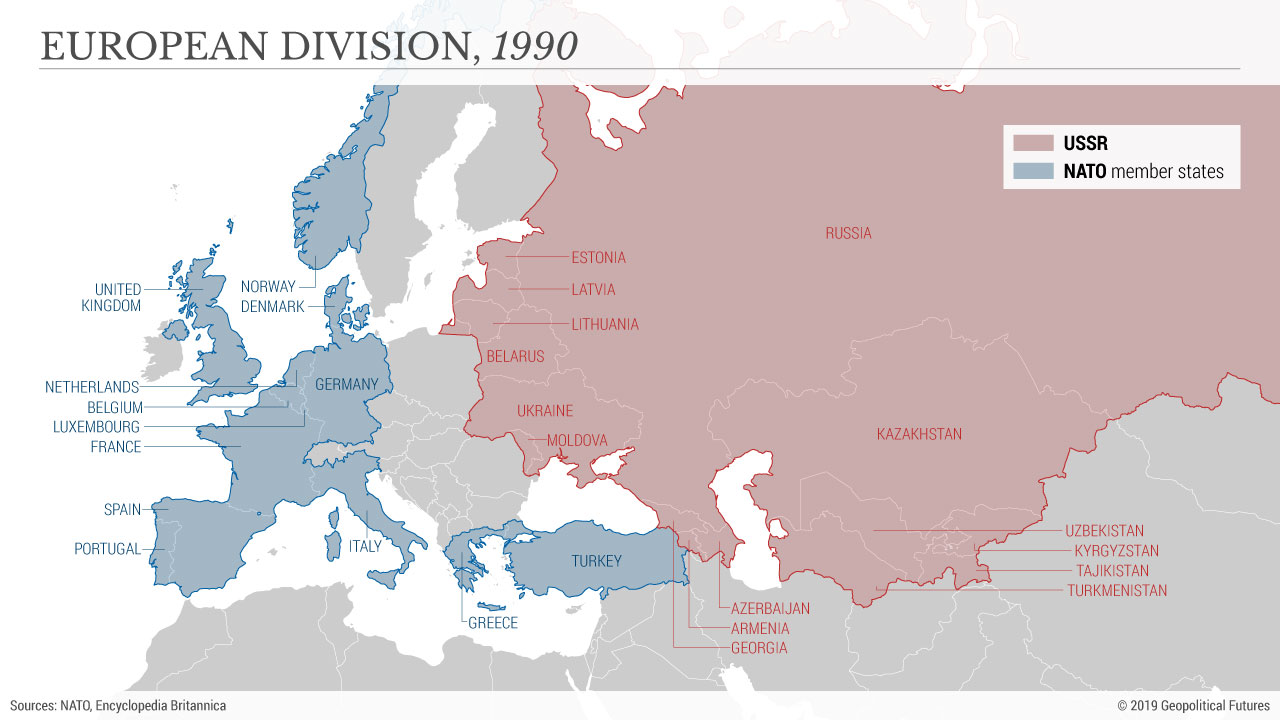

Russia has been trying to reclaim the buffers it lost after the collapse of the Soviet Union. These buffers, the most important of which are in Eastern Europe, insulate Russia from potential attack. In the past, these attacks have tended to emerge unexpectedly, so Russia wants to have them before a threat emerges. It doesn’t necessarily need the buffers to be part of the Russian Federation; it just needs to make sure they are not hostile (or occupied by hostile powers).

Thus, Russian activities in the past year were predictable. When war broke out in the South Caucasus between Azerbaijan and Armenia, Russia dispatched a peacekeeping force and, with its enormous influence in the region, constructed a system of relationships dominated by Russia. In Central Asia, Moscow built a network of airfields, a process that only accelerated as the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan. In Belarus, Russia completely dominates Alexander Lukashenko’s government.

These were important steps for Russia’s reclamation of its buffers, but none of them are as important as Ukraine. Its sheer size allows an enemy force to maneuver, and that maneuverability forces a defender to disperse forces. In war, Ukraine gives Russia time. It spent the year – and really years before it – focused on this moment.

Moscow understood from the beginning that it had to reach an accommodation with Washington. It also understood that the United States, like all countries, comes to the table only when it has to. Washington has been content with the structure of the former Soviet Union. Russia has not. So Russia had to put American interests in the region, particularly in Ukraine, at risk.

The very obvious massing of Russian forces around the Ukrainian border was the logical next step. Deployed as they were, the massed armored forces appeared to be in a position to rapidly overrun Ukraine. The problem, of course, was that though a country as large as Ukraine could be overrun, it could not be overrun rapidly.

Militarily, the United States is in a militarily difficult position. It has no significant force in Ukraine, and any infusion of forces could lead to a long and potentially indecisive war. NATO has no stomach for this kind of confrontation on its doorstep. Apart from limited militaries, the NATO model has morphed into the EU model, and the EU model has morphed into a model whose motto is peace and prosperity. A rapid deployment with few casualties is possible, but the kind of battle Russia offered is of no interest to the EU model, save for a few countries, most notably Poland. The Russian calculation was that the U.S. would not act, and if it did, it would split the Europeans. NATO would exercise and plan in Brussels, but ultra-caution would limit collective action.

From the American point of view, there is no short-term interest in intervening in Ukraine, let alone fighting another potentially losing war at long distance with questionable allies. But there is a long-term danger. The American strategy in the Cold War was to prevent Russia from imposing hegemony over Europe. Such a hegemony would wed Russian resources and manpower to European technology and manufacturing, creating a massive superpower that could challenge the U.S. in the Atlantic. This was a long-range threat, but long-range threats had to be dealt with early and cheaply. The Soviet threat was always there, but it was blocked at relatively low cost and was therefore politically acceptable in the West, especially when they were draped in anti-Soviet ideology and the principles of liberal democracy.

The current situation in Ukraine recreates this long-range threat. The Russians view the United States as unpredictably ruthless – it never knows when the U.S. will take action, and its experience in the Cold War showed a U.S. willing to deploy massive force. Russia had to force the United States to limit its presence in Ukraine without risking a dramatic response. It had to demonstrate its power with a not fully credible force to compel a negotiation but not a massive response. And Washington could not go into talks without demonstrating a credible response to the Russian threat. It’s delicate on both sides.

Ultimately, both sides understood the weakness of the Russian strategy relative to the United States. Armored fighting vehicles such as those Russia sent to the Ukrainian border eat an enormous amount of fuel. An armored division in the U.S. military uses about 600,000 gallons of fuel per day when on the move, and Russia is deploying multiple divisions, which would have to be followed by an endless line of refueling vehicles, coming from vast fuel storages. At best, this is complicated. At worst, it’s a prime candidate for a war of attrition as the U.S., weary of Russia’s anti-aircraft capability, fires cruise missiles from afar. (Russia can, of course, shoot some down, but the losses would be huge.)

The Russian decision to carry out multidivisional armored warfare will depend on how confident it is that the U.S. would get involved, how confident Moscow is that the U.S. would choose a winning strategy, how confident it is in its own defensive systems, and how confident it is that it can politically withstand even a temporary defeat. The Russians have not engaged in multidivisional offensives since 1945. They cannot live with the loss of buffers. They cannot live with defeat.

War is filled with vulnerabilities, many of which are discovered at inconvenient times. The price Russia would pay in the event of a failed invasion is significant in terms of domestic politics and international credibility. The price the U.S. would face by a defeat would be less. Its credibility would be hurt, but a geopolitical imperative would not be lost.

The Russians know this far better than I do. So the coming negotiations will break down here and there; Russian forces will be on full alert, but Russia can’t afford a defeat and can’t be certain of victory. In the end, the thing that the Russians will have gained is that they sat down across from the Americans as equals, and the rest of the world will have seen it. There will be consequences to America for conceding the point, and the Europeans will proclaim the end of American power for the hundredth time. And history will go on.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East