By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Jan. 29, 2002, U.S. President George W. Bush gave his second State of the Union address. It was arguably the most important speech of Bush’s presidency, as he used it to lay out a major change in U.S. foreign policy. Bush identified Iran, Iraq and North Korea as constituting an “axis of evil” because of their pursuit of nuclear weapons and therefore the primary targets in Bush’s “war on terror.” Sixteen years later, all three countries remain significant problems for the United States, so much so that President Donald Trump talked about all three in his first State of the Union address on Jan. 30. But only one of the original “axis of evil” countries is openly and brazenly continuing to pursue a nuclear weapons program: North Korea.

Trump has been consistently contradictory in his public stance toward North Korea. He has threatened North Korea with “fire and fury,” and yet he has signaled his willingness to talk directly with leader Kim Jong Un if it would help bring about a resolution. An argument can be made that Trump’s inconsistency is strategic. If the U.S. is planning even a limited strike against North Korea, his inconsistency may well be a way of luring North Korea’s defenses into complacency. An equally good argument can be made that Trump’s inconsistency reflects his administration’s internal divisions. There have, after all, been a number of reports about internal disagreements within Trump’s Cabinet about the best way to proceed on North Korea, with the national security adviser thought to favor a strike and the secretaries of defense and state opposed.

Trump’s State of the Union address did nothing to clear up the situation. The speech itself was almost conciliatory. Though Trump talked about the “depraved character” of the North Korean regime by pointing to Pyongyang’s role in the death of U.S. student Otto Warmbier last year, he did not present much new policy, despite leaks beforehand to the contrary. In fact, all Trump said was that North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear missiles could soon threaten the U.S., and that the U.S. was “waging a campaign of maximum pressure to prevent that from happening.” A threat of pressure, even maximum pressure, is not enough to make Pyongyang think twice about its nuclear ambitions.

Another development, potentially even more significant, preceded Trump’s speech. Earlier that day, The Washington Post reported that the White House decided last weekend that it would not nominate Victor Cha as the new U.S. ambassador to South Korea, despite the fact that Cha had passed all necessary background checks and had been approved in principle by the South Korean government. While that by itself is not so strange, the reason for the abrupt change of heart was reportedly a conversation in December in which Cha expressed opposition to a potential U.S. strike on North Korea, as well as to U.S. threats to abrogate the 2007 U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement. (A second round of talks aimed at amending, not abrogating, the deal began Jan. 31.) An opinion piece penned by Cha also appeared in The Washington Post the same day as the leak, clearly delineating his problems with a pre-emptive strike.

Reading Between the Lines

The withdrawal of Cha’s nomination can be read in more than one way. On one hand, Cha opposes a U.S. policy that would seek to deter Kim Jong Un with a limited military strike. From Cha’s point of view, such a strike would fail to knock out either Kim’s regime or the nuclear weapons program. His expression of concern might signal just how seriously the administration is considering moving forward with such a plan, as Cha wanted no part of it. On the other hand, withdrawing Cha’s name is perhaps yet another Trump administration bluff designed to unnerve North Korea, a subtle threat meant to make North Korea think an attack is in the offing even if the administration has no intention of going forward with a strike.

As if all of this isn’t confusing enough, there are still more statements and developments to parse. The day before Trump’s State of the Union address, the vice chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff told reporters that while North Korea had made some strides toward acquiring intercontinental ballistic missiles, Pyongyang still has not demonstrated the technological capability to strike the U.S. with its missile program. The same day, the director of the CIA told BBC in an interview that North Korea is “a handful of months” away from achieving that capability – he also said the same thing at a national security forum in Washington in October. In other words, parsing the various statements coming from senior U.S. officials amounts to little more than a hill of beans in determining what the U.S. intends to do.

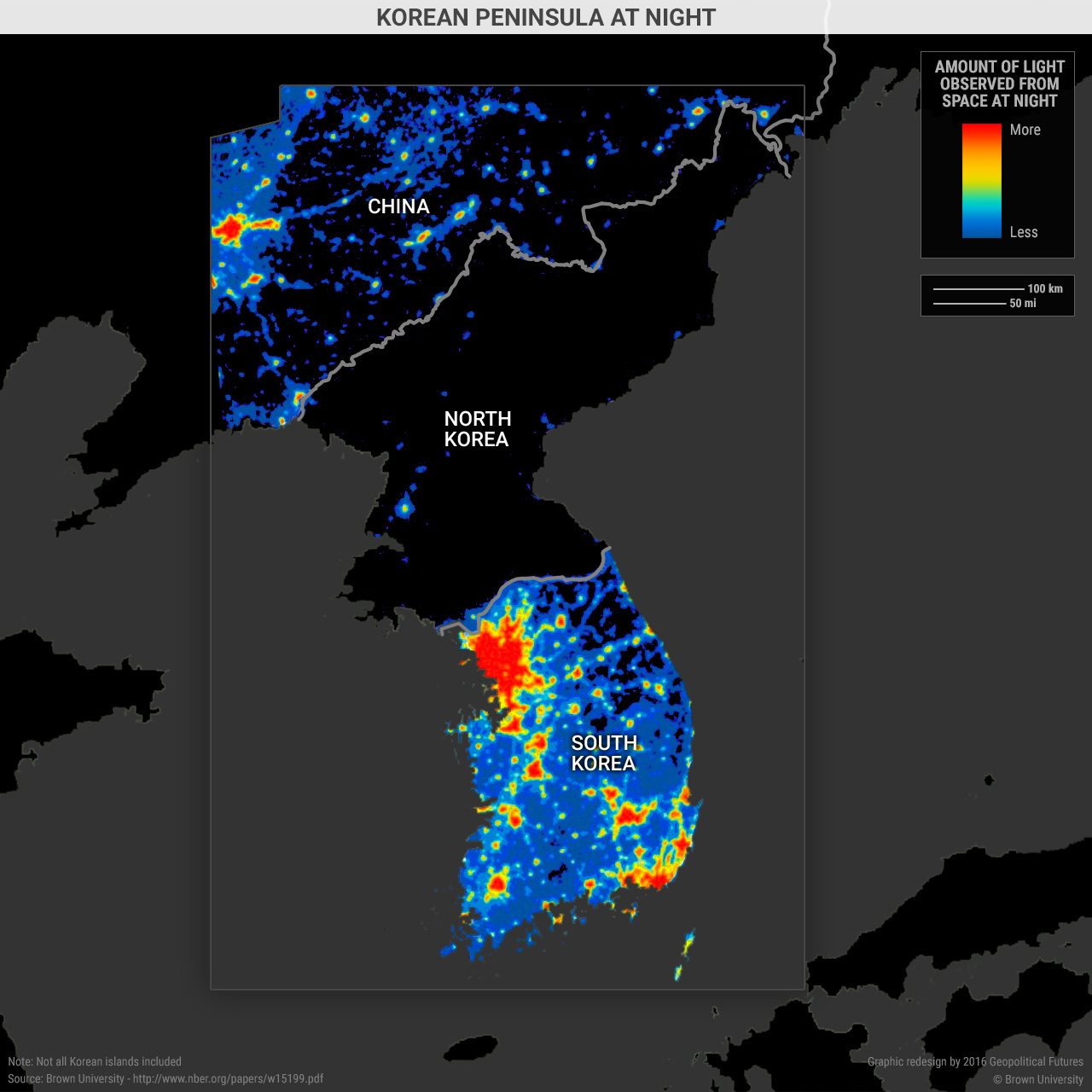

Meanwhile, on the Korean Peninsula, developments continue at their own pace. Russia issued its latest objection to the current U.S. policy of applying “maximum pressure” on Pyongyang. Russia’s ambassador to North Korea told RIA Novosti in an interview that Russia “can’t lower deliveries” of oil to North Korea any further, despite the U.S. imposing new sanctions on North Korea last week. The envoy explained that doing so would create such serious humanitarian problems in North Korea that it would result in a North Korean declaration of war. Both Russia and China have eased the sanctions pressure on Pyongyang by continuing to maintain political and economic ties with North Korea despite U.S. exhortations to apply more pressure.

The North-South negotiation track continues to produce inconclusive results. The start of the 2018 Winter Olympics is fast approaching on Feb. 9, and North Korea is still set to send its athletes to compete at the games, Asia’s latest example of a major sports event being used as a diplomatic exchange. But it remains unclear whether the exchange is actually accomplishing anything. On Jan. 30, South Korea insisted its athletes would participate in a joint training session at a North Korean ski resort (yes, they exist) this week, and a unified North and South Korean women’s hockey team will compete at the games. Then, on Jan. 31, North Korea abruptly canceled a joint cultural performance with South Korean artists set for Feb. 4, which Seoul immediately deemed “unilateral” and “very regrettable.” The ostensible reason was North Korea’s frustration with South Korean media reports it felt were biased.

Missile Crisis as Charade

The North Korean missile crisis has reached the level of a farce. The U.S. continues threatening, South Korea continues objecting, Japan continues to lose confidence in the U.S., China continues to use the situation to split off South Korea from the U.S. alliance, Russia continues to interfere to keep the U.S. distracted on the Korean Peninsula, and North Korea continues its pursuit of nuclear weapons. The only thing that has truly changed in the last two months is that now Seoul and Pyongyang are engaged in intense talks over the finer points of women’s figure skating and cultural exchanges.

The U.S. has a choice to make. Conduct a limited strike that could set the North Korean nuclear program back – a move that risks breaking the U.S.-South Korea alliance – or accept a nuclear North Korea and the attendant risks it poses to the U.S., while building a more robust North Korea containment strategy. Both come with pros and cons, and all things being equal, we expect the latter, but decisions as tactical as this depend less on geopolitics and more on the information to which the ultimate decision-makers have access. The only thing that can be said for certain at this point is that the U.S. hasn’t yet made up its mind.