By Jacob L. Shapiro

Of all the parties involved in the Korean missile crisis, the most difficult to read is China. The Chinese Foreign Ministry’s almost daily platitudes about the need for a peaceful resolution do little to reveal what China’s real interests and objectives are – and what they are is multiple and conflicting. At one level, China is concerned with the balance of power on the Korean Peninsula. China doesn’t want Pyongyang to have nuclear weapons, and it doesn’t want the peninsula to unify. But at the same time, what happens on the Korean Peninsula also affects China’s relationship with the U.S., and despite the deep economic ties between the two countries, from Beijing’s perspective that is a relationship defined ultimately by fear and mistrust.

Roots of Mistrust

To understand where this mistrust comes from, we need to revisit some history. When North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, it did so without Chinese participation. What assistance China did offer before the invasion was rebuffed by Kim Il Sung’s young regime, confident as it was that it would not only succeed in its attack but that the invasion would provoke a popular uprising in South Korea as well. North Korea’s invasion caught the U.S. flat-footed. In its panicked analysis of what had happened, the U.S. feared that the invasion might be part of a much larger attack by the communist bloc against U.S. interests. That is why two days later, then-U.S. President Harry Truman ordered the 7th Fleet into the Taiwan Strait.

At the time of Truman’s order, the People’s Republic of China was less than a year old. It was led by Mao Zedong, who was deeply suspicious of U.S. intentions toward his regime. Mao’s concerns were not unfounded. Mao remembered what happened after World War I, when, upon arrival at Versailles, Chinese delegates discovered that the U.S. had recognized a Japanese claim over Chinese territory that European powers had once held. Mao also lived through the United States’ breaking off support for the Chinese Communists – after the U.S. had supported them in their fight against Japan in World War II – because of the Cold War. The U.S. instead poured its resources into rebuilding Japan, which had invaded and brutally occupied China during the war. In addition, the U.S. threw its support behind Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalists in the hopes that they would defeat the upstart Communist forces. (The term “Chinese nationalists” has always been something of a misnomer – the Communists were just as nationalistic as Chiang’s forces, but that is what history has come to call them.)

Moving the 7th Fleet into the Taiwan Strait was the last straw for Mao. To him, the U.S. was the only thing standing between his Communist Party of China and the creation of a unified Chinese nation-state beholden to no one but the Chinese people themselves. But China could do nothing to avenge the slight directly. It didn’t have the military force necessary to conquer Taiwan with the 7th Fleet standing guard. The only place China could hope to respond was in North Korea, where the rugged geography negated some of the advantages of the United States’ technological and military superiority. China entered the Korean War in October 1950, and because of China’s intervention, the Korean War ended in a stalemate that remains unresolved to this day.

Cycles of History

Fast forward to today, and it is plain to see that the more things change, the more they stay the same. Korea is still divided, and despite momentous growth in the economy and the military capabilities of the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan remains outside of its control. But it’s not just the strategic reality that is the same. It’s also true that for China, the North Korea and the Taiwan issue are inextricably linked.

On Dec. 2, soon after the U.S. presidential election, President-elect Donald Trump did something that no U.S. president had done for more than 37 years: He had direct contact with the president of Taiwan. It may seem a small thing, but for Beijing, this was not a trivial moment. It took Trump another two months to accept the “One China” policy – two months where Chinese strategic planners were left to wonder what the United States’ true intentions were with regard to Taiwan, and China’s territorial integrity in general.

Chinese vendors sell North Korean and Chinese flags on the boardwalk next to the Yalu River in the border city of Dandong, northern China, across from the city of Sinuiju, North Korea, on May 24, 2017. KEVIN FRAYER/Getty Images

Chinese vendors sell North Korean and Chinese flags on the boardwalk next to the Yalu River in the border city of Dandong, northern China, across from the city of Sinuiju, North Korea, on May 24, 2017. KEVIN FRAYER/Getty Images

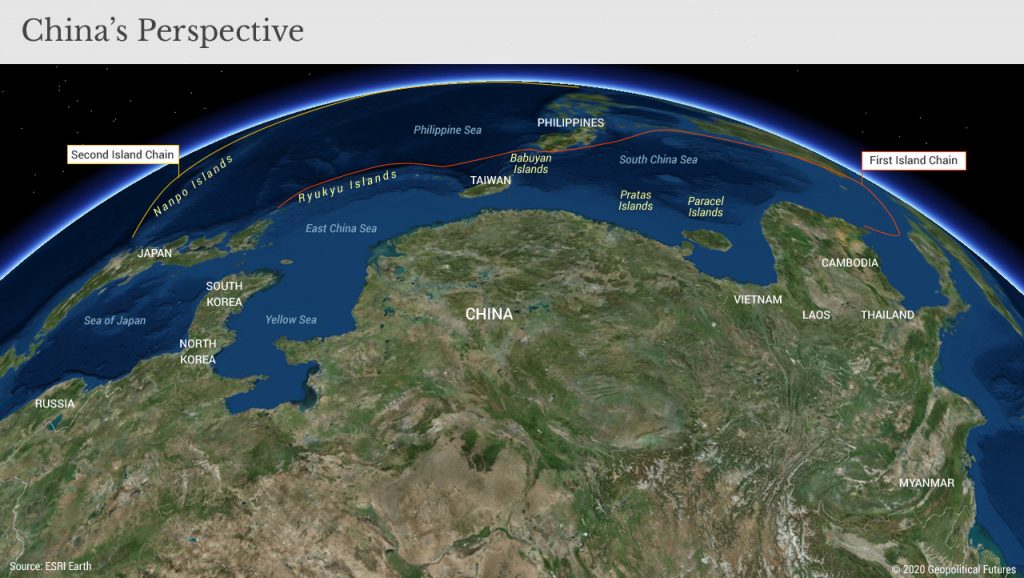

From the perspective of the Communist Party of China’s political legitimacy, Taiwan is the only part of China it has been unable to capture and integrate into its revolution. From the perspective of China’s defense strategy, Taiwan is an island 100 miles (160 kilometers) away from the mainland that a powerful navy could use as a base from which to blockade China or even to attack the mainland. If Taiwan were to gain U.S. recognition and perhaps even host U.S. forces, what is already a Chinese handicap would become an existential threat. It would also make a mockery of China’s faux-aggressiveness in the South China Sea, and would make previous American freedom of navigation operations look friendly in comparison.

China also faced another potential threat from the Trump administration: the potential that the U.S. might block Chinese exports from the U.S. market. A trade conflict between the two sides would hurt both parties, but China was always going to be hurt more, and President Xi Jinping could not afford an economic crisis in the lead-up to this month’s Party Congress, where he will solidify his dictatorship over the country.

What China needed, then, was a bargaining chip, a way of turning its position of weakness into one of strength. Enter North Korea. China had to proceed carefully. On the one hand, China had to appear to have enough control over Pyongyang to divert the Trump administration from following through on some of its threats to redefine the U.S.-China economic relationship. On the other hand, China could not overstate its influence in North Korea such that the U.S. could hold China directly accountable for failure to help denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. The July 2017 revelation by China’s Ministry of Defense that contact between the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and North Korea’s military forces has completely ceased in recent years was meant to underline the limits of what Trump’s bargain with Xi at Mar-a-Lago in April had bought.

In reality, Xi has as little control over Kim Jong Un’s actions as Mao had over Kim Il Sung’s. But Xi does not need total control over Kim’s regime to use Kim to China’s advantage; all he needs is for China and North Korea to share an interest in limiting U.S. power in Asia, and there is little to suggest that interest is going away anytime soon. North Korea is pursuing a nuclear weapons programs to establish a nuclear deterrent against the United States. China doesn’t have to make such moves. It already has nuclear weapons and is far more powerful than Pyongyang. That allows China to be more pragmatic – that is, cooperative – in its dealings with the United States. But China’s pragmatism and willingness to work with the U.S. should not obscure the fact that, like North Korea, China is deeply suspicious of U.S. motives.

This, in turn, is one of the major limiting factors on the U.S. ability to attack North Korea. China has a mutual defense treaty with North Korea. And China, though it would prefer the status quo on the Korean Peninsula, does not necessarily lose if the U.S. were to try to solve the North Korea issue by force. This is because the attempt, absent some unknown technological devilry, wouldn’t work. The U.S. has tried and failed twice to win a war on the Asian mainland, and the situation in Korea hasn’t improved enough to think that the third time would be any different. China can’t beat the U.S. at sea, and it can’t take back Taiwan, but it can beat the U.S. in North Korea. That allows China to remind the U.S. that, though Beijing may not yet be able to achieve One China, its memory is long, its patience is vast, and classes in Confucian humility are readily available to those who seek them out.