By Antonia Colibasanu

NATO heads of state met to inaugurate the alliance’s new headquarters in Brussels on May 25, and the two main topics of conversation were defense spending and the alliance’s role in fighting terrorism. Both issues indicate that NATO is increasing its political role while diminishing its military function.

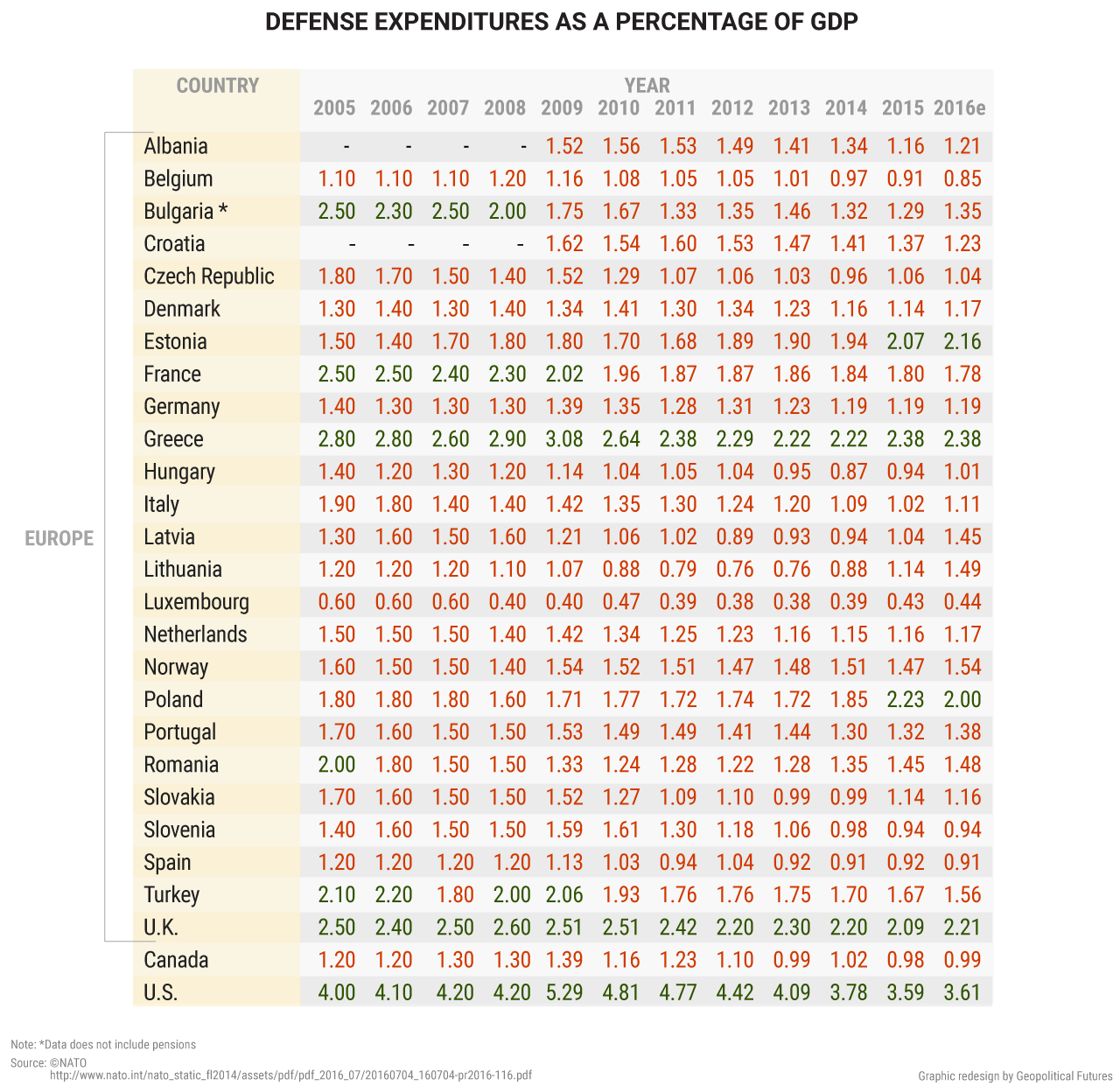

The alliance’s link to the national interests of its member states is breaking, meaning that discussions on strategy rarely take place within the alliance. Its military function is declining because alliance members no longer share a common interest as they once did. This is evident from the way member states decide to buy new equipment and prioritize defense spending. In an ideal world, the U.S. would like Europe’s collective military capability to equal at least 50 percent of U.S. military capability. Washington would argue that it is unfair for the U.S. to account for more than 70 percent of NATO members’ defense spending while its gross domestic product is only 48 percent of their combined GDP.

NATO heads of states arrive for the unveiling ceremony of the Berlin Wall monument, during the NATO summit at the NATO headquarters, in Brussels, on May 25, 2017. MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images

U.S. President Donald Trump has talked about his desire to see Europe increase its contributions and capabilities. The Europeans, on the other hand, have suggested that the fact that they spend less on defense should not be interpreted as contributing less to the alliance. Each side has presented the issue in its own way, focusing on how these statements will play at home. NATO has moved its headquarters into a new building in Brussels and that, along with these disagreements, seems to signal that it is shifting from being a primarily military alliance to a more political one.

Consensus Isn’t Possible

NATO won’t easily come to an agreement on defense spending because each country faces a different geopolitical reality and therefore has different needs when it comes to defense. They may be able to settle on broad political statements but not on specific plans. Portugal has different national interests than Romania – and not only will they disagree on the amount of money that they should be spending on defense, but they will also have varying military priorities and views on how to spend it.

The alliance was created during the Cold War, when members shared an interest: protecting Western Europe from the Soviet threat. Now, the alliance no longer has a common enemy, and so coming to an agreement on things like what military equipment and weapons are needed is impossible. These countries all face different levels of threats, which explains why defense spending varies from state to state – some members just don’t see defense as a priority.

The lack of consensus is also apparent when it comes to the alliance’s counterterrorism efforts. During their meeting in Brussels, NATO leaders pledged to “do more to fight terrorism,” which might seem like a promising sign. But members have made this commitment and failed to live up to it many times. After the 9/11 attacks, the U.S. administration insisted that its NATO allies contribute to the U.S. counterterrorism effort. But France and Germany, along with Russia, opposed the Iraq War. The first Obama administration asked NATO to increase its troop commitments in Afghanistan to help fight the Taliban. But with the exception of the United Kingdom and some Eastern European countries such as Poland, Romania, the Czech Republic and Albania, European allies rejected Obama’s request.

Since 9/11, the U.S. has seen its counterterrorism operations, including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as part of NATO’s collective defense principle – the idea that an attack on one member is an attack on all. Though there are many reasons the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were problematic, Trump’s insistence that NATO members help in the fight against terrorism shouldn’t be a surprise. But the U.S. looks at counterterrorism operations differently than the Europeans do. For the Europeans, their priority is preventing terrorism in Europe, and NATO can do little to prevent terrorist attacks on the Continent.

Security in Brussels – A Case Study for Europe

In no other European city is the perception of the threat from terrorism stronger than in Brussels, not because Brussels has witnessed more terrorist attacks but because of the high presence of military forces. Special operations forces and military personnel are visible in other Western capitals like Paris and Berlin as well. They were deployed after terrorist attacks were carried out in these cities, and even after a state of emergency was lifted, military forces remained deployed in most capitals.

But in many countries, military forces are usually accompanied by domestic security forces. In Brussels, these reinforcements are lacking and the military is virtually the only force ensuring civilian safety. This is because domestic security is weak in Belgium. Some might question the efficiency of fighting terrorism this way, using military forces to patrol civilian areas, but the military presence is used as a deterrent and is intended to prevent another attack from taking place. It is also, however, a constant reminder of the terrorist threat. This is one of the goals of terrorism – to create the fear that an attack can happen at any time and in any place. And it is unclear if the presence of military personnel actually limits or contributes to this fear.

The military’s effectiveness in combating potential terrorist threats in Brussels is also questionable because soldiers carry limited weaponry and are not allowed to go beyond the perimeter to which they’re assigned. If they see a threat outside of their area, they have to call domestic security forces. To make things worse, there is also limited cooperation and intelligence sharing between the military and domestic security forces. In Belgium, there is a lack of confidence in the domestic security forces, and many hope that the military will break these rules and jump to the rescue during an emergency situation.

This tension between the military and domestic security forces is common to all NATO member states. Alliance members share some intelligence between their defense departments, but they don’t share any information at the domestic security level. And it’s likely to stay this way, partly because of member states’ resistance to sharing intelligence at a more advanced level than they do now and partly because adding another layer of decision-making might actually slow things down. Fighting terrorism at home has become the top security priority for most NATO members and is more efficiently done at the national level.

NATO can do little to help improve security in Brussels or elsewhere in Europe. But it can issue a press release saying it wants to do more to fight terrorism. Such claims have been made before. NATO places terrorism in the same category of threats as propaganda and cyberwarfare, and it has established research centers to study these so-called hybrid threats. It has also discussed joining EU forces in combating these new challenges. But this will amount to little more than bureaucrats holding meetings, while little is done to actually prevent more attacks.

Bureaucrats at NATO as well as the EU know the reality. They complain about the restrictions they face and the lack of action from politicians. But politicians have their own limitations – most importantly, their electorates. Above all, NATO leaders don’t want to admit that the alliance is ineffective and would rather NATO remain in its current hopeless state. So would the bureaucrats who work there, since their jobs depend on it. This might seem like an absurd situation, but in politics, absurdity is a substitute for dealing with a reality that can cause great damage if it is acknowledged.