By Jacob L. Shapiro

In 2007, Japan, South Korea and China decided that their foreign ministers should hold a summit once a year. Since then, they have met each year except 2013 and 2014. The most recent meeting was Aug. 24, in the Japanese city of Kurashiki. This year, the Chinese and Japanese officials held a separate bilateral meeting as well. One of Japan’s major national newspapers, the Yomiuri Shimbun, led its coverage of the meeting with the headline: “Tense Japan-China Relationship Expected to Continue.” Another of Japan’s major papers, the Asahi Shimbun, instead led with a different headline: “Japan, China Agree on Need to Avoid Clashes on Senkaku Issue.” So, which is it? Are tensions between Japan and China increasing, or have both sides agreed to take a step forward in resolving a sore spot?

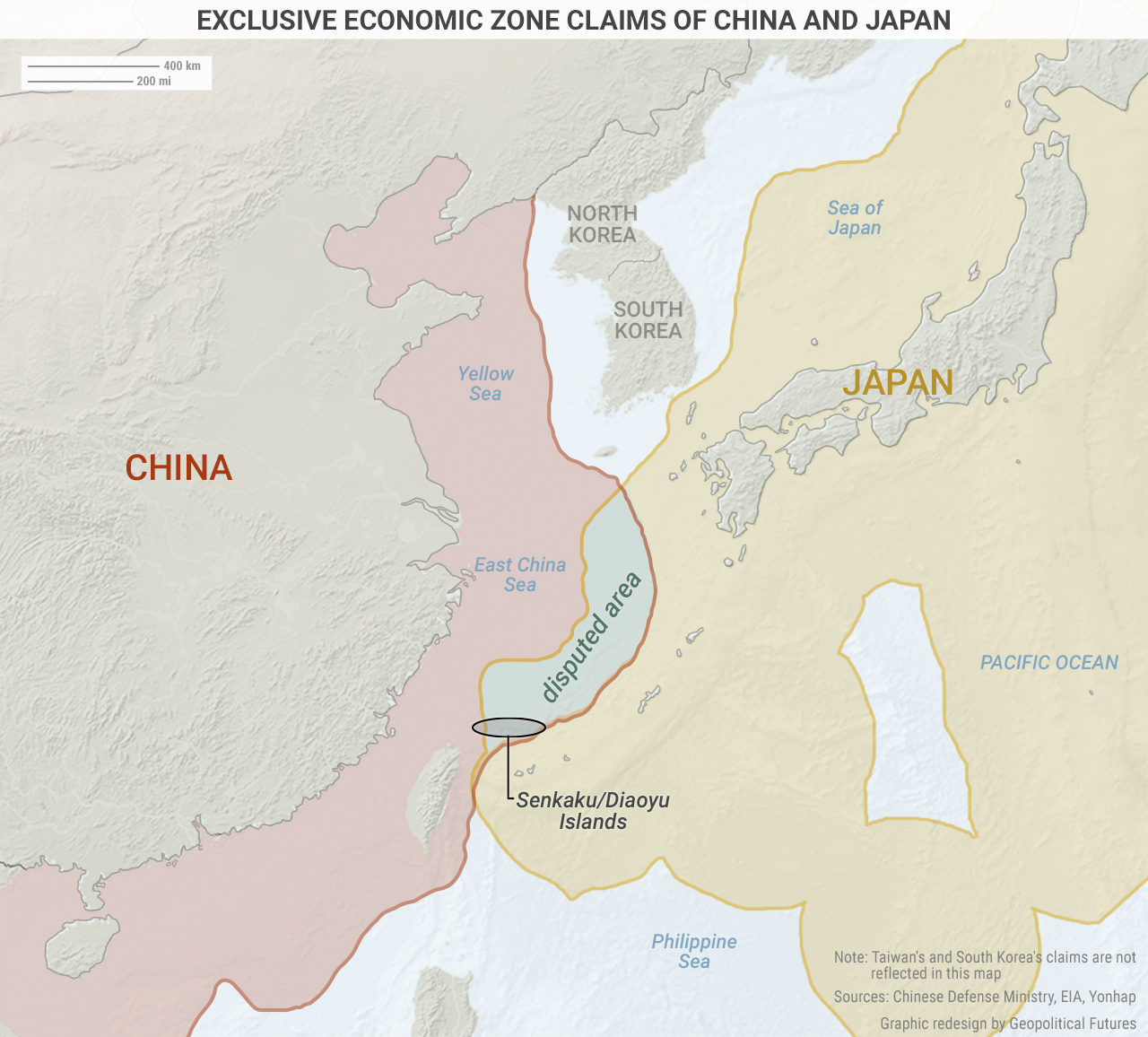

The surface level answer is that of course tensions are rising. There has been no shortage of threats and minor actions between Beijing and Tokyo this year. Last Saturday, a story appeared in Japanese media that China had warned Japan about dispatching the Japan Self-Defense Forces to the South China Sea for joint freedom of navigation operations with the U.S. Navy. China said doing so would cross a “red line.” Earlier this month, hundreds of Chinese fishing vessels were accompanied by various Chinese coast guard vessels as they entered territory disputed with Japan as parts of their Exclusive Economic Zones near the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Those are just two of the most recent events.

The problem with focusing on every minor incident or perceived diplomatic slight in East Asia is that it tends to overinflate the issue. There are many instances that could be described as “raising tensions” in the waters separating China from Japan. At a certain point, however, it becomes unclear just what “raising tensions” means. There have been no shots fired between either side. No one has died, and no declarations of war have been issued. The only country doing any shooting is North Korea, and it is in the North Koreans’ interest to be sure not to hit anyone. It’s also not clear that they could if they tried, but that’s a separate issue.

What did China mean when it said Japan shouldn’t cross a “red line”? Are the Chinese suggesting that they would actually do something? Also, why was this made public in the first place? The Chinese certainly wouldn’t mind such a threat being made public because it fits into their image of becoming a world power capable of defending their strategic interests. The Japanese want China to look aggressive and overbearing so that people will fall in line with Japan’s position rather than China’s.

The catch is that Japan has little interest, if any, in the South China Sea, besides making sure China doesn’t get too dominant – it knows what will upset China and what won’t. That’s why, when the Japanese had military exercises with the U.S. and India in March, they did it in the Philippine Sea and not the South China Sea. This is a careful choreography followed by both sides – you can send a ship to one place if you are upset, and send some fishing boats to another place if you are really upset – and everyone knows what would lead to real fighting. In the end, everyone is careful not to make that move.

On the other hand, Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Communist Party want to encourage all the media interest in the militarization happening around the first and second island chains. Xi is attempting to reinvigorate the ideological legitimacy of the party, but that is going to take time. Xi’s government is also overseeing an economy that is in a moment of extreme transition. The previous promises of unlimited prosperity can no longer be fulfilled. Getting feisty and territorial with China’s biggest rival in the region is for domestic consumption more than anything else – it can help distract from what’s happening in China.

But Xi can’t go too far. Picking a fight with Japan or the United States and then losing would be far worse for the Chinese government than the fact that it is less than honest about the true rate of GDP growth or unemployment in the country. And it would be a fight China could easily lose. Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force is a powerful navy in its own right, to say nothing of the force the U.S. can bring to bear if it feels it necessary.

So there is a tendency to overstate the level of hostility between China and Japan. But completely dismissing the strains on the Sino-Japanese relationship commits the same mistake as overinflating the various meetings and incidents in the East and South China seas. The Sino-Japanese relationship is the center of gravity of East Asia, and together China and Japan represent over 20 percent of the world’s GDP. All the noise about the Senkakus/Diaoyus and whether Xi will consent to visit Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on the sidelines of the G-20 summit in Hangzhou in September may not be very important. What is important is the fact that China’s and Japan’s interests are diverging at some level.

And this in turns goes back to the key dynamic shaping the entire region now: the status of the Chinese economy. China and Japan have a deeply intertwined economic relationship. China is Japan’s second largest export market; Japan is China’s third largest export market. After the Chinese economy took off in the 1980s and began its 30-year run of high growth rates, Japan was one of the main foreign investors in China, pouring over $1 trillion into the Chinese economy. Often the narrative of the deterioration of Sino-Japanese relations goes something like this: after a Chinese fishing trawler crashed with a Japanese coast guard vessel near the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in 2010, Japan got increasingly skeptical of investing in China and began to pull out factories and operations.

In fact, it’s the other way around. The tensions didn’t drive Japanese companies out; the underlying weaknesses of the Chinese economy did. Labor costs began to rise in China, and so Japanese companies looked elsewhere to improve their bottom line. Japanese investment in China peaked in 2012, but has been dropping precipitously ever since. Last year it dropped 25.2 percent, to a total of $3.21 billion, according to China’s Ministry of Commerce. The weakness in the Chinese economy made it less profitable for Japanese companies to operate there, at the same time that it threatened the Communist Party’s legitimacy in China. That, in turn, led China to start beating its chest more in its near abroad. The economic relationship with Japan was still important, but the stability of the party’s rule was more so, and there wasn’t anything China could do to get the investment back anyway.

Ultimately, both sides continue to have many interests in common. Besides the linkages in the two economies, both China and Japan derive a substantial portion of their economy from exports (China more so these days, but Japan still does as well). Both also rely on imports, especially of various raw materials (Japan more so than China in this case). That means that both China and Japan are dependent on free navigation of the sea lanes that make these imports and exports possible. As long as the United States is guaranteeing that, and as long as both sides are only pushing the envelope at mutually understood levels, these moves will all belong to the realm of gesture more than anything else. That can change, of course, but we don’t expect it to any time soon.

The day after the trilateral summit in Kurashiki, Japanese National Security Council chief Shotaro Yachi traveled to China and met with the Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi as well as Premier Li Keqiang. It seems the only thing that came out of the meeting was that both sides agreed to consider a meeting between Xi and Abe next month. If Xi and Abe do end up meeting, perhaps they will have a productive conversation and agree upon a certain amount of decorum in their maritime squabbles. Or perhaps they won’t meet, and people will read the tea leaves and suggest that the situation is deteriorating even more. Either way, it won’t change much. Geopolitics drives the Sino-Japanese relationship, and that means more saber rattling and status-quo levels of conflict for the time being.

So have the Chinese and Japanese agreed that certain clashes in particular places should be avoided? Yes, most certainly, there is an understanding there. And yet, aren’t tensions rising? Yes, again, most certainly. Both headlines end up being correct. What I can add is that I hear that with rising tensions in the East China Sea and $1.85 you can buy a cup of coffee at Starbucks these days.